Ryohei Noda/Flickr Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

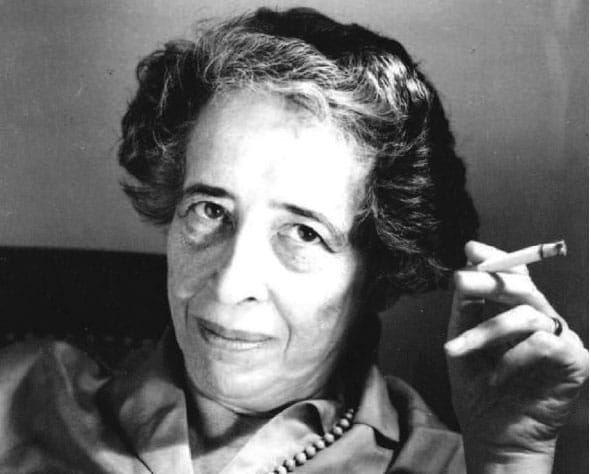

Ryohei Noda/Flickr Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) “Arendt” was a name I heard quite often growing up, but one I didn’t think much of. I knew that Hannah Arendt had written “The Origins of Totalitarianism” and “Eichmann in Jerusalem,” two seminal pieces of 20th-century literature that were never assigned to me even in the most comprehensive courses on despotic ideologies. Syllabus after syllabus was barren of her work, which made no difference to me—I figured there must have been a good reason for it.

As I began my career in the Jewish world, I learned that the American Jewish perception of Arendt, certainly in my community of Jews who left Europe before the Shoah, was of a commanding intellectual with the insight to illuminate the human nature behind the Holocaust. This differs dramatically from the common European Jewish and especially Israeli perception of her, as a narcissistic observer who blamed the Jewish people for their own destruction while casually chain-smoking from her apartment in New York, miles from harm’s way. In reading her books for the first time and delving into the world of knowledge she had constructed for herself, I realize that neither of these characterizations of Hannah Arendt are entirely accurate.

To American Jews, this remains an intriguing insight that does nothing to absolve Nazis, but rather explains the psychology behind mass atrocity.

“Eichmann in Jerusalem” was never presented to me as controversial. It is in this 1963 collection of essays, originally published in The New Yorker as a commentary on trial of Nazi Adolf Eichmann, that the phrase “banality of evil” first appears, referring to Arendt’s hypothesis that the greatest evil in the world is committed not by savages and monsters but by ordinary men: nobodies, bureaucrats, meek subordinates who swallowed their orders and executed them without second thought. Arendt illustrated a portrait of Eichmann not as a brazen antisemite, but as a sluggish old man with a head cold who was swept away in the hateful climate of his age. Duty and loyalty were everything to him, the consequences of which never seemed to faze him. To American Jews, this remains an intriguing insight that does nothing to absolve Nazis, but rather explains the psychology behind mass atrocity. But for Europe’s Jews and Israel’s, fifteen years from the gas chambers, who wanted nothing more than to see Eichmann as the vicious tyrant he was and to have him hanged as such, Arendt appeared to be if not defending than at least minimizing the responsibility of all those in Nazi high command who “followed orders.”

When Arendt discusses the Judenrat, Nazi-designed Jewish councils created to manage the Jewish communities and in some cases cooperate with the Nazis in the liquidation of ghettos and transport of civilians to concentration camps, she just adds insult to injury. She writes:

“Wherever Jews lived, there were recognized Jewish leaders, and this leadership, almost without exception, cooperated in one way or another, for one reason or another, with the Nazis. The whole truth was that if the Jewish people had been really unorganized and leaderless, there would have been chaos and plenty of misery but the total number of victims would hardly have been between four and half and six million people.”

Arendt continues, “To a Jew, this role of the Jewish leaders in the destruction of their own people is undoubtedly the darkest chapter of the whole dark story.”

Given the provocative nature of this passage, the outrage from her fellow Jews is understandable. In fact, The New Yorker received hundreds of rancorous complaints. It is rumored that the State of Israel itself attempted to prevent Arendt from publishing, and even personal friends of Arendt distanced themselves from her on account of the perception that she had betrayed her own people. This pain is real. Indeed, had I been alive then, I might have very well shared the same revulsion—bewildered by Arendt’s insensitivity regarding the choices the Jewish people were forced to make under the most depraved of circumstances, each individual a victim in his own way. The pages in her book dedicated to the Judenrat remain, at the very least, offensive, and a mischaracterization of the number of victims who died and how.

She was bound by her interpretation of truth, not by national or religious sentiments.

But Arendt did not report on the trial of Eichmann to defend the Jewish people or even to indict the evils of Nazism. Between her ears was the brain of a journalist and a philosopher, not of an ardent Zionist (though she worked with Zionist organizations in her youth) or a human rights prosecutor. She was bound by her interpretation of truth, not by national or religious sentiments. Furthermore, it is not entirely fair to brand her an enemy of the community, considering Israel was also harsh when it came to those believed to have collaborated with Nazis. Israel passed “The Law of Punishment of Nazis and Their Collaborators” in 1950, prosecuted collaborators throughout the decade, and even tried Rudolf Kastner, a politician in the Labor Party, for alleged crimes of cooperation during the war. Arendt was harsh, but perhaps her ideas came from a place of anger, not unlike the anger of her Jewish and Israeli contemporaries.

Perhaps we might see Arendt not as a reckless provocateur or self-hating Jew, but as a thinker who sought to understand the reality of the world. Possibly the most prescient takeaway from Arendt’s work, spanning from the infamous Eichmann trial to her broad writings on human nature and authoritarianism, was, in her own words, the “totality of moral collapse” in Europe under the Nazis. She was able to investigate how and why and under what conditions genocide can take place, and in an era in which the violation of rights is pervasive I find her work not comforting, but perhaps necessary. Her work should certainly be listed in class syllabi, considering the discussions and controversies she provokes are still of paramount importance.

Blake Flayton is New Media Director and columnist at the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.