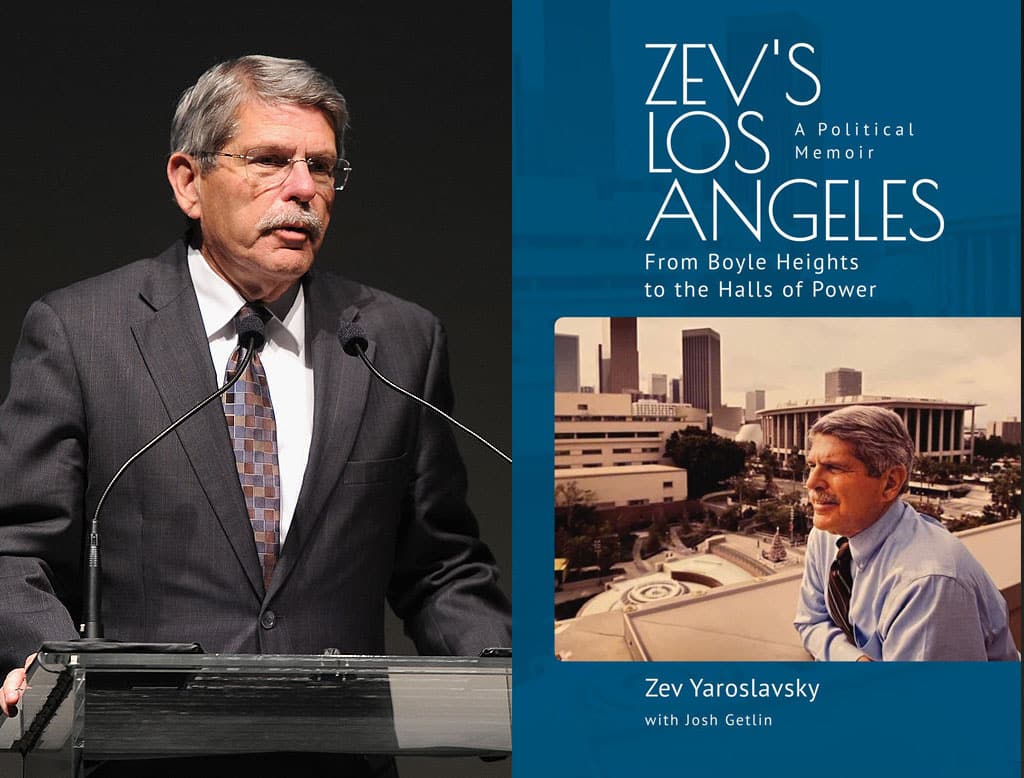

Zev Yaroslavky (Photo by Alberto E. Rodriguez/Getty Images)

Zev Yaroslavky (Photo by Alberto E. Rodriguez/Getty Images) “It’s easy to be cynical, but I’ve lived my entire life convinced that holding public office is one of the most important callings in a democracy—a singular opportunity to improve the lives of those we are elected to represent,” Zev Yaroslavsky writes in his new book, “Zev’s Los Angeles: From Boyle Heights to the Halls of Power. A Political Memoir.”

Yaroslavsky—former City Councilman, now retired from the County Board of Supervisors—has written, with Josh Getlin, an account of his years in government that will impress the most jaded critic.

How did Los Angeles change from having a notoriously skeletal public transit system to boasting a vast system of buses, subway, light rail and shuttles? How was Martin Luther King Jr. Hospital resuscitated, after being forced to close due to its dismal performance in one of LA’s most underserved communities? How did the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area come into being? In Yaroslavsky’s case: By plowing ahead through a migraine-inducing series of administrative roadblocks, justly or unjustly harsh public criticism, not-so-gentle pressure from powerful sponsors and “friends,” internal rancor and plenty of other difficulties.

And how did those at the heart of LA’s government respond among themselves to dramas like the hosting of the 1984 Olympics, the Ramparts police scandal and the 1992 Rodney King upheaval? Any political junkie, and particularly anyone with an interest in Los Angeles, will be curious to get Yaroslavsky’s take.

Yaroslavsky writes that he intended his book to be “a history as much as a memoir,” and the result is a studied account, written with an evident eye on posterity. Many of the pages describe his youth and family background, however, and these are some of the most affecting. He opens with a beautiful dedication to his late wife Barbara Edelston Yaroslavsky, the love of his life, without whom, he writes, none of his achievements would have been possible. He also gives tribute to forebears like his maternal grandfather Shimon Soloveichik, a fervent Zionist, whom he never met but tales of whom inspired Yaroslavsky. It’s easy to imagine his grandfather’s partisanship on behalf of the Jewish people playing a role in the young LA-born Yaroslavsky’s first political activism, on behalf of Soviet Jewry.

Many of the pages describe his youth and family background, and these are some of the most affecting.

There’s real story interest in these pages preceding Yaroslavsky’s ascent to public office. He traces his awareness about the plight of Soviet Jews to his bar mitzvah, when his aunts in Ukraine sent him a telegram congratulating him on his “birthday” and he was told it would have been perilous for them to refer to a Jewish rite. On his first visit to the Soviet Union, in 1968, relatives impressed upon him that “the walls have ears” and Yaroslavsky learned the power of fear and paranoia in a dictatorship. Upon returning home, he defied a representative of the Jewish Federation of Greater Los Angeles to organize a protest—the first of its kind in LA—against a visiting Soviet sports team on behalf of Soviet Jewry.

He went on to found California Students for Soviet Jews, which coordinated actions between his alma mater, UCLA, and other campuses; began a close working relationship with Si Frumkin of the Southern California Council on Soviet Jewry; and took part in the founding of the national Union of Councils for Soviet Jews. Through risky meetings with refuseniks in Moscow and Leningrad, relayed with a LeCarre-ish flavor, Yaroslavsky and his fellow activists documented the plight of Soviet Jewry. This helped enable the 1974 passage of the Jackson-Vanik congressional amendment, which imposed trade penalties on countries (read: the Soviet bloc nations) that restricted Jewish emigration and violated other human rights.

A sudden vacancy on the Los Angeles City Council in 1974 changed everything.

No one, Yaroslavsky relates, expected him to win the election. He was young and virtually unknown, running against some of the city’s most well-liked and -funded politicians. His victory surprised if not shocked everybody. Yaroslavsky’s account of his early days contains some funny (or not, depending on one’s perspective) gems—like the copy of the budget Mayor Tom Bradley arranged to be delivered to the new councilman, “like an arriving dignitary,” on the plush black seat of a Cadillac limousine. He early on learned to use the media to act as an intermediary between him and the public, leading to the joke, “Don’t ever get between Zev and a TV camera. You’ll get crushed.”

He also learned the variegated expectations of what it meant to be indispensable to his constituents in the Pico-Robertson area: from arranging to have pedestrian lights turn on automatically on Saturdays, so observant Jews could cross without jaywalking or pressing the (forbidden electric) button, to giving the sole eulogy for a man he had no memory of ever meeting.

A flood of weightier topics soon arrived to be tackled: desegregation of public schools, LA traffic woes, taxpayer and renter revolts, homelessness, police brutality and surveillance, city growth and development battles, coastal oil drilling. Yaroslavsky provides enough detail about each challenge to give a sense of the difficulties without being overwhelming. His descriptions of LAPD abuses of power, and his confrontations with LAPD brass, are extensive and sobering, however. Kerfuffles with Police Chief Daryl Gates yield some startling details, such as the chief’s reluctance to impose a curfew the night the Rodney King upheaval erupted: “If I do that, all of the restaurateurs in the city will go crazy,” Gates said as fires and violence raged. Yaroslavsky replied: “Daryl, no one is going out to dinner in LA tonight,” musing that things had reached a perilous state when someone like him was making tactical security recommendations to the LAPD’s police chief.

Yaroslavsky gives credit where he deems fit to individuals on the opposite side of the political aisle, such as Mayor Richard Riordan for his deft handling of the Northridge earthquake. Riordan could be brusque and autocratic, he writes, but his impatience with red tape proved valuable in this case: after sections of the city infrastructure collapsed, the mayor didn’t waste time laying out and proceeding on a plan to rebuild them.

The move to LA County Board of Supervisors initially proved unexpectedly difficult: Yaroslavsky remembers that the first thing he noticed was the “yawning silence that extended through the day.” He seldom heard from constituents; when he walked down the corridor in the Hall of Administration where his office was located, he heard “the lonely echo of my footsteps.” People’s eyes glazed over when he tried to describe the administrative maze overseen by LA’s Board of Supervisors; they only began to grasp the job when he told them the Supervisors oversaw a $32 billion budget and over 100,000 employees. It was in his capacity as Supervisor that Yaroslavsky helped bring to fruition some of his biggest projects: Disney Hall, the MTA’s Orange Line and the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area.

An obvious source of both pride and bitterness is his attempt in the first decade of the twenty-first century to tackle homelessness. Yaroslavsky created a pilot program, Project 50, that operated on the principle that homeless people should be provided with housing first, then offered programs to address any underlying mental or physical health issues, drug or alcohol addiction. Yaroslavsky’s team enrolled 75 homeless people in the initial pilot, hoping that its success would provide a model to expand its approach to the county’s 25,000 chronically homeless people. This latter hope was dashed. Although Project 50 was, Yaroslavsky reports, a success, he was unable to overcome the obstacles to expand it countywide. He also notes that he has “a profound sense of failure” over the longstanding poor performance and 2007 closure of Martin Luther King Hospital, although he successfully navigated the hospital’s resurrection in partnership with UCLA. For too long, he notes, LA’s most vulnerable residents were neglected by a bureaucratic, impersonal fiefdom, Los Angeles County—an apparatus “designed not to govern.”

Yaroslavsky has provided an engrossing account of a tumultuous era and the often-subterranean battles that have shaped the city of Los Angeles. He may even give the reader a new appreciation for the work of a politician.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.