“There was a time when writers cared more about the truth than their status; when reason and respectful debate were privileged over trendy ideology and virtue signaling; when critical thinking and analysis were honored more than branding and ‘influencers.’”

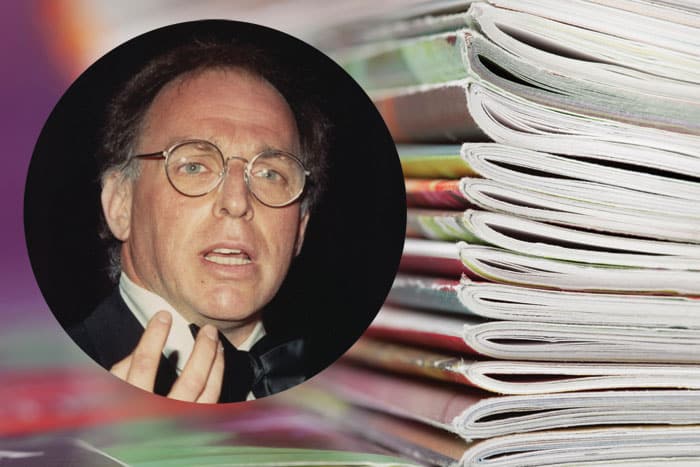

This is how Karen Lehrman Bloch begins her cover story this week on the irrepressible Martin Peretz’s new memoir: “The Controversialist: Arguments with Everyone, Left Right and Center.”

This story is close to my heart because it revolves around The New Republic (TNR), a weekly magazine I fell in love with in the 1990s and that I dearly miss today. Among other things, I could always count on TNR for intelligent, surprising analysis rather than today’s predictable political bias.

This story is close to my heart because it revolves around The New Republic (TNR), a weekly magazine I fell in love with in the 1990s and that I dearly miss today. I could always count on TNR for intelligent, surprising analysis rather than today’s predictable political bias.

In this fragile and tribalized era, a magazine that puts intelligent analysis above political bias sounds downright quaint. This political bias, however, has had a troubling effect on our journalism, in at least three ways.

One, a loss of trust. If I feel that a writer or publication will bash only the “other side” but rarely if ever their own side, I don’t trust them. Their objective is not to pursue truth but to help one side win. The truth doesn’t care who wins; the truth itself is a victory.

The second effect is boredom. Ideological bias makes journalism dull and predictable. If I feel that a writer is wearing a uniform for a political party, I doze off. Nothing he or she writes will ever surprise me. These are writers at the mercy of a political agenda, which makes them the most boring kind of writers.

In its heyday, under the ownership of Martin Peretz, TNR was anything but boring. I would read a biography of John Adams that got rave reviews, for example, and then I’d open TNR to discover a brilliant, dissenting take on the book.

In addition to TNR’s well-known and well-earned popularity in the halls of power, its lesser-known quality was its delivery of sheer intellectual delight. Everything from politics to culture aimed to provoke thought. Its secret motto could well have been, “Thou shalt never bore.”

The third troubling effect of political bias has been an erosion of culture. “Politics seems everywhere to have swamped culture,” Joseph Epstein writes in this month’s Commentary. “It has not merely overwhelmed culture as a subject of interest but has infiltrated it through political identity and correctness… Culture seeks out the best, irrespective of race, color, or creed. Contemporary politics puts diversity, inclusiveness, equity above quality, and respects only the divisions of race, color, and creed.”

Epstein cites examples of general interest magazines like the old TNR which have become “more and more political in character.” The New Yorker, for example, “never descended to the level of party politics until the turn of the new century, when it began attacking George W. Bush and Dick Cheney, laid off Barack Obama, and went into high dudgeon against Donald Trump. In doing so, the magazine has lost its cultural authority, the authority that comes with being above the ruck.”

Being above the ruck means being unafraid to embrace the complex truth wherever it takes you. As Bloch writes, “TNR was both influential and well-respected precisely because of its complexity — its willingness to call out both sides.”

The book highlights the influence of Jewish intellectuals to that golden age of vigorous journalism, offering a chance, Bloch writes, “to revisit a hugely important time in both Jewish and American history. Jewish intellectuals, previously shut out by both universities and established magazines, were finally given a well-respected platform to dissect and devise important ideas.”

It’s sad, surely, that so many of today’s Jewish intellectuals seem to have fallen under the mainstream spell of political and ideological bias. But let’s not be too surprised: this is yet another sign of how safely assimilated our Jewish intellectuals have become. They’re no longer the rebels trying to break through forbidden doors; now they’re the conformists keeping the rebels out.

This is yet another sign of how safely assimilated our Jewish intellectuals have become. They’re no longer the rebels trying to break through forbidden doors; now they’re the conformists keeping the rebels out.

Will Jewish intellectuals ever regain their dissenting mojo? There are more than a few courageous Jewish voices out there who are trying, among them TNR alumni. As Bloch writes, “[Peretz] ends the book with faith in the people he’s taught and worked with. And the truth is, most of us who worked there will never be silent about how far journalism has fallen, and the dangers of extremism and insipid ideology. We will continue to try to reteach the world the true meaning of liberalism.”

Amen to that. Our new republic needs it.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.