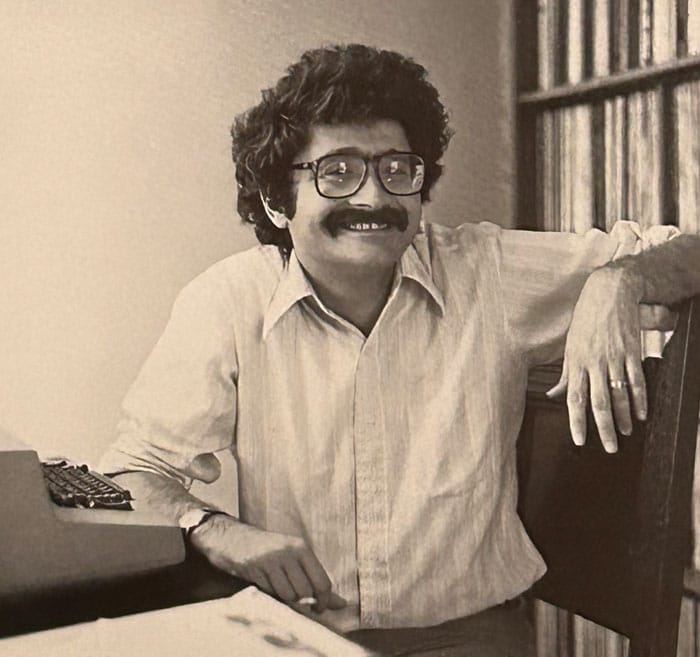

Dennis Fischer Photography

Dennis Fischer Photography It was Shabbat morning, and Rabbi Daniel Lapin and his friend Michael Medved were walking along Venice Beach. Even though it was raining, they didn’t mind.

Suddenly, they heard a man shouting at them. “A little old guy popped out of the doorway of this decrepit looking, rundown building and called to us with great urgency,” Lapin said. “He yelled, ‘We need you for a minyan!’”

The rabbi didn’t feel like going in – after all, he’d already davened back at his apartment that day. But Medved volunteered them, walking into the building with the old man, and Lapin followed.

“With us, they had exactly 10 men for the minyan,” said Lapin.

While praying, Lapin looked around: there were buckets all around to catch the rain leaking in through the holes in the roof. The lights were off. The youngest man there was in his ‘60s.

After services were over, Lapin and Medved learned that the old man who summoned them in was Mr. Winer, the president of the shul, and he asked what they were doing in Venice Beach.

“He said that he had grandchildren, and he knew that no young people were interested in Judaism anymore,” Lapin said. “Medved and I looked at each other, and I knew exactly what he was going to do. He said to old Mr. Winer, ‘If you make this man the rabbi of the shul, we will have the shul filled up with young people for Rosh Hashanah.’”

Mr. Winer told the young men how they couldn’t afford to hire a rabbi. They hadn’t even been able to pay the electricity bill, so the power got shut off at their shul, the Bay Cities Synagogue. The roof was in serious disrepair as well. “Because I was working for Merrill Lynch at the time, Michael felt safe saying to Mr. Winer that I would work for $1 or less per month,” Lapin said.

The rabbi went along with it and agreed on the salary. But first, before anything could be finalized, he had to meet the synagogue committee, made up of Mr. Winer and two other men his age. The three men huddled in a corner for a few minutes to talk while Lapin and Medved waited. Then, the old men came back to where Lapin and Medved were standing, and said they had to test the rabbi.

“One of them, Mr. Polsky, comes over and rattles off a verse which I vaguely recognized to be somewhere in the book of Isaiah,” Lapin said. “He asked me if I could say the next verse. This was so remote from the capabilities of a conventionally educated yeshiva guy that I had open mouth astonishment.”

The man kept rattling off verses, and Lapin got about a third of them right. At the end, Lapin told Medved he was sorry that he didn’t do very well on the test. “I was torn between disappointment and hilarity,” he said. After another huddle with the men in the corner, Mr. Winer came back with some good news. “You’re hired,” he told Lapin.

The rabbi accepted the job. And, of course, Medved turned out to be right: Lapin was going to breathe life into this shul and change hundreds of lives in a short matter of time.

The Jewish Community Along the Ocean

In the 1950s and ‘60s, Venice Beach and Santa Monica were home to a thriving and lively Jewish community. The neighborhood had around a dozen synagogues and a Jewish infrastructure that included the Israel Levin community center and kosher butchers and bakeries all along the Venice boardwalk. Some families lived in Venice and Santa Monica full time, while others had vacation bungalows there.

But then, in the mid-‘60s things began to change. The city of Santa Monica demolished the bungalows and put up two large condo buildings. The cost of housing — and just about everything else in the area — started going up. The kosher butchers and bakeries shut down. People moved out of the area. By the late ‘60s, only Mishkon Tephilo, a Conservative synagogue, and Bay Cities Synagogue, which was established in the late 1940s, remained open.

In the 1970s, after graduating from college, Medved moved to Venice and started becoming more interested in Jewish observance. He grew up in a Conservative home, and his family was part of Adat Shalom in West L.A. So when his uncle passed away and someone needed to say Kaddish, Medved started going to Mishkon Tephilo.

Medved, a writer, had just put out the acclaimed “What Really Happened to the Class of ’65?,” a book that featured interviews with 30 people from his graduating high school class at Palisades High School. This was one of the most privileged classes of students in American history; they came from wealthy families and had nicer cars than their teachers. Medved was curious to see how his classmates were doing 10 years down the line, and what he discovered was that many of them had gone through tragedy. Many didn’t have values or traditions they could fall back on when times got tough, and they were suffering.

The end of the book featured an interview with Medved and his wife, who said that they were going to be reexamining the faith of their grandparents. Along with other people their age, they were attending synagogue on a regular basis and learning about the Torah.

According to Lapin, at this time, some young people were disillusioned with the cultural shifts that had happened in the 1960s and ‘70s, including the Vietnam War and the hippie and drug movement which turned some youth away from getting married and having children.

“All of that led to an aftermath of alienated young Jews who were attracted to unvarnished authenticity,” said Lapin, who had picked up “What Really Happened to the Class of ’65?” in an airport and found the book to be fascinating.

Just a few months after reading it, by chance, Medved invited Lapin to speak at his shul on Shabbat. Right away, Medved recognized that Lapin, the son of the Chief Rabbi of Cape Town, South Africa Rabbi Avraham Hyam (A.H.) Lapin, was talented. “Rabbi Lapin was an extraordinarily gifted teacher,” he said.

The two became fast friends and immediately began studying Torah together. And just a few months later, when they were walking along the beach that Shabbat morning in 1978, the hand of God led them to the Bay Cities Synagogue.

Rebuilding the Shul

When Medved and Lapin stepped in to lead the shul, they updated the name to Pacific Jewish Center (PJC). Lapin taught several classes throughout the week, and hundreds of young people showed up.

One of those attendees was Jewish Journal contributor Judy Gruen, who started going to classes with her now-husband Jeff. Lapin was her first Torah teacher, and she said that she was, “alternately amazed, thrilled and sometimes alarmed by some of the things he said. They were radically different from anything I had ever heard before and challenged and expanded my thinking.”

Like nearly all the members of the PJC, Gruen was a baal teshuva who had not grown up in an Orthodox home. She wrote about this and her experience at the PJC in her book, “The Skeptic and the Rabbi: Falling in Love With Faith,” describing how much of an impact Lapin had on her spiritual growth. “Rabbi Lapin was tireless in helping us navigate all sorts of challenging situations arising from our religious commitment, particularly more complicated family dynamics,” she said. “I know from personal experience that he did so with sensitivity, creativity and respect for non-religious family members.”

Another former PJC member, Selwyn Gerber, who, like Lapin, is South African, served as the shul’s treasurer in the three years he was there.

“It was one of the most exciting spots in Jewish Los Angeles.” – Selwyn Gerber

“It was one of the most exciting spots in Jewish Los Angeles,” Gerber said. “Lapin made Torah comprehensible and easy to relate to. He’s a master teacher.”

Lapin and Medved worked together to figure out a model for the shul. They decided that instead of charging membership fees, they’d require members to participate in at least one weekly class instead. They didn’t charge for tickets for High Holy Day services, either, and found that members would voluntarily – and generously – donate to the shul. “Before there was Chabad in the neighborhood or Aish HaTorah in L.A., there was the PJC,” Medved said. “This was the first community where everyone was a baal teshuva.”

During the classes, Lapin would invite attendees to come to the shul on Shabbat. At the same time, Medved made a national announcement, encouraging people to show up. “I was a guest on ‘The Tonight Show’ because I was promoting one of my books, and I invited anyone who was interested to come to the PJC.”

The shul’s location also drew people, since it was so visible and accessible from the beach and boardwalk. That’s how member Elizabeth Danziger, who lives in Venice, happened to discover it. “I was passing by with the other people on the boardwalk,” she said. “I saw people gathered outside the shul on Shabbat. They seemed to be having a special experience. I passed by several times, and then I thought, “I could have that experience, too!’” On Shababt Shuvah in 1981, she went to the shul on Friday night. There, Medved greeted her, and she received an invitation to someone’s home for Shabbat dinner. “I kept coming back,” she said.

Because of the classes, national exposure and visibility in Venice, the shul became so packed that it was standing room only. “It filled up,” Lapin said. “We had to remodel the inside to add more seats.” The synagogue was full not only for Rosh Hashanah and the rest of the High Holy Days, but all year long.

“A year-and-a-half after we met, Mr. Winer reveled in giving weekly Shabbat announcements as the undisputed president of the synagogue,” Lapin said. “I got a raise and started earning $2 a month.” Many of the men and women in the classes were either dating or started dating through the shul; in a few years, Lapin had married 70 couples. The rabbi met Susan, the woman who was to become his wife, after she came for Friday night services. “We got engaged 12 days later,” he said.

When all the newlyweds started having children, they established a school called the Emanuel Streisand School of the Pacific Jewish Center, named after Barbara Streisand’s father, who’d worked as a school superintendent. The singer had held her son’s bar mitzvah at the PJC. The men at the shul started a baseball team cheekily called the “Elders of Zion,” and the community was known for its bustling Hanukkah parties. “PJC was dynamic, [and] a young and enthusiastic baal teshuva community anchored by exciting Torah learning,” said Gruen. “It also had a bit of a countercultural allure of being off the beaten track.”

For many years, the shul continued to grow. But when the school, renamed Ohr Eliyahu, moved closer to the Pico-Robertson community, it was difficult for parents to drive back and forth from Venice every day. During the mid- to late-‘90s, many of them began to move to Pico-Robertson or La Brea – where Ohr Eliyahu eventually settled and remains today – so they could be closer to the school as well as part of the larger Jewish community. “Some were just tired of the druggie-homeless problems along the boardwalk outside of our shul,” Gruen said. “We moved for these reasons and for our kids to have a broader network of friends. As much as we were grateful to the community for all it had given us, it was changing and we needed to move on.”

In 1992, Lapin left PJC and moved to Mercer Island in Seattle; four years later, Medved joined him. Over the next few decades, the shul’s membership continued to dwindle, while Venice became increasingly expensive and plagued with problems: homelessness, drugs and crime. Chabad opened up in the area, and some members went there or joined breakaway minyans closer to their homes. While there was an eruv that would allow people to carry on Shabbat in Santa Monica, it didn’t last. This meant that mothers and fathers who wanted to push children in strollers couldn’t attend services on Shabbat, a deal breaker for young families.

Still, some people, including Elizabeth Danziger and her husband Alan, stayed. They enjoyed being near the beach and in this unique community. And, after all these years, they say that the welcoming spirit of the shul remains the same.

Revitalizing the Shul

Since Lapin left, the shul has hired different rabbis to lead it. Currently, Rabbi Shalom Rubanowitz, a longtime friend of Medved, is serving as the rabbi. He’s been with PJC, which is now called The Shul on the Beach, since 2015, and is appealing to a mixed group of Jews who happen upon the shul. There are the “old timers” and core members like the Danzigers, along with singles, converts, baal teshuvas and young people who had a religious upbringing but are not currently observant. “There are a number of Jews in their late teens to early 20s who grew up Orthodox on the east coast, became disenfranchised, ended up in Venice and at some rehab centers nearby and come to our shul,” Rubanowitz said. “They love it. We have a growing group of these kids, which is a new phenomenon. I’m proud of that. That’s a big area of Jewish life that sometimes gets neglected.”

Much like the shul in its heyday, Rubanowitz and the current members are offering diverse programming to appeal to the different people in the community. On Wednesdays, he holds Town Hall, which is a class for people to learn about Judaism. The class, which has been sanctioned by two beit dins, can be counted towards learning for converts.

“We are an introductory class on Judaism,” Rubanowitz said. “We’re a source of information for people who are new to Judaism, whether they grew up Jewish or not.”

The Shul on the Beach hosts Shabbat Lounge, a singles event that features sushi and sake, as well as parties for Purim and Hanukkah and community meals on Friday nights. Of course, there are services on Shabbat and the holidays. Right now, Rubanowitz is hoping to expand the physical building and have housing for people, weekend rentals and facilities for weddings and bar/bat mitzvahs.

While Venice still has a large homeless population, Rubanowitz said that post-COVID, it’s gotten better. If someone doesn’t feel comfortable walking home after a Friday night dinner, a member of the shul will accompany them. Plus, the shul makes it their mission to help the homeless community around them too.

“When we have leftover food on Shabbos, we aren’t afraid to approach the homeless and give it to them,” the rabbi said. “When there are some potentially dangerous situations, the homeless people we helped will watch our back and protect us. Our chesed, our kindness, has made us part of the boardwalk, as opposed to strangers or opposites.”

Going forward, Rubanowitz hopes that the community will be able to put up an eruv and attract young families again. But in the meantime, he’s focusing on the Jews of all different backgrounds who like the unique nature of the community. “They’re eclectic,” he said. “I’m kind of eclectic too, and I think that’s a good thing.”

It’s clear that this unique synagogue, in all of its incarnations – Bay Cities, PJC and Shul on the Beach – has been an important part of the history of Jewish Los Angeles.

It’s clear that this unique synagogue, in all of its incarnations – Bay Cities, PJC and Shul on the Beach – has been an important part of the history of Jewish Los Angeles. Rubanowitz, as well as the shul’s members, are optimistic about its future and how it continues to serve a dynamic group of people in the area. Alan Danziger, Elizabeth’s husband, who has been a member of the shul for nearly four decades and served as its latest president, raised his kids in Venice and now is a grandfather. He said that throughout all the changes over the years, the Shul on the Beach is “still a very warm and hospitable place. It is still a unique venue with its own attraction. I would like it to continue to be a place that welcomes people, but with the fire of a community looking out for each other.”

“People feel comfortable walking into our shul and immediately feel welcomed and at home. We hope to continue that spirit.” – Elizabeth Danziger

Elizabeth echoed a similar sentiment. “Although we are Orthodox, we are unusually inclusive and eclectic, welcoming Jews of all backgrounds and philosophies,” she said. “We have kept the shul open all these years so that when a person feels the urge to return to Judaism, he or she does not have to face the hurdle of walking into a sea of black hats … People feel comfortable walking into our shul and immediately feel welcomed and at home. We hope to continue that spirit.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.