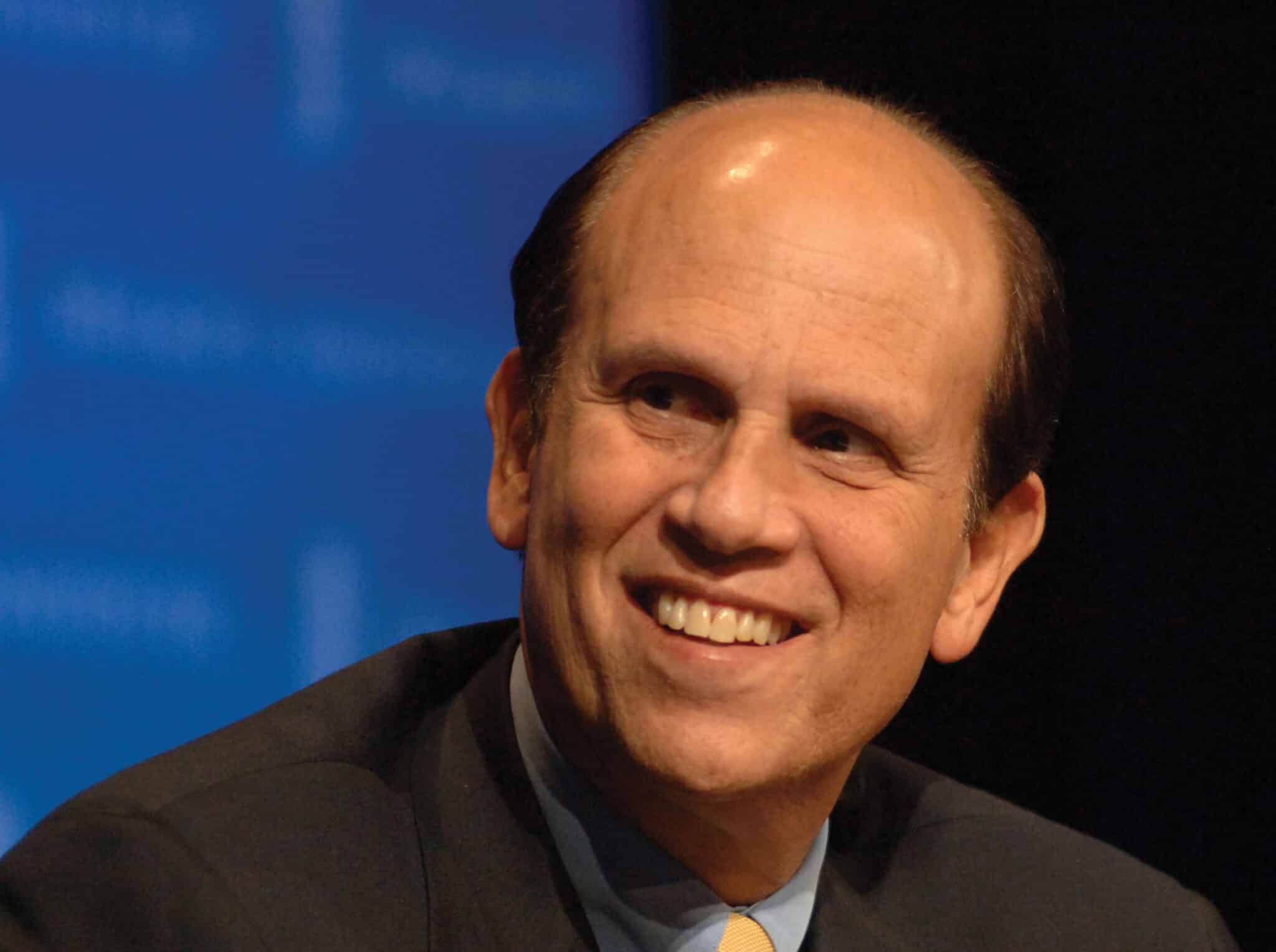

Photo by Larry Weisenberg/ CC BY-SA 3.0

Photo by Larry Weisenberg/ CC BY-SA 3.0 If you want to make my heart sing, just say the words “American Dream.” I am that corny immigrant from Morocco who believes in that idealized view of America, perhaps because I have lived it. I worked 12-hour days for many long years building with my partner an advertising agency that rose to be named “Agency of the Year” by USA Today.

On my long and often difficult journey to the rarefied air of the ad biz, at no point did I ever feel that something within America was getting in the way of my dream. My adopted country was there to provide the opportunity, and it was up to me to seize it.

That idea best summarizes my love for this country: Everything was up to me. It was up to me to shape my work habits, my expertise, my networking and, ultimately, my destiny.

When I changed careers and graduated to my first love, journalism, I took my American dream to the next level. If I felt like writing a critique of our president in my weekly column, I never took it for granted that I lived in a country that afforded me that freedom.

This priceless freedom to shape one’s destiny infuses two new books connected to the iconic Michael Milken.

The first, “Witness to a Prosecution: The Myth of Michael Milken,” is a detailed, firsthand account by Richard Sandler of one the biggest news stories of the 1980s. Sandler, who is both a close friend of Milken’s and acted as one of his attorneys, describes the beginning of the long ordeal as follows:

The first, “Witness to a Prosecution: The Myth of Michael Milken,” is a detailed, firsthand account by Richard Sandler of one the biggest news stories of the 1980s. Sandler, who is both a close friend of Milken’s and acted as one of his attorneys, describes the beginning of the long ordeal as follows:

“In 1986, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the US Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York began an investigation of Michael and Drexel Burnham Lambert and its High Yield and Convertible Bond Department, a department Michael created and headed. Michael was the most successful and innovative financier of his time, and Drexel, due to Michael, was the most successful securities firm on Wall Street.”

That description gives us a little taste of a high-flying time in America that today feels almost quaint. These were the days before 9/11, the Iraq War, Donald Trump, COVID, Black Lives Matter, Twitter wars, cancel culture, remote work, AI and a national crisis of isolation and mental health.

Quaint or not, the American dream was as alive as ever during the roaring ’80s. Through his blow-by-blow account, Sandler chronicles not just a controversial prosecution but also the aphrodisiac of ambition and dreams that shapes the American story. There’s not much he didn’t see.

“From the moment the investigation started, I became Mike’s personal lawyer, responsible for working with the lawyers we hired and overseeing the defense,” Sandler writes. “As such, I witnessed exactly what happened, how it happened, and why it happened.

“Michael Milken and this prosecution have been described in books and articles by others who had no firsthand knowledge of the events and were motivated to describe what happened in a certain way. I, too, am motivated to describe what happened, but I am motivated because I want the true story told, and I do have firsthand knowledge. I lived this matter day in and day out for over 10 years.”

The book is a slice of heaven for finance and legal nerds. The amount of detail can be mind-numbing, but it’s clear that Sandler is injecting as much context as possible so readers can get a fuller picture of why Milken ended up pleading guilty to regulatory violations and serving time. It’s finally the moment, Sandler writes, “to set the record straight.”

Because I’m neither a finance nor a legal nerd — I’m more of a philosophy nerd — what fascinated me most about the book was a section explaining the infamous term “junk bonds,” which has long been associated with Milken.

It turns out the moniker “junk” is somewhat misleading. Technically, while higher-rated or investment-grade bonds have ratings such as AAA, AA or A, anything rated below BBB was more accurately called “high yield bonds” rather than “junk bonds.”

What was so special about these high yield bonds? As Sandler explains, “The rating agencies gave a rating based on the past. Michael did research to understand the future, where a particular company was going and where its industry was heading.”

Milken’s innovation, in other words, was to assess investment opportunities and yields based on future potential rather than just past performance, as everyone else was doing. I found that a compelling idea. You’re not a captive of your past; you’re a master of your future. But it required a lot more due diligence, which, as Sandler writes, “often included meeting the management of the company, since Michael believed the most valuable asset was human capital, and that was not on the balance sheet.”

This forging of human capital and future potential is what brought home the idea of the American dream. Milken was out to democratize capital and make it accessible to those who showed potential but didn’t meet the standards of the rating agencies. He wanted to help entrepreneurs with good ideas go after their dreams. Sandler quotes a Wall Street Journal op-ed from October 1990:

“[Milken] would in time conclude that what really counted was future cash flow and the quality of a firm’s management team. Mr. Milken helped raise funds for more than one thousand small firms, many of which have become household names such as MCI Communications, KinderCare and the Turner Broadcasting System.”

The fact that Milken’s innovation made him wealthy is a sign of his creativity and hard work more than anything else.

The fact that Milken’s innovation made him wealthy is a sign of his creativity and hard work more than anything else.

But as fate would have it, after he got through his legal ordeal, Milken’s own destiny was severely tested. He was diagnosed in 1993 with terminal prostate cancer and was told he had 12 to 18 months to live. This personal trauma brings us to the second Milken book I alluded to, this one written by Milken himself: “Faster Cures: Accelerating the Future of Health.”

Fueled by his will to overcome his cancer diagnosis and help others benefit from his work, Milken threw himself at the often dysfunctional and inefficient world of public health. The book is a deep dive into one man’s relentless passion to make a complex behemoth institution work better. Just as he disrupted the world of finance, Milken took that same discipline and innovation to the field of health. By connecting dots that were never connected and better leveraging resources and investments, he made enough of an impact that Fortune magazine dubbed him, “The man who changed medicine.” In the process, he managed to conquer his own cancer through the latest treatments and a radical change in his diet and health habits.

In both books, which cover a half-century of Milken’s life, we encounter a man whose nature is to aim as high as possible. If there is a golden thread to the man and his life, it may be just that: a drive to dream big and to act even bigger. The jacket description of “Faster Cures” speaks to an almost child-like enthusiasm to dream the biggest dreams:

“What if cleaning early-stage cancers from your body could become as routine as going to the dentist to clean your teeth, or if a single vaccine could protect you against multiple viruses, or if gene editing could eliminate many birth defects and slow the aging process?”

Milken wants us to know that these dreams, and many others, are within reach.

It’s perhaps fitting, then, that the culmination of Milken’s life centers around an expansive public space in Washington, D.C., named the Milken Center for Advancing the American Dream (MCAAD).

According to reports, he has poured $500 million of his own money into establishing the complex, which is currently being built and sits across the street from the U.S. Treasury and catty-corner from the White House.

For all the spectacular nature of his latest venture, in pitching the center on its website Milken prefers to focus on human interest stories.

“Over the past five decades,” he writes, “I’ve known and worked with many outstanding people who exemplified the American Dream. When we began planning the Milken Center for Advancing the American Dream several years ago, we wanted to celebrate their stories and those of thousands of others who provide inspiration and hope for the future.”

Among those stories, he describes people like:

• Reginald Lewis, who came from a tough East Baltimore neighborhood and through sheer grit became a star athlete, a Harvard-trained lawyer and a remarkably successful entrepreneur. It was my privilege to help finance the growth of the business that made Reg one of the first African-Americans to lead a billion-dollar enterprise.

• Yvonne Chan, a self-described “very poor peasant kid” who emigrated from China, followed her dream in Los Angeles and inspired thousands of inner-city students to excel beyond all expectations. As a young woman, she learned Spanish picking oranges and grapes to put herself through school. Today, 90% of the predominantly Latino students in the low-income neighborhood school she founded go on to college.

• Kevork Hovnanian, an Armenian Christian living in Iraq, who fled to America after the 1959 revolution with no money but with fierce determination. He went on to build one of the nation’s largest home-building companies. So strong was his feeling about keeping new houses within the reach of average Americans that he personally set the prices.

• Padmanee Sharma, M.D., Ph.D., whose ancestors were indentured laborers in India. Sold into slavery, they landed in Guyana on South America’s Atlantic coast. Today, in partnership with her husband, Nobel laureate James Allison, she advances the science of immunology at an Anderson Cancer Center laboratory.

In seeing these stories, I couldn’t help but think back to a tiny Arab village 20 minutes from Casablanca where I was born many moons ago. While hardly having the same level of drama or suffering, I still see myself as a product of the American dream: moving with my family to the frozen tundra of Montreal, falling in love with English, graduating from McGill, getting a first job with Procter and Gamble, moving to Los Angeles, opening my own ad firm, raising a family, starting a new career mid-life, etc.—and all along, struggling, losing and sometimes winning, but always fortunate to be in a place where there is “hope for the future.”

This hope now occupies Milken’s present. If he spent the ’80s selling America high yield bonds, he is now promoting high yield hope. It’s as if he wants “hope for the future” to spread like a positive epidemic, available to anyone willing to put in the work.

As it says on the MCAAD website, “The idea at the heart of the American Dream speaks to the aspirations of people everywhere: No matter who you are or where you come from, you should have the opportunity to build the life you want to live. Our purpose is to make the American Dream attainable for all.”

In addition to assembling a top professional team, Milken’s center has identified Four Pillars that help turn dreams into reality: Education and job training; good health; economic freedom; and an entrepreneurial mindset. You might say those four pillars have defined Milken’s professional life.

That professional life has seen many swings. Since he became such a household name in the ’80s, in recent years Milken has had a tendency to stay in the background and let his actions and initiatives, such as the prestigious Milken Institute Global Conference, do the talking.

I’ve only met him a few times, bumping into him at events or galas. One encounter that I distinctly remember occurred several years ago at Milken Community High School, where one of my kids was enrolled. He was wearing jeans and was about to go downtown to teach math to inner city kids. When I offered to tag along one day and write about it in my weekly column, he was polite but didn’t show much interest. Clearly, he wasn’t doing it for the press or for his image. He was doing it for the kids.

Maybe the fact that he wasn’t looking for press is what drew me to write about him. I would say, though, that the biggest reason is simply that I share his belief in the American dream. I’m still that grateful immigrant from Morocco who believes in such things. At a time when cynicism and political tribalism rule the national conversation, we could do worse than bring back the innocence of pursuing dreams.

What makes Milken especially effective as a dreamer is a knack for strategy and execution. I’ve spoken to several people close to him and they all say the same thing: He can cut through the bureaucracy and get big things done with maximum impact. He’s a dreamer with a plan. It’s not a coincidence that his center wants to advance the American dream, not just celebrate it.

Jews should know all about advancing dreams. Indeed, the Jewish story in America is very much one of pursuing dreams — for us and for others — and making them happen. Judaism at its best is when the Jewish people share their gifts with the world to make it a better place.

As Rabbi Marc Angel wrote in 2004 on the 350th anniversary of Congregation Shearith Israel in New York: “America is not merely a country, vast and powerful; America is an idea, a vision of life as it could be … During the past 350 years, the American Jewish community has accomplished much and contributed valiantly to all aspects of American life.”

Michael Milken, the financial genius of days long past, is sharing his gifts with the world to improve our health and help us follow our dreams. In doing so, he is fulfilling his own American dream.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.