Vintage postcard: DenKuvaiev/Getty Images

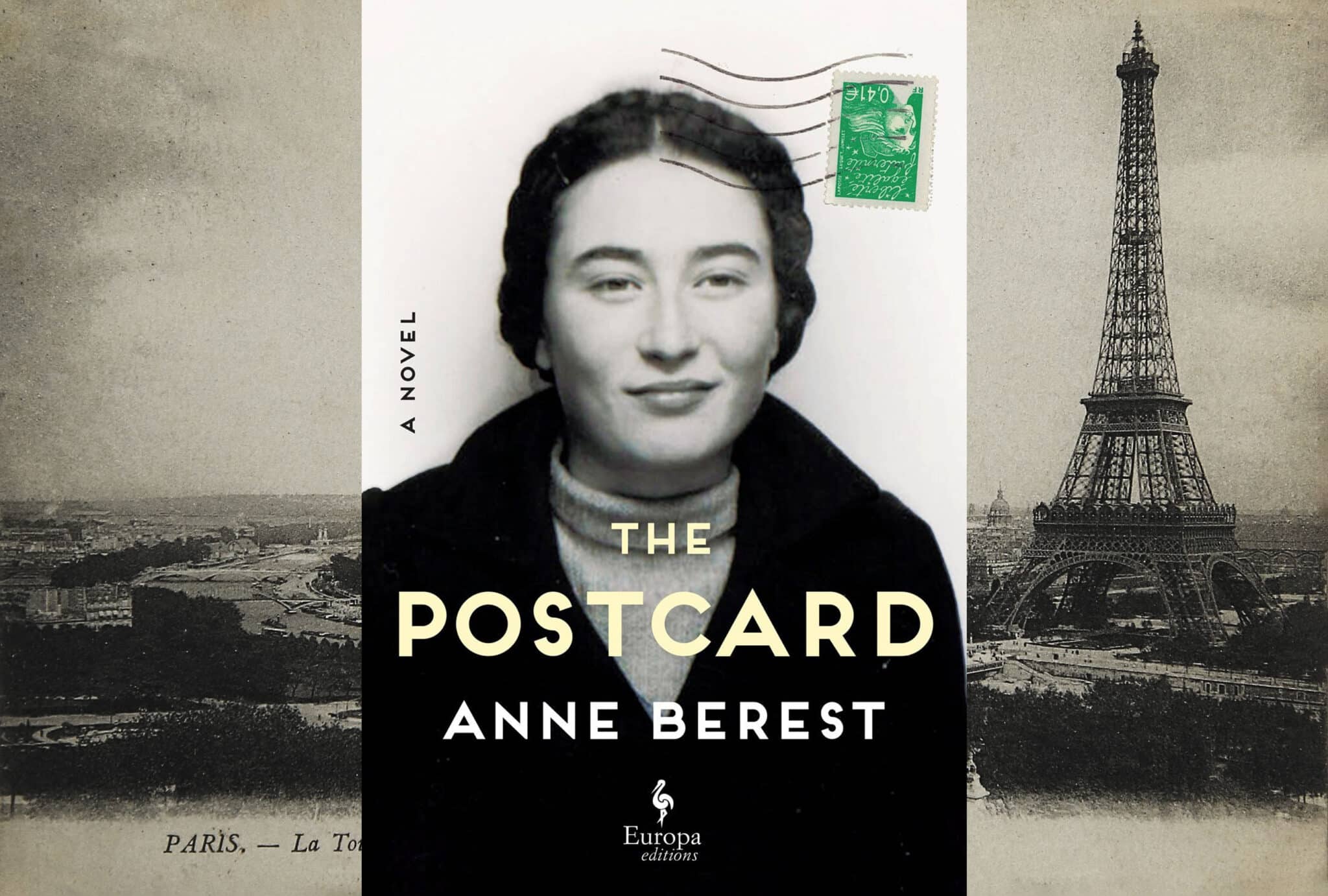

Vintage postcard: DenKuvaiev/Getty Images Just when I thought I couldn’t bear another Holocaust book, movie or museum, French author Anne Berest’s autobiographical novel “The Postcard” (Europa Editions) held me hostage for a mesmerizing week in May. The granddaughter of a survivor who was the only family member to escape the Holocaust, Berest weaves her personal quest for identity in 21st-century Paris into the buried history of her Russian/French/Jewish family from the Russian Revolution to the aftermath of World War II.

The straightforward mystery plot kicks off with the author’s discovery of an anonymous postcard that her mother had hidden years ago. It contains only the first names of lost family members and is post-marked the Louvre. “Who would send such a card, and why?” wonders the third-generation granddaughter, looking for clues to her lost ancestors. Her mother Léila is in no rush to find out.

But she joins her daughter’s search, poring over records that ultimately take them back to the village where the family thought they were safe as they awaited their French citizenship. Eventually Anne tracks down the descendants of the neighbors who had identified her family for deportation. With research so thorough that it took the author ten years to write, the result is a brilliant hybrid—a memoir/novel that compares to Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” and Irène Némirovsky’s “Suite Française” in its evocative power.

Berest pulls us forward with scene after powerful scene depicting life in a war zone. She imagines her grandmother’s life on the run and in the Resistance. She captures the randomness of becoming a victim, the psychological aftermath for survivors, and the scars that pass through the bloodstream. As Léila reminds her 40-year-old daughter, “If we had been born in that era, we too could have been transformed into buttons.”

Like Madeleine Albright and many others, the 40-year-old author was raised without knowledge of her Judaism. Her parents identified as Marxists in a restructured France where laïcité—an official doctrine that separates church and state—was the rule. In Paris, it is still recommended that Jewish children not wear yarmulkas and that Muslims not wear hijabs outside of the home. “Don’t look back,” was the unspoken message after the war as the French systematically swept under the rug their complicity in meeting quotas for delivering Jews to the camps—numbers that are still being disputed today.

Two incidents motivated prize-winning author and screenwriter Berest to keep searching for her roots. Her 10-year-old daughter came home from public school one day and asked, “Are we Jewish?” She was curious because classmates had told her, “We don’t really like Jews here.”

Another time, a man she was dating invited her to a seder where she did not know any of the Passover rituals. When another guest accuses her of being a Jew of convenience she confronts a common dilemma, “What does it mean to be a Jew sans synagogue?” In midlife, she confronts the role that prior family trauma has played in her own life. “It is in my DNA,” she realizes, regarding inexplicable emotional pain she often suffers.

While reading Berest’s book, I recognized the similarities with my own family’s story. Having grown up in the post-war years in the Bronx, I know almost nothing about my grandparents’ lives in Europe, including where they came from. Poland, Russia and Belarus are a few possibilities. As a child, I created a vague family story. My grandparents left Poland for the U.S. in the early-20th century, settled in New York, changed their names and built a new life.

Having grown up in the post-war years in the Bronx, I know almost nothing about my grandparents’ lives in Europe, including where they came from.

It was understood that for my grandparents, there were no “good old days” back in the old country—thus there was no reminiscing. Fleeing, or course, is not the same as relocating. In grade school when we were doing reports on family histories, I got a chance to interview my maternal grandfather. “Why did you come to America?” I asked him in 1958. “The streets were paved with gold,” he laughed—signaling that the interview was over.

Meanwhile, in my parents’ home where they were obsessed with documentary footage of the war and the soundtrack from “Fiddler.” Certain words like refugees were whispered—or spoken only in Yiddish. Why the butcher had numbers on his arm, my mother’s confusion about her birth date, who I was named for, why my grandmother never left the house, and neighbors who kept their apartments dark were not discussed. To make their break with the past complete my parents dropped lighting candles, praying and membership in a synagogue. Like the patriarch Ephraim in “The Postcard,” they wanted to be Americans first.

Looking back, I realize that it was only at important family events like funerals, weddings, and Bar Mitzvahs that they leaned on the rituals. When my father died young we sat hardcore shiva for a week—covered mirrors, hard wooden benches, friends and family feeding us brisket and roast chicken. Back in the day, Jews knew how to grieve. They also knew how to fly through the air like acrobats while performing wild Russian kazotzkys and mind-bending horas at weddings. Our family affairs looked nothing like the sitcoms I was watching on TV.

Many years later, my husband and I were so well assimilated that both our kids argued against having a Bar Mitzvah. We insisted that since they were Jewish on both sides they should get a Jewish education followed by a big 13th birthday party. They went along to placate us because they were good kids. Now I can see shades of our heritage in their striving and storytelling that they don’t even see. As for the next generation, I wonder what form my grandchildren’s Jewishness will take without religion or the warmth of a big extended family. Recently I dug out the Jewish star I was given as a girl and started wearing it again as a reminder of where I came from. And who I am.

Without a doubt, “The Postcard” is not an easy read. Parallels with the rise of authoritarianism, propaganda and antisemitism in today’s United States are chilling. A few times I felt that the book was too sad to keep reading. But whenever I put it down, I was pulled back by the sheer strength of Berest’s storytelling. Her ability to conjure real people in surreal circumstances while digging deeply into her own psyche is profound. My understanding of that time and my post-war family’s reaction to it runs deeper as a result.

Los Angeles food writer Helene Siegel is the author of 40 cookbooks, including the “Totally Cookbook” series and “Pure Chocolate.” She runs the Pastry Session blog.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.