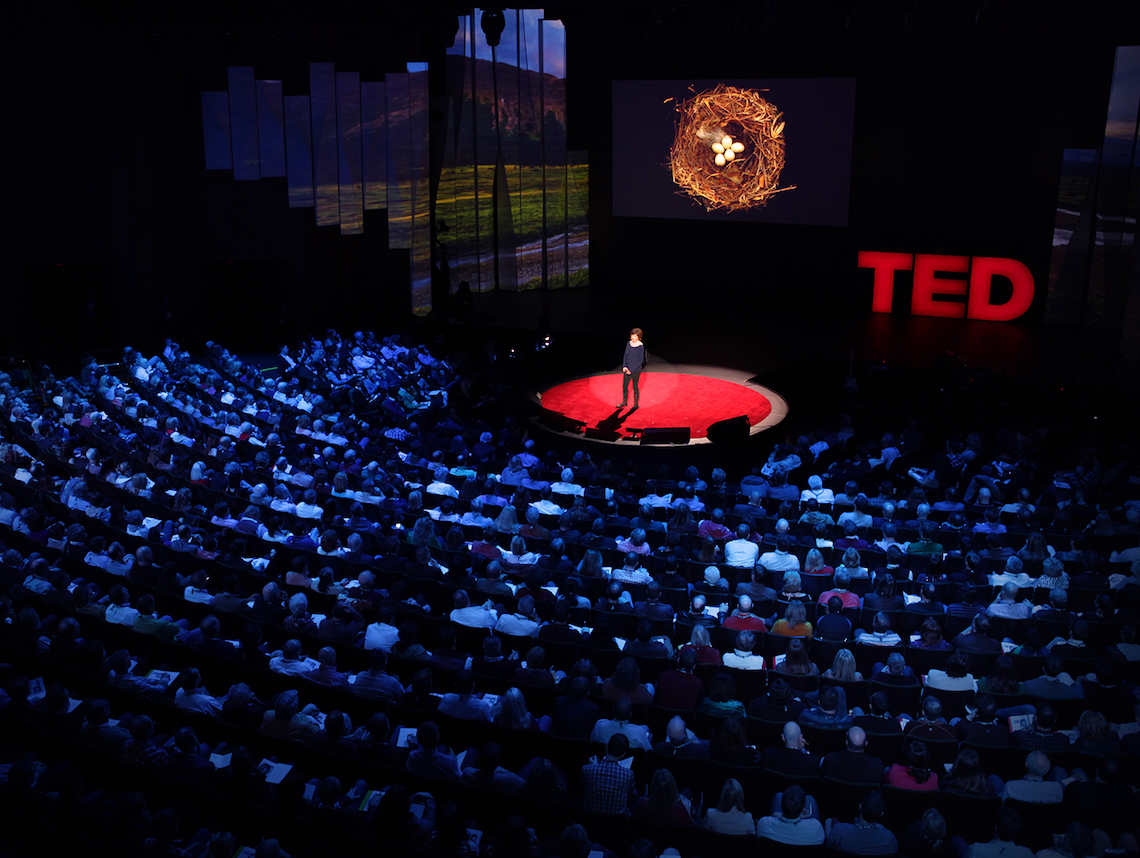

The TED conference has become famous because of the TED Talks broadcast throughout the world, and available online. The talks have beguiled and instructed, with a wide range of topics from the workings of the human mind to the outer reaches of technology to social innovation. For several years, I have attended the conference, but at last month’s annual gathering in Vancouver, B.C., something happened that to me was unprecedented and remarkable.

TED stands for Technology, Entertainment, Design. Some of the most eminent people in the world speak and attend: Bill Gates, Elon Musk, Al Gore, Bono, actors, educators, financiers, scientists, psychologists and so forth. This year, former world chess champion Gary Kasparov spoke about the intersection of human intelligence and technology.

In the eight years I attended TED, with the exception of the curator of the Vatican Museums, I never ran across another member of the clergy — not a priest, minister, imam or rabbi. Despite the many Jews who attend TED who have distinguished themselves in their fields, I never saw another kippah apart from mine. Although I was often approached in a friendly way to answer questions about my religious convictions, people seemed amused or even astonished that a rabbi would be at TED. I always was puzzled at the double-sided neglect: Why weren’t more religious people interested in the remarkable advances that TED showcases, and why wasn’t TED more interested in the power of religion?

Each year, I would talk to people about this question, which troubled me. If religion is to enter the modern world, it cannot ignore the kind of learning and teaching that goes on at TED. And although some at TED are plainly hostile to religion — I’ve had (always amicable) exchanges there with such prominent atheist writers as Sam Harris and Daniel Dennett — I maintained that others would benefit from understanding more about religion. After all, I argued, if you want to change the world, religion is the army with the greatest number of troops on the ground, scattered throughout the world, able to help. When I volunteered a few years ago to help rebuild an orphanage in Haiti, almost everyone else I met there, many of whom had been working in the country for years, were Christian aid workers.

Yet, so far as I could see, since Pastor Rick Warren’s address in 2006, religion had been banished from TED. And then, this year, something remarkable happened.

On the first day of the conference, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, former chief rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of Britain, addressed the attendees. He spoke about identity and otherness, the promise of America, reaching out, welcoming the stranger, acts of goodness and how the Jews managed to maintain their identity by telling their story. It was a message pitched to the TED audience but one that would not have been out of place in a synagogue, except for the omission of overt theological motifs. It also was eloquent and beautifully delivered. When Rabbi Sacks concluded, the hall erupted in a sustained standing ovation.

The following day, we were told a surprise world leader would address us. The rumor swept across TED that former President Barack Obama would appear. When the time came, however, speaking via video transmission was Pope Francis.

The effect was electrifying. Once again, the pope’s message was not unexpected. He, too, spoke about care for others, how technology must be fashioned to serve human ends, and the importance of peace. It is fair to say that neither Rabbi Sacks nor the pope conveyed essentially new information or ideas. Rather, they beautifully packaged old truths.

But as I walked the halls afterward, these were the two speeches everyone was talking about. Amid the technologists and historians and innovators, representatives of these two ancient traditions struck the deepest chord.

As one would expect, the people who attend TED are future oriented. They trust the promise of technology, striding around halls studded with virtual reality booths, next generation car designs and a variety of high-tech displays. Sometimes, however, the seductions of tomorrow blind us to the power of the past.

Suddenly in a hall of visitors sporting jeans, sneakers and mobile devices, we witnessed tradition’s capacity to spark hearts. Data-driven social scientists rose to acknowledge the cogency of telling the Passover story. People who spend their lives working on gene sequencing cheered language about shaping souls. A moment of convergence swept the hall, when technological transformation bowed its head to ancient, shared truth.

The pope asked the people gathered there to use their gifts for the benefit of humanity and to take care not to leave the less fortunate behind. In a gathering of privilege, those words struck a chord; among people who are filled with dynamism and the desire to do good, here was an ancient affirmation that they are valued and needed. And it came from a place that many had long since dismissed.

This year, the modern world of Silicon Valley briefly clasped hands with ancient Jerusalem. The wired world was strikingly rewired: TED took the bold step of demonstrating that the wisdom of tradition has much to add to the power of innovation.

David Wolpe is the Max Webb Senior Rabbi at Sinai Temple. His most recent book is “David: The Divided Heart” (Yale University Press).

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.