Israeli reserve combat soldiers of the Alexandroni brigade during a training exercise on Jan. 4, 2024 in Golan Heights. Amir Levy/Getty Images

Israeli reserve combat soldiers of the Alexandroni brigade during a training exercise on Jan. 4, 2024 in Golan Heights. Amir Levy/Getty Images I have no way of answering the following two questions:

Are Israeli reservists naive or smart?

Are Israeli reservists made of special cloth?

These are two intriguing questions, given the findings of a survey that examined the views of those who have a connection to the reserves — we’ll call them “the reservist community” — versus those who have no connection to the reserves.

Reserve duty is something many Israelis are familiar with, and most Americans can’t fathom. A lawyer, a car mechanic, a farmer, a student, a teacher, a tech executive — all civilians — leave home, put on a uniform, and go back to being soldiers. In the war that Israel is now fighting, about half a million Israelis served as reservists. Many of them left their families behind – wives, children, a job, a daily routine. They are a unique bunch, especially those who serve in combat units on the frontlines.

Uri Keidar from the organization Israel Hofsheet came up with the idea to identify these people in a survey. So we asked: Have you or a close family member (nuclear family) served in the reserves in the last few months? It was possible to answer: “Yes, me,” or “Yes, a family member” or “Yes, both,” or “No.” Those who marked one of the first three categories are the “reserve community.” And when we examined their attitudes separately from the views of those who have no such connection to reserve duty, we found something interesting: there is, indeed, a clear difference. Reserve duty makes a difference. Meaning: Either those who serve, from all sectors, are a special breed to begin with. Or it’s the act of going to serve that changes people.

“The result was inspiring: in the reserve companies, hatred was erased and replaced by brotherhood, heroism and solidarity. The melting pot of the new Israeliness was created in the reserve brigades.” – Micah Goodman

Israeli philosopher Micah Goodman proposed such a possibility in an article he published about a month ago, and it is echoed in his forthcoming book. Goodman wrote: “After nine months of national strife, war broke out. Over 300,000 Israelis enlisted in the reserves. They gathered into units and brigades where Israelis with different opinions and different identities rubbed against each other in the most intense way imaginable, and all this face to face, without digital mediation, and over a long period of time. Reluctantly, they went through a detoxification workshop. The result was inspiring: In the reserve companies, hatred was erased and replaced by brotherhood, heroism and solidarity. The melting pot of the new Israeliness was created in the reserve brigades.”

Is Goodman right? He assumes that when people put on uniform and serve with their comrades, they change. And while I can’t confirm such exact assumption, I can confirm the conclusion that the “reserve community” is indeed less polarized and more socially conciliatory. Whether that’s good or bad is a debate for another day (some people might want Israelis to keep their ideological zeal), but for those wanting conciliation, the reserve community portends hope. It is a community of Israelis who are less willing to quarrel over all kinds of social issues. For example: The percentage of Israelis who prefer not to address the controversial issue of “civil marriage” in Israel anytime soon, because it is a divisive issue, or because “there are more important things,” is higher among members of the reserve community. In other words, these Israelis prefer to postpone what could become another reason for social quarrel. Thirty-one percent of the seculars who wore a uniform in the last couple of months said no to having this debate about civil marriage now, compared to just 20% of the seculars who did not wear a uniform (or have a family member who did).

And they — members of the reserve community — are also more optimistic. Which brings us back to the first question we don’t have an answer to: Is it because they are more naive or because they are smarter? We don’t know. It’s too early to tell. But when we ask Israelis “about the relations between religious and seculars,” and whether these relations will “improve after the war” or “will not improve after the war,” we see again the clear differences between the reservists and the non-reserves.

Forty-seven percent of the religious reservists (and their family members) think that the relations will improve, compared to 41% of those who are not part of the reservist community. Among seculars, the difference is even greater: 39% think that the relations will improve, compared to 15% of those who did not serve. Are they naive or wise? Did they become more optimistic as they sat together – religious and secular reservists – in tents, bunkers and tanks? If that’s the case, then we might have found a solution to social polarization in Israel and elsewhere: send them all for a month or two in uniform. They will both protect us from our enemies, and along the way they also will learn to stop being enemies.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

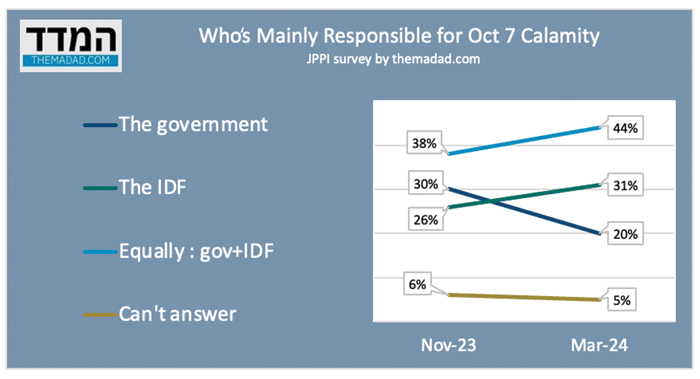

In the months since the beginning of the war, Israelis were exposed to information about the mishandling of information and lack of preparedness in the IDF prior to the Oct. 7 attack. This brought about a change in attitudes. Here’s what I wrote, followed by a graph:

The less surprising thing that happened is that even more coalition voters shifted the main responsibility for the calamity from the government to the IDF and Shin Bet … The more surprising thing — and perhaps not surprising, because in the end when reality hits you, it’s hard to ignore it — is the change in attitudes of the opposition voters. No longer believing that the government is mainly responsible for the “mechdal” (failure) a majority of them now divide the responsibility equally between the government and the security agencies.

A week’s numbers

More opposition voters realized: It’s not just the government’s fault.

A reader’s response:

Mia Lowenthal asks: “Shmuel, do you think Trump is going to be better for Israel?” My answer: I have no clue what policy Trump would pursue in the Middle East, and to be honest, I’m not sure that he has one.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.