Korach is one of Biblical tradition’s greatest villains, and when comparing him to today’s national leadership one wonders if the writers of the Biblical tale didn’t have a crystal ball that projected them into this era.

This week’s Torah portion Korach (Numbers 16:1-18:32) tells the story of a major rebellion led by Korach and 250 Israelite leaders.

Korach was the first cousin of Moses and Aaron (Exodus 6:18-21), a member of the priestly class and part of the ruling elite. The leaders around him are described as “Princes of the congregation, the elect men of the assembly, men of renown.” (Numbers 16:2) The Talmud says of them “that they had a name recognized in the whole world.” (Sanhedrin 110a).

Despite his elevated status Korach wasn’t satisfied. He challenged Aaron’s exclusive right to the priesthood, and his cohorts Dathan and Abiram questioned Moses’ leadership. Korach’s goal was to unseat the divinely chosen leaders. He appealed to the people to overthrow them using religious language and espousing the importance of rotating leaders in office, all of whom were equally worthy.

“And they assembled themselves together against Moses and … Aaron, and said [to them], ‘You take too much upon yourself, seeing that all the congregation are holy, every one of them, and the Lord is among them.’”

Though they spoke the language of “democrats,” Korach and his minions weren’t democrats at all; they were demagogues who manipulated and incited the masses for their narrow self-interests.

Rabbi Moshe Weiler, the founder of liberal Judaism in South Africa, wrote that “Theirs [i.e. Korach and his cohorts] was the pursuit of kavod, honor and power, in the guise of sanctity and love of the masses.”

Onkolos (2nd century C.E.), in his Aramaic translation of the two opening words of the portion, Vayikach Korach (“And Korach took”) wrote It’peleg Korach (“And Korach separated himself”) suggesting that he didn’t consider himself to be one with the people nor was he interested in serving their interests. To use a modern analogue, he saw himself as above the law and wanted to have the power of a king.

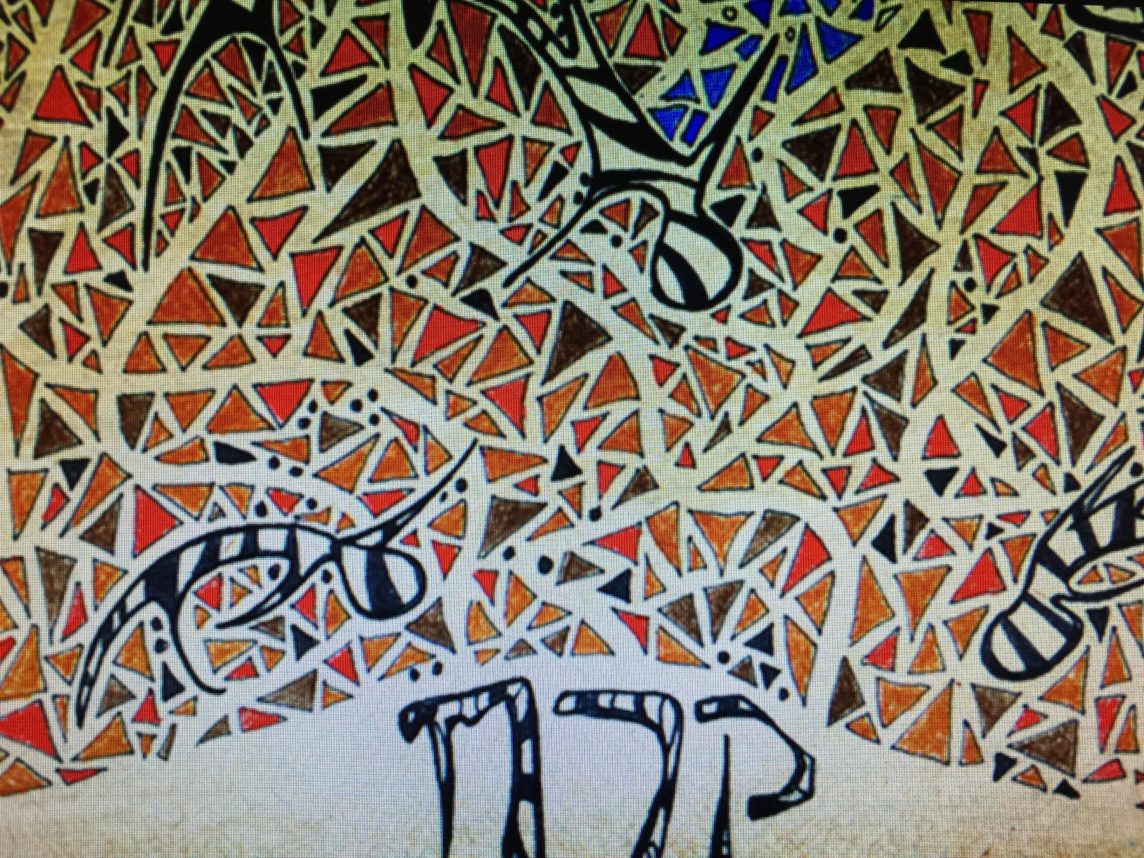

Korach sought power for power’s sake and he ignited a controversy based on ignoble motivations and nefarious goals leading to the devastation of the community. In the end, the earth swallowed the rebels alive and sent them to Sheol (the netherworld) in a spectacular inferno. (Numbers 16:31-35)

Korach’s eish ha-mach’loket (“fire of controversy”) became an eish o-che-lah (“a devouring fire”) that augured doom.

“The Sayings of the Sages” (Pirkei Avot 5:21) reflects upon Korach’s rebellion and distinguishes between two very different kinds of controversy. The first is healthy and useful and is pursued for the sake of heaven (l’shem shamayim). This kind of an argument brings about blessing and a stronger community. The second is the opposite. It represents a pernicious fight not based on lasting values. Rather, it brings disunity and destruction. In Judaism, Hillel and Shammai (1st century BCE) embodied the former, and Korach and his legions the latter.

Korach was a cynic. Moses was the opposite, the humble servant-leader.

Who are we? Do we resonate with the voice of Korach or the spirit of Moses?

Who are our leaders? Are they interested in power or the common good?

Turning inward for a moment, Rabbi Rachel Cowan opines that though all of us may aspire to be like Moses, Korach lives within each of our hearts too.

In thinking about ourselves and our leaders, the words of Maimonides remind us of the importance of pursuing higher virtue:

“The ideal public leader is one who holds seven attributes: wisdom, humility, reverence, loathing of money, love of truth, love of humanity, and a good name.” (Hilchot Sanhedrin 2:7)

In our elections, Judaism teaches that we ought to be voting for servant-leaders and not self-centered aspirers to power for power’s sake.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.