The massacre of 11 people at the Tree of Life Congregation synagogue in Pittsburgh has prompted comparisons to the 1938 attacks on the synagogues of Germany, which occurred 80 years ago this week and became known as Kristallnacht. While the two events cannot be equated, they impose profound burdens on our memory.

In the aftermath of Pittsburgh, we have seen an outpouring of reaction against hatred directed at Jews. Pittsburgh’s mayor and police chief were on the scene at the synagogue and condemned the violence. The media have covered the story with sympathy for the victims and disdain for the killer and the hatred for which he stands. The Pittsburgh Steelers football team showed support for the community by incorporating a Jewish star in its logo, and some of its players wore the star during their Nov. 4 game. The Muslim community put political differences aside and raised more than $200,000 in solidarity with the Jews. Innumerable other actions across this country voiced condemnation for anti-Semitism and concern and support for the Jewish people.

Indeed, the events since the Oct. 27 massacre have been moving, haunting, angering — and, at times, heartwarming. They provide us with a perspective to the events of 80 years ago that enables us to reflect upon how our world has changed, but also to clarify the persistent challenges that continue to confront us.

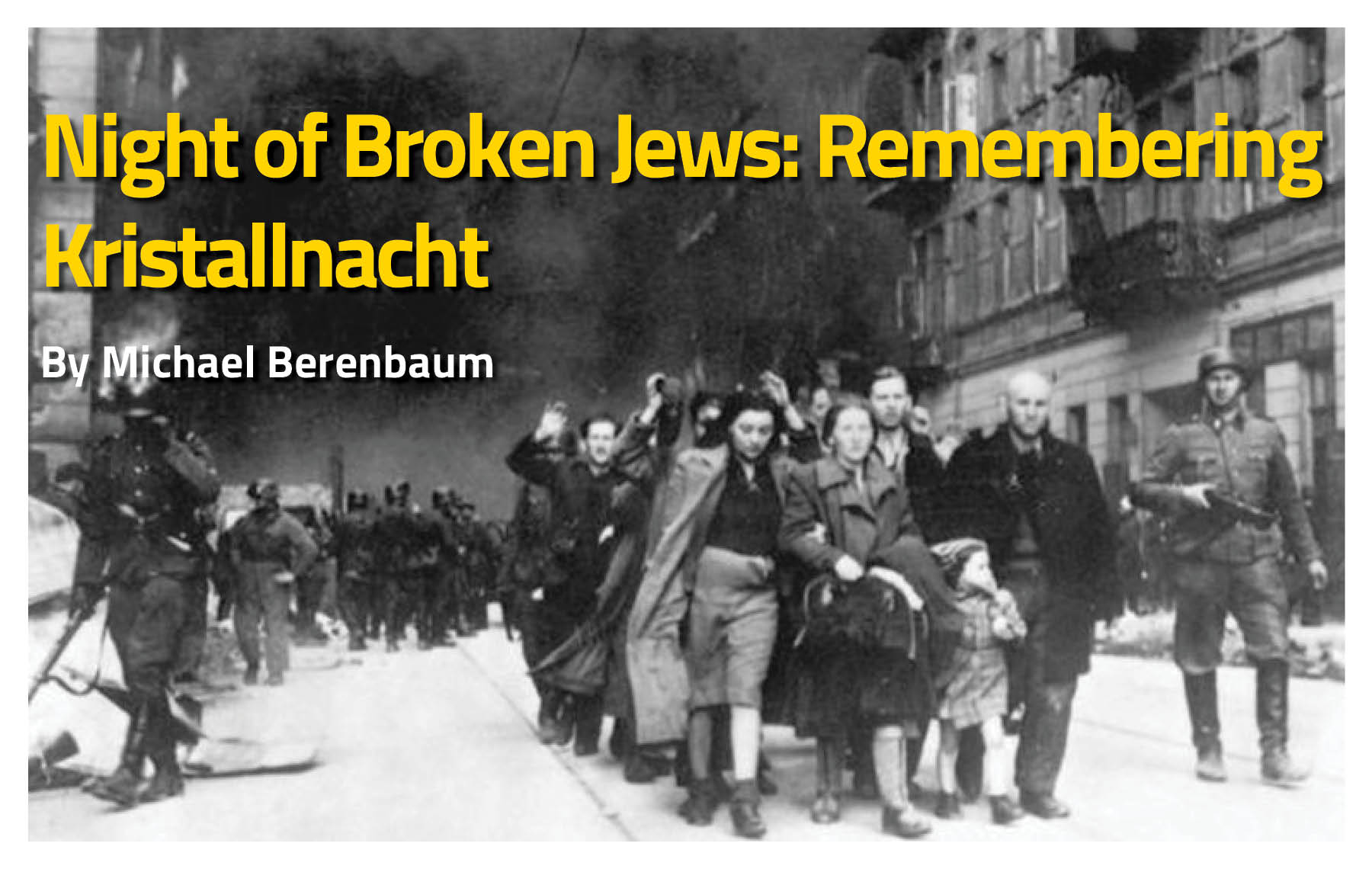

On Nov. 9-10, 1938, a series of pogroms took place throughout Germany. More than 1,000 synagogues were burned, their pews destroyed, their sacred Torah scrolls and holy books set aflame. More than 7,000 Jewish businesses were ransacked and 30,000 men from ages 16 to 60 were arrested and sent off to newly expanded German concentration camps, most especially Dachau, Sachsenhausen and Buchenwald. These pogroms were given a fancy name by which they are best known: Kristallnacht.

Over the past 35 years, Germany has ceased to use the term Kristallnacht, but rather refers to the event as the Reich Pogroms of November 1938. Crystal is beautiful. Crystal has a certain delicacy to it. Reich Pogroms tells a much deeper truth: state-sanctioned violence against the Jews.

There were 2,200 synagogues in Germany for 525,000 Jews — an average of nearly 240 members per congregation. Those synagogues became part of the public presence of Jews in German society, often built in triangulation with Roman Catholic cathedrals and Protestant churches to indicate that Germany was a pluralistic, multireligious society. Synagogues were an expression of the great progress that the Jews had made within Germany. By constructing buildings of significance, Jews made their presence and their prominence manifest.

So what the Nazis essentially did that night — in the most physical, most public way imaginable — was to show how far they were willing to go, what price they were willing to pay to tear the Jewish community out of the fabric of Germany. (Quite the opposite of the reaction we have seen in the United States after what happened in Pittsburgh.)

The Anti-Semitic Prelude

Hitler came to power with an anti-Semitic, racist and expansionist agenda. He told the world what he was going to do in his book, “Mein Kampf,” and in many public addresses. But there was a disconnect between what his audiences heard him say and what they believed he might do. He simply was not believed. Conservative political leaders presumed that once he was in power, the responsibility of office would force him to moderate. They would be there to guide him, to control him.

Yet, Hitler was allowed to do what he said he was going to do, and German policy evolved from 1933 onward to pursue his two main goals: the racial policy — to establish the supremacy of the master race; and the expansionist policy — to give Germany “Lebensraum,” or living space to be able to breathe, prosper and expand.

The anti-Jewish policies happened in waves.

Hitler came to power on Jan. 30, 1933. The Nazi Party’s first attack was on Germany’s political institutions — the burning of the Reichstag and then the enabling legislation that suspended parliamentary rule and gave Hitler dictatorial powers. On March 22, 1933, the first concentration camp was established in Dachau; and on the following April 1, the first attack was committed against Jews — the boycott of Jewish businesses. The boycott was followed seven days later by the expulsion of Jews from the civil service, which included teachers in high schools, professors in the universities, doctors and nurses who worked in hospitals, lawyers and judges as well as ordinary civil servants.

And on May 10, on Hitler’s 100th day in office, books deemed un-Germanic were burned — primarily, but not only, those of Jewish authors. Books by Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein, but also by Jack London and Helen Keller went up in flames. (A century earlier, the great German writer of Jewish origin, Heinrich Heine, had said, “People who burn books ultimately burn people.” The time between book burning and people burning would be eight short years.)

“I would not like to be a Jew in Germany.” — Field Marshal Hermann Göring

After the book burnings, anti-Jewish policy stabilized for a time and a “new normal” came into being. Jews lived in enormous insecurity, not knowing if things would get worse, get better or be stabilized.

If you believed the situation was terrible and only going to get worse, you took necessary steps to leave. If you believed the situation could not get much worse, would be stabilized and you could endure it, then you stayed. If you stayed too long, you were murdered.

Until the outbreak of war, German policy was designed to force the Jews to emigrate. If German national policy and the behavior of ordinary non-Jewish citizens would make life difficult for the Jews, they would leave. About 30,000 Jews (roughly 5 percent of the country’s Jewish population) left in the first months that Hitler came to power. Sadly, some returned after a time and some did not go far enough. They came under German domination again in 1940 when the Western European countries to which they had fled were invaded by the Wehrmacht.

In 1935, the Nazis defined Jews biologically, based on their grandparents’ religion. Their policy created a bizarre situation in which many Roman Catholic priests and nuns, and Protestant ministers and theologians who had Jewish grandparents but had been baptized as Christians were defined by the state as Jews. The policy also created a peculiar anomaly in which the Christian churches fought the state primarily over those people of Jewish origin whom they regarded as Christian, but the churches did not raise the larger issue about the general policies of discrimination and anti-Semitism.

In 1936, anti-Jewish policy stopped for a time when the Summer Olympics came to Berlin. Graffiti was removed, segregated benches were covered and the Nazis were instructed to be on good behavior.

The Role of the Synagogue

Let’s talk for a moment about the synagogue. But before we do, I want to establish a principle often overlooked in Holocaust history: Just because Jews were powerless, it did not mean they were passive. The problem was not that Jews didn’t want to leave. The problem was that there was nowhere to go that could absorb so large a population.

The way that synagogue use evolved tells us a lot about the strength of Jewish activism.

On Monday night, the synagogue became a theater because Jewish actors could not perform on the German stage. On Tuesday night, it became a symphony hall as Jewish musicians were dismissed from German orchestras. On Wednesday night, it became an opera house, because opera singers needed a place to earn a living.

“Most Jews were without illusions. Jewish life in the Reich was no longer possible. Some committed suicide. Most tried to leave. They had nowhere to go.”

On Monday morning, the synagogue became the place for distribution of welfare. Throughout the weekdays, the synagogue served as a school for Jewish children expelled from German schools. Their teachers were often professors, writers and artists struggling to survive in a new world. The art teacher might be a world-class artist; the music instructor, a concert pianist. The Jewish school was the safest place for a Jewish child, yet the most dangerous part of the students’ day was walking to and from school. Harassment was routine, bullying was accepted, violence was sanctioned.

Adult classes also were convened in the synagogue, teaching Jews “mobile professions” because the best way to survive and the best way to leave the country was to have those types of jobs. Plumbers, electricians, agricultural workers, bookkeepers, nurses, architects and musicians were mobile professions. Doctors, lawyers and accountants — whose licensing and/or knowledge of the law was fundamental to their work — found resettling cumbersome, as did writers whose expertise in the German language might limit their opportunities in a new land.

The synagogue also was a place where people who didn’t know what it really meant to be Jewish were taught about Judaism.

Jewish philosopher Martin Buber stayed until March 1938, almost to the very end, because he had founded an institute for adult Jewish studies. He tried to give people inner resources with which to face extreme degradation and humiliation, and the spiritual capacity to wear the Jewish star with pride.

The synagogue remained a place where prayers were recited, but prayers took on a new meaning.

Rabbi Leo Baeck wanted to teach the Jews how to respond to the life they were living. He composed a prayer for Yom Kippur 1935, which was read in synagogues throughout Germany on Kol Nidre. The prayer included, “We bow before Him, and we stand upright before men,” which was a way to tell the community on the most sacred of Jewish nights that part of being a Jew meant to stand against the idolatry and injustice surrounding them.

Rabbi Joachim Prinz, one of the last rabbis in Berlin, was prohibited from preaching in 1937. He asked a Gestapo officer: “Can I lead my congregation in prayer?” The Gestapo officer complied. So Prinz read aloud the line that traditional Jews read three times a day, and he had his congregation read it again and again in Hebrew — a language the Gestapo officer could not understand: “Ve chol a choshvim olay ra’ah, meheyra hofer atzotam ve kalkel maschshevotam” — “And all who plan evil against me, quickly annul their counsel and frustrate their intentions.” In other words, “Let God confuse our oppressors.”

The Event Itself

On the evening of Nov. 9, 1938, anti-Jewish violence erupted throughout the Reich, which now included Austria. The outburst appeared to be a spontaneous expression of national anger at the assassination of a minor German embassy official in Paris on Nov. 3 by a Polish-Jewish youth, Herschel Grynszpan, who was angered by the expulsion of his family from Germany and the Polish foreign ministry’s refusal to allow their return to their homeland by invalidating their passports.

The assassination became, in fact, the pretext for what was to follow, with the violence choreographed in detail. At 11:55 p.m. on Nov. 9, Gestapo Chief Heinrich Mueller sent a telegram to all police units: “In shortest order, actions against Jews and especially their synagogues will take place in all Germany. These are not to be interfered with. …” Police were to remain bystanders to the violence, but they were to arrest its victims. Fire companies were instructed not to protect the synagogues, but to ensure that the flames did not spread to adjacent Aryan properties.

Within 48 hours, more than 1,000 synagogues were burned, along with their Torah scrolls; 30,000 Jews were arrested and sent to concentration camps; 7,000 Jewish-owned businesses were smashed and looted; and 236 Jews were killed. Jewish cemeteries, hospitals, schools and homes were destroyed.

Hour after hour, the pace of the pogrom intensified. No Jewish institution or business or home was safe. The terror directed at the Jews was often not the action of strangers but neighbors. Most Jews were without illusions. Jewish life in the Reich was no longer possible. Some committed suicide. Most tried to leave. But they had nowhere to go!

The Aftermath

The Nazis, too, had learned important lessons. Many urbanized Germans held bourgeois sensibilities and opposed the events of Kristallnacht. Consequently, the sloppiness of the pogroms and the explosive violence of Nazi storm troopers soon were replaced by the cold, calculated, disciplined and controlled violence of the SS, the elite guard of the Nazi Party. The SS would dispose of the Jews out of the view of most Germans.

“What the Nazis essentially did that night was to show how far they were willing to go to tear the Jewish community out of the fabric of Germany.”

On Nov. 12, 1938, Field Marshal Hermann Göring convened a meeting of Nazi officials to deal with the problems that resulted from Kristallnacht. Historians are fortunate that the stenographic records of that meeting survived, for few documents reveal more candidly and more directly the German policy toward the Jews at this transitional moment. Several government ministries had much at stake in the outcome of the meeting. They had urgent justice and economic matters to deal with, including how the insurance industry, which stood to lose huge sums of money if it were to pay claims from those whose property had been destroyed.

Göring was clearly disturbed by the damage from the two-day rampage — not to Jewish shops, homes or synagogues but to the German economy. He said it would be insane to burn a Jewish warehouse and then have a German insurance company pay for the loss. Why should Germany suffer, not the Jews? The idea was introduced to solve the Jewish problem once and for all, but in 1938 its meaning was in economic terms. (Only later, by 1941, would the language be genocidal.) By a series of policy decisions, the Nazis transformed Kristallnacht into a program eliminating Jews from German economic life.

Several concrete actions were taken: The community was fined 1 billion Reichmarks ($400 million), Jews were declared responsible for cleaning up their losses and were barred from collecting insurance. Göring ordered that the booty in furs and jewels stolen from Jews by looters belonged to the state, not to individuals.

In the end, Göring expressed regret over the whole messy business. “I wish you had killed 200 Jews and not destroyed such value,” he said, concluding on a note of irony: “I would not like to be a Jew in Germany!”

On Nov. 15, 1938, Jews were barred from schools. Two weeks later, authorities were given the right to impose a curfew. By December, Jews were denied access to most public places. By January, all Jewish men had to adopt the middle name of Israel; all Jewish women, Sarah.

The November pogroms were the last occasion of street violence against Jews in Germany. While Jews could leave their homes without fear of attack, a lethal process of destruction that was more effective and more virulent was set in place.

The Jews who were arrested and sent to concentration camps were the “lucky ones.” At that time, if they could get a visa to leave the country, they could be released from the concentration camp. And Jewish women — mothers for their sons, wives for their husbands, sisters for their brothers, friends for friends — left no stone unturned to get their men released. It was no longer a question of whether to leave or when to leave, but only how to leave — and no price was too steep to pay.

The American response to the 1938 pogroms was mostly rhetorical and symbolic. By 1938, the United States understood and internalized the value of freedom of religion. No other event garnered such universal condemnation. From the extreme right to the extreme left, Catholics and Protestants of every denomination condemned the violence. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called the U.S. ambassador to Germany home — the most powerful response among world leaders — but he didn’t sever diplomatic relations.

At the same time, American public opinion showed little support for changing immigration policies to take in Jewish refugees. It was as if the American people said: We despise what Germany is doing, but that doesn’t mean our immigration policy has to change. We don’t want the Jews here. They can’t take American jobs.

“Just because Jews were powerless, it did not mean they were passive.”

In Germany, some Jews were so certain that events were only going to get worse that they sent their children to England, into the arms of strangers on what became known as the Kindertransport. Ten thousand Jewish children were sent to England, many of whom never saw their parents again.

An effort to bring 20,000 children to the United States, led by Sen. Robert Wagner of New York and Congresswoman Edith Rogers of Massachusetts, failed. Congress feared the children would grow up and take American jobs.

By attacking the synagogue, the Nazis attacked not only the heart and soul of the Jewish community but the institution that had responded to the catastrophe. The Nazis deprived Jews of anything roughly resembling a public life or a communal life. And they violently ripped Jews out of German society.

This was the end of the beginning and the beginning of the end.

Today, the response to the Pittsburgh killings exemplifies another way to respond to such violence. Hatred can be defeated if people of good will and elemental decency join together to show that they will not tolerate it, exacerbate it or encourage it.

Michael Berenbaum is director of the Sigi Ziering Institute and a professor of Jewish Studies at American Jewish University.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.