With three bestselling World War II espionage thrillers to his credit, including “Into the Lion’s Mouth” and “The Princess Spy,” author Larry Loftis faced a dilemma. He’d already covered the four western Allied espionage outfits: MI5, MI6, SOE and OSS, and resistance activities in Portugal, France, and Spain. Where could he break new ground in his chosen genre?

He considered writing about Corrie ten Boom, whose family in Haarlem, Holland joined the Dutch resistance. They hid dozens of Jews and non-Jewish members of the Dutch underground, secreting them away in an ingeniously designed space behind Corrie’s bedroom closet. Corrie helped sneak 100 Jewish babies out of a nursery before the Nazis could carry out plans to kill every tiny orphan; helped plan raids to get food ration cards to distribute to Jews and performed many other feats of bravery.

But ten Boom was already fairly well known, particularly after the success of her 1971 memoir, “The Hiding Place,” which sold more than 4 million copies. Still, ten Boom’s deep Christian faith and belief in the power of love and forgiveness (shared passionately by her equally devout family members) made her story distinctive among those of other resistance members. Digging further, Loftis also discovered a treasure of archival material that pulled the curtain back on Dutch resistance efforts through the story of the ten Booms, revealing a much bigger, more astounding, and better documented story than what Corrie ten Boom had written in her slim memoir.

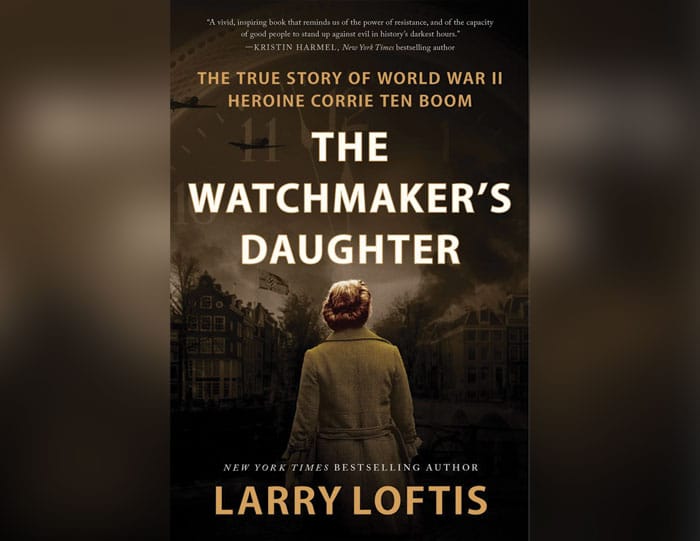

“The Hiding Place” is an unforgettable book, the story of quiet, determined, and faith-based heroism by an otherwise unassuming middle-aged Dutch woman. Larry Loftis’s new release, “The Watchmaker’s Daughter,” greatly expands her story and is the first major biography of Corrie ten Boom. While ten Boom didn’t keep a diary, several people very close to her did, including Hans Poley, the first permanent refugee to stay in the ten Boom home, as well as Peter van Woerden, one of Corrie’s nephews. Personal letters, photos, scrapbooks, and notes that belonged to Corrie ten Boom from the Billy Graham Center Archives at Wheaton College “offered the ‘perfect storm’ of scattered material and was precisely what I was looking for,” Loftis writes in his author’s note. “I knew I had the potential for a seminal book.”

Corrie, her sister Betsie, and their father, Casper, lived in a home known as the Beje (now the Corrie ten Boom Museum), where Casper, considered the finest watchmaker in all of Holland, ran his business on the ground floor. Corrie apprenticed with him and then studied watchmaking in Switzerland, becoming the first licensed female watchmaker in Holland. As members of the Dutch Reformed Church, which protested Nazi persecution of Jews as an injustice to humanity and an affront to God, the ten Booms were horrified by the German invasion.

When Corrie and her father first saw local Jews being rounded up and herded into trucks, Casper said, “I pity the poor Germans, Corrie. They have touched the apple of God’s eye.” A few years later, on February 28, 1944, the Gestapo raided the Beje, arresting Corrie, her sister Betsie, their 82-year-old father, and other family members living nearby. The six other residents of the Beje all made it into the hiding place and were not discovered. At the police station, a Gestapo officer offered to send Casper home if he promised “not to cause any other trouble.”

Corrie was 52 years old and already weakened by illness and the deprivations of war. Yet she miraculously survived ten months of brutality in two concentration camps, including the infamous cruelties of Ravensbruck, where her sister Betsie died.

“If I go home today, tomorrow I will open my door again to any man in need who knocks,” he said. Casper ten Boom died in prison nine days later. At the time of their arrest, Corrie was 52 years old and already weakened by illness and the deprivations of war. Yet she miraculously survived ten months of brutality in two concentration camps, including the infamous cruelties of Ravensbruck, where her sister Betsie died.

Loftis recreates the dramatic but purposeful atmosphere in the Beje, including practice drills for the residents all having to crawl into the hiding place in only 90 seconds; warnings of potential raids that forced some residents to flee to other safe houses; and the constant risk of detection: the Beje was only a few blocks from the local police station, and many Dutchmen were collaborating with the Germans. The ten Booms never sent anyone away, feeding them when food was already scarce, and acting against their character by lying to the police, claiming they had no knowledge of underground activities. Unfortunately, Corrie’s misplaced trust in one visitor claiming to be part of the resistance but who was actually a collaborator triggered the family’s betrayal.

Corrie and Betsie kept their faith through imprisonment, uplifting other prisoners with prayer and optimism. As Betsie’s health failed, she made Corrie promise to open healing centers after the war, where survivors could repair physically and emotionally. Corrie fulfilled her sister’s wish, helping to develop several convalescent centers in Holland and Germany. “Each had a hurt he had to forgive,” Corrie stated, “the neighbor who reported him, the brutal guard, the sadistic soldier. Strangely enough, it was not the Germans or the Japanese that people had most trouble forgiving; it was their fellow Dutchmen who had sided with the enemy.”

Corrie ten Boom consciously chose to forgive everyone involved in her own suffering, including Jan Vogel, the Dutchman who had betrayed her family. In a letter she sent to him six months after her release from Ravensbruck, she wrote, “The harm you planned was turned into good for me by God. I came nearer to Him. A severe punishment is awaiting you. I have prayed for you, that the Lord may accept you if you will repent … I have forgiven you everything. God will also forgive you everything, if you ask Him …”

She devoted the last 40 years of her life to a one-woman ministry of sorts, talking about her experiences and encouraging people to triumph over despair through faith and forgiveness. She traveled to sixty countries, from Uganda to Uzbekistan and dozens of other places, speaking to people of all walks of life: from prisoners in San Quentin to Pentagon officials. She was knighted by Juliana, Queen of the Netherlands and was honored as one of the Righteous Gentiles by the State of Israel. Her father and sister, Betsie, were also given that honor.

After her birth on April 15, 1892, Corrie’s mother, Cor, wrote in her diary, “What a poor little thing she was. Nearly dead, she looked bluish white, and I never saw anything so pitiful. Nobody thought she would live.” Obviously, this premature, sickly newborn had a tough inner core, living through hell on earth and for decades beyond. As Loftis wrote, “Corrie ten Boom’s legacy continues to sound out her message of faith, hope, love, and forgiveness.”

Judy Gruen’s most recent book is “The Skeptic and the Rabbi: Falling in Love With Faith.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.