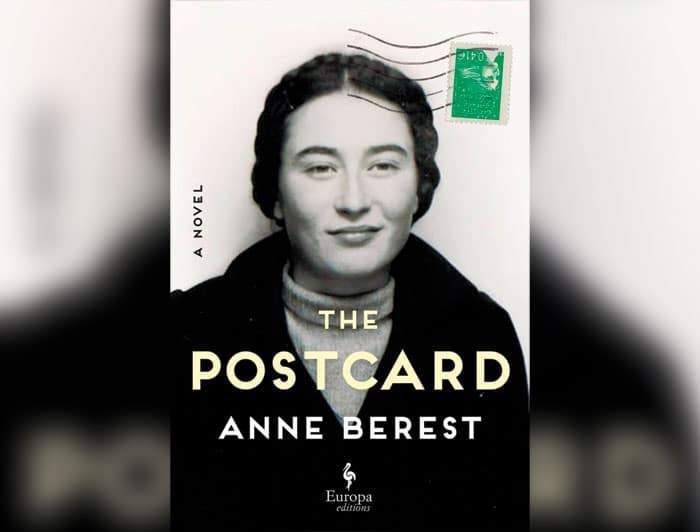

Anne Berest’s great-grandparents, along with her grandmother’s sister and brother, were taken from their home in France in 1942 and murdered in Auschwitz. Their names were Ephraïm, Emma, Noémie and Jacques. One day, in the 21st century, these names show up on a postcard at the home of Anne’s mother, addressed to Anne’s dead grandmother. The postcard has no signature; the sender is unknown. These are historical facts and also the basis of Berest’s novel, or work of autofiction, “The Postcard.”

Is Anne being taunted? Is this a moment like the ones the thinly fictionalized narrator experienced as a child, when, for instance, a swastika was painted on her house one night? Or when she lost her coveted place as the teacher’s pet after her class was assigned the making of a family tree and Anne included the word “Auschwitz” on hers far too many times? Or when the school chose her and a boy, the two Jewish pupils, to be decapitated in a play about the French Revolution? In other words, is the postcard a modern act of antisemitism?

We read of love, lost and found; of big dreams; of great achievements. But, throughout, we know how it all ends: in Auschwitz.

In the novel, Berest uses the arrival of the postcard to tell the story of her ancestors. The first half of the book beautifully and grippingly follows the lives of Ephraïm and Emma Rabinovitch and their children Myriam (Anne’s grandmother, the only survivor), Noémie and Jacques. It is, in Anne’s mother’s words, “a blended story,” made of known fact, theories and stories. The narrative takes us from Moscow to Riga, through Lithuania, Poland, Hungary and Romania, across the Black Sea and the Mediterranean to Haifa and then Migdal before the Rabinovitches settle in France. We read of love, lost and found; of big dreams; of great achievements. But, throughout, we know how it all ends: In Auschwitz.

The second half of the novel returns us to the contemporary era and to the search for information. Berest uses the novel not only to tell the story of her family but also to try to understand what it means to be Jewish. Anne remembers Jewish girls in her 10th-grade class saying they couldn’t participate in a tournament because it was Yom Kippur, which makes her realize that she might be “Jewish,” but she doesn’t belong to a community. Not a Jewish community, anyway. “I feel like the only thing I truly belong to is my mother’s pain,” she says. “That’s my community.”

Despite generations of secularism — there is a thematic questioning of the protection assimilation offers — even Anne’s daughter needs to negotiate her Jewishness. “I don’t think they like Jews very much at school,” she tells her mother. Anne is unsure how to react. “I didn’t want to make a big deal out of it,” she says at a Seder to which she’s been invited — her first. “If you were truly Jewish, you wouldn’t take it so lightly,” she’s told.

At the end, however, Anne is convinced that while she might not understand what it means to be “truly Jewish” (or, for that matter, “not truly Jewish”), she does understand what it means to inherit the intergenerational trauma so prevalent in the children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors.

Berest has a colorful family history, full of talented and storied members. Her great-grandfather was the French avant-garde painter Francis Picabia. Her great-grandmother, Gabrièle Buffet-Picabia was the lover of Marcel Duchamp, as well as an influential art critic, writer and organizer in the French Resistance.

“The Postcard” isn’t about these famous family members, and as such, feels like a departure for Berest, who previously wrote a book about her great-grandmother with her sister Claire (in addition to “Gabriële,” Berest wrote about another well-known figure, the French writer Françoise Sagan, in “Sagan, Paris 1954”). “The Postcard” is about ordinary people, Jews, who were forced to move from place to place, but never managed to outrun the antisemitism that ultimately led to their demise.

As for the mystery that opens the novel, it is not a great mystery. The answer is there, throughout, if you’re looking for it. But this book is not a mystery novel, and the revelation doesn’t need to be a surprise; the poignant explanation is enough.

Karen E. H. Skinazi, Ph.D, is Associate Professor of Literature and Culture and the director of Liberal Arts at the University of Bristol (UK) and the author of Women of Valor: Orthodox Jewish Troll Fighters, Crime Writers, and Rock Stars in Contemporary Literature and Culture.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.