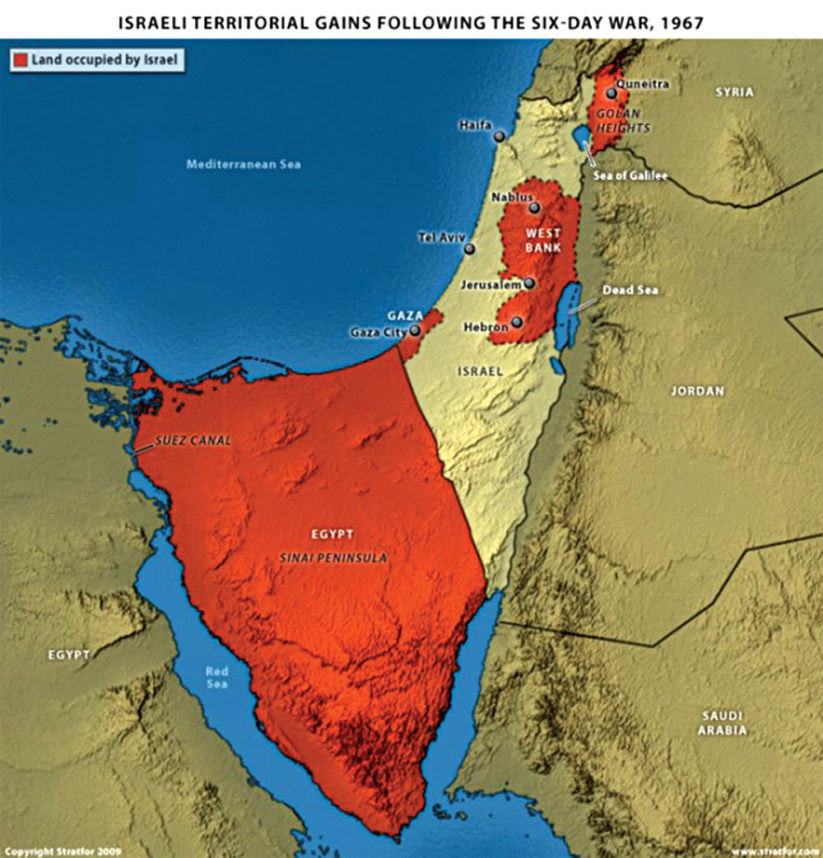

It was a war the world had never seen — pre-emptive, daring, lightning fast. In six days — 132 hours — one small army defeated five. By the last day, Israel had captured territories four times its former size. The war changed the map of the Middle East — of the world — in ways so profound, from Washington to Cairo, from the United Nations to The Hague, from college campuses to refugee camps, that the fight over the spoils of that conflict continue.

The war that began June 5, 1967, ushered in decades of deep American diplomatic, economic and military engagement in Israel, and introduced a new vocabulary into the news — terror, Islamic fundamentalism, Messianism, suicide bombers, hijacking, refugees, Palestine.

This year, the 50th anniversary of that war, its consequences linger. Israel’s stunning victory swung America firmly to its side, jump-starting a special relationship that includes billions of dollars in foreign aid and unprecedented security cooperation — a bond that affects every American soldier, diplomat and taxpayer.

Israel’s continued control over some of the territories captured in that war and of their inhabitants is still a flashpoint of international controversy and a source of deep moral and strategic disagreement among Jews themselves. Many Jews and Christians who explain the sudden victory as the hand of God fiercely resist any peace that requires the return of biblical lands. Others fear that in Israel’s victory lay the seeds of its own demise if the result is that Israel ceases to be a Jewish, democratic state.

[TIMELINE: The six days of war]

Meanwhile, writes Said K. Aburish in his 2004 book, “Nasser: The Last Arab” (St. Martin’s Press), the Six-Day War “was so unexpected in its totality, stunning in its proportion, and soul-destroying in its impact that it will be remembered as the greatest defeat of the Arabs in the twentieth century. The Arabs are still undergoing a slow process of political, psychological, and sociological recovery. It is easy to trace all that afflicts the Arab world today to the defeat which the 1967 War produced.”

Millions of Arabs lost faith in their secular leaders and turned to fundamentalist Islam. The Palestinians realized they couldn’t rely on conventional Arab armies to beat Israel and pinned their hopes instead on a man named Yasser Arafat —and so the age of modern terrorism was born.

You have to read only the headlines any given week to understand that while Vietnam is history, the Six-Day War is current events.

The Arabs refer to the war as the naxa, or setback. The victors christened it the Six-Day War. Neither name gets it right. “Setback” is an epic understatement, like calling a scalping a haircut. And although “Six-Day War” deliberately echoes the biblical Creation story, it obscures one of the most important facets of the war itself: the very reason why Israel won.

The outcome of the war was decided in its opening hours. Israeli warplanes took to the skies in the early morning of June 5 and headed on a stealth mission toward Egypt. They flew just a few meters above the Mediterranean Sea to avoid radar. They banked toward land, fanned out over dozens of airfields, rose and then dived down to unleash a hellfire of cannon fire and bombs on their targets. All of Egypt’s airfields were rendered useless, and most Egyptian aircraft were destroyed. Israeli planes then decimated the Syrian, Jordanian and Iraqi air forces. Within two hours, in three waves of attacks, Israel had destroyed 452 enemy airplanes. It had complete control of the skies.

The attack began at 7:45 am. By 10:30 a.m., air force commander Gen. Motti Hod turned to Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin and reported, “The Egyptian air force has ceased to exist as an effective fighting force.”

The Six-Day War was a victory of intelligence over firepower, of preparation over bluster, brains over brawn. It was a triumph of foresight and planning, the vision of the few that set in motion the bravery of many. In that sense, one of the real heroes of the war — the most crucial and the least known — was a 20-something air force navigator named Capt. Rafi Sivron. Long before the first shot was fired, Sivron and his immediate superior, Lt. Col. Jacob “Yak” Nevo, created the plan that won Israel the war. They were the men behind Operation Focus.

In most books and articles about the war, stuffed with the exploits of generals, soldiers and politicians, Sivron and Nevo make cameo appearances — if at all. In the cataclysmic drama of those six days, there indeed may have been bigger actors, producers and directors — but those two wrote the script.

In January 2014, while I was working on a project about the war, I asked Uri Dromi, a journalist, Journal contributor and former Israel Defense Forces helicopter pilot, if he knew anyone who fought in it.

“Have you heard of Operation Focus?” he said.

“Of course.”

“Well, that was Rafi.”

I immediately dialed the number Uri gave me.

Rafi’s voice was strong, with a pleasant Israeli accent and precise English diction. As I was to learn over hours of conversation, in all things he did, Sivron was nothing if not precise.

Rafael Sivron was born in Haifa, the son of German immigrants who moved to pre-state Palestine from Berlin in 1934. His father’s parents remained in Germany. They were murdered in Terezin.

Sivron joined the Israeli Air Force (IAF) in 1954. He excelled as a navigator, flying missions in a variety of aircraft and helicopters. In 1962, at a NATO school for anti-submarine warfare in Malta, he met Nevo.

In the cockpit of a combat jet, Nevo was without equal, “the father of Israeli aerial combat,” in the words of IAF historian Iftach Spector. Nevo pioneered IAF dogfighting techniques, pushing himself and his planes to the limits.

Despite very different styles, the two bonded. Nevo was slight, thin — cockpit-sized. He also was serious and reclusive.

Sivron was movie-star handsome and far more outgoing. He prodded Nevo to have fun, which for Sivron meant taking breaks for tennis, attending the opera and playing “almost professional” classical piano.

Back in Israel, the head of the air force, Ezer Weizman, had long held that Israel’s best chance for winning the next war would be to destroy enemy air forces on the ground. The logic was sound, but there was no plan to carry out what other military leaders thought was a strategic fantasy.

Toward the end of 1962, Weizman tapped Nevo to come up with a plan, and Nevo remembered Sivron from Malta. By then, Sivron headed the air force subsection for operational planning, figuring the life-and-death logistics for Israel’s frequent counterattacks, stealth missions and patrols.

“When I say I was the head of this section, you could have in mind that I have something like 20 to 30 people working for me — maybe it is today this way. But then I was all alone,” Sivron said.

Nevo asked Sivron to design an attack plan. Sivron said he was too busy.

“You know what?” Nevo said. “There’s no war on the way, so pick a time. If you want to take three months, take three months. If you want to take three years, take three years.”

Sivron agreed. He was just shy of his 27th birthday.

As a present to himself, Sivron asked a friend returning from Italy to bring back an elegant fountain pen like the one he saw advertised in glossy magazines. Though he couldn’t really afford it, Sivron splurged on the pen, a Parker 61.

In a plain, three-story building in central Tel Aviv, in a tiny room at the end of a long corridor, Sivron sat alone at his desk, with that Parker pen, designing Operation Focus.

In the pre-planning stage, Sivron and Nevo brainstormed ideas for their plan, often bringing in experts from other departments. That’s when they came up with their first good idea: concentrate on the runways.

Gen. Hod had long said that a fighter jet is the most dangerous weapon in the world when it is in the air, but on the ground, it is useless. Nevo and Sivron figured if Israeli jets simply destroyed enemy planes, new ones could always arrive and take off. But without runways, nothing could get airborne.

“So this was decided, and I got an open hand of how to do it,” Sivron told me. “At this time, the Egyptians, Syrians and the Jordanians had about 20 military airports with 55 runways. So it was a problem, of course.”

In Hebrew, German Jews are called yekkes — a word that connotes extreme punctuality and exasperating attention to detail. Nevo, the pilot, left the operational details to Sivron.

“I was the yekke,” Sivron said.

Sivron focused first on the runways.

“You can’t attack airports if you don’t know where they are,” he said, “if you don’t know how they look, if you don’t have a picture, if you don’t know which aircraft.”

Reconnaissance photos provided Sivron with up-to-date knowledge of the enemy airfields. Israeli spies embedded in the highest echelons of Syrian and Egyptian society transmitted more details. Sivron learned the thickness of each runway, the type and parked position of each airplane, the patrol times and break times for each squadron, the distance each radar worked, the number of anti-aircraft guns.

Every detail mattered. Sivron learned that while Israeli jets used high-pressure tires, the MiGs that the enemy air forces flew used low-pressure tires. If you bombed a runway with normal bombs, ground crews could just fill it with sand and planes still could take off. The IAF outfitted their Mirages with two 500 Kgs bombs. All the bombs were fitted with innovative fuses that changed the timing of the detonators in order to afflict maximum damage on concrete runways.

Knowing where Egyptian observation posts were stationed enabled Sivron to design flight paths to avoid them. He matched the number of runways with the number and type of planes necessary to take them out, the altitude at which they needed to climb on approach, the angle at which they needed to attack, the possible effects of dust and wind, the number, weight and power of bombs each pilot needed to carry, how low and fast each plane could fly to avoid radar.

“When you fly a Mirage at 450 knots,” Sivron said, “if the sea is calm you have no ability to realize at what altitude you are. You can easily drop to the water. If you hit the water, it is your last flight.”

Nevo led endless test missions and bombing runs over mock-ups of Egyptian air bases in the Negev, feeding data back to Sivron, who sat at his desk, crossing out old vectors, calculating the timing anew.

Because the Arabs had so many more planes than the Israelis, Sivron and Nevo were counting on another ability the IAF had been developing for several years: shaving the time it took for a plane to land, refuel, reload, and get back in the air.

“For several years, squadrons used to compete as to who will do the turnaround quicker,” Sivron said. “These turnarounds in competition were made with substantial effort involving one aircraft at a time, almost laboratory-like conditions.”

With limited ground crews and the large number of jets involved in Operation Focus, the Israelis planned on a turnaround time of 20 minutes. Not as fast as seven, but still six times faster than the best the Egyptians could do. The Israelis would make up in flight time what they lacked in hardware.

Still, Operation Focus demanded that almost every Israeli combat plane and bomber go on the attack. Twelve would be left to defend the homeland.

“It was not an easy decision,” Sivron said. “People say it was self-explanatory. It was not at all.”

I asked Sivron how much help he had in figuring it out.

“I was alone,” he said. “Alone with myself. Nobody else was involved in this.”

Two years after he began his work, Sivron wrote his last calculation with the same Parker 61 he started with. As he finished the last line, the pen topped working.

The master plan for Operation Focus was printed and bound in an almost 60-page blue-covered booklet. Sivron wrote the main body of the order, which described the method and principles of Moked. Of the six appendices, Sivron wrote the two main ones, “Forces and Tasks” and “Routing.”

A meeting of senior brass went over the plan, line by line. They didn’t make a single change. From the first draft it was called Moked, Focus. The finalized order was passed on to the squadron leaders, base commanders and head of departments at the headquarters of the IAF. This was in September 1965.

Each top secret copy was numbered; each number was logged to its owner. Sivron, who by then had been promoted to major, was not given one.

“I could take it only to one place,” he said, “and that’s to prison.”

Sivron began studying economics and Middle East history at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

That summer, Lt. Col. Yoash Tzidon, the head of the IAF’s armament development section, decided to run Operation Focus through a newly acquired machine called a computer. By then, Hod had replaced Weizman as air force commander. Based on the likelihood of navigation problems, early detection, fog, wind and anti-aircraft fire, the computer determined that the chance of Operation Focus succeeding was 7 percent.

Sivron was unfazed. He had total confidence in his plan, and the data and calculations behind it. But the final decision rested with Hod.

“He was not an intellectual person,” Sivron said of Hod. “He was a farmer with a very straight way of thinking. Hod turned to Tzidon, ‘You know this is the best plan we have. If you want to make another one, go ahead.’”

The computer lost.

A year later, as tensions mounted between Egypt and Israel, Rafi Harlev, the head of the IAF operations, called a meeting of all squadron leaders.

“We have a plan,” he told them. “It’s over a year old.”

He passed out copies of Operation Focus for review and debate.

Again, there was not a single change.

In the popular imagination, the Six-Day War is a modern-day David and Goliath story. Just by the math, Israel truly was David. The Arab armies had more than twice the number of troops, and more than three times the number of combat aircraft and tanks. The Egyptians and Syrians were backed by Soviet weaponry and advisers — who could join their side at any moment.

But even though Israel was outnumbered on paper, it had advantages David couldn’t imagine. The Israel Defense Forces was the best trained, most professional and most highly motivated army in the Middle East. It was designed to defend the country. It had (and has) nuclear weapons.

The Arab armed forces, meanwhile, were designed to quell internal dissent and prop up unpopular regimes. In his new book, “The Six-Day War” (Yale University Press), Guy Laron reports a 1961 conversation between the Israeli spy Wolfgang Lutz (who fed intelligence to Sivron) and Egyptian Gen. Abd al-Salam Suleiman, whom Lutz had first plied with whiskey.

“We [in Egypt] have enough military equipment to conquer the whole Middle East, but equipment isn’t everything,” Suleiman said. “The army right now — in terms of training, military competence and logistics — will not be able to win a battle against a fart in a paper bag.”

As war appeared imminent, the CIA informed President Lyndon Johnson that should hostilities break out, Israel would win in 12 days. But though the Americans and even the Israeli high command were confident of eventual victory, the Jewish state’s leaders were wracked with concern that the casualties Israel would suffer would be devastating.

Israeli Prime Minister Levi Eshkol gave voice to that fear. At a cabinet meeting on the eve of war, he said, in Yiddish, “Blut vet sich giessen vie vasser.” Blood will run like water.

Israel’s best hope to ensure victory at an acceptable cost was a pre-emptive strike. It was Operation Focus.

Three weeks before the war started, Sivron donned his uniform and left his dorm room for IAF operations headquarters, where he was assigned to plan combined operations. By then, he was married, and he felt keenly what failure would mean: that his young family would be slaughtered like his paternal grandparents.

Weizmann had been pleading with Eshkol to implement Moked, in which he had complete confidence. On June 4, Eshkol, after receiving what he felt was a “yellow light” from the Americans, agreed.

On June 5, a fleet of Israeli planes took off after dawn.

In the central control and command room of the IAF, Sivron followed the take off and flight path of the armada he had planned.

Equally both tense and thrilled, he knew that if the Egyptians detected a single Israeli plane, the surprise attack could end in disaster.

Sivron watched as the majority of jets reached the “pull up point,” when they leapt from their low altitude sneak attack to enable their bombing run. It was still two full minutes before the first bomb had been dropped.

“I turned around and said, ‘We have won the war.’”

For Rafi Sivron, the Six Day War ended two minutes before it started.

The Israeli jets roared up on the Egyptian bases undetected — Yak Nevo’s among them. Many of the Egyptian pilots were eating breakfast when their planes and runways went up in smoke. Each wave brought more success. Soon after the first Israeli planes returned to base, it became clear to the air force that the plan had exceeded even its own expectations. Sivron was relieved, but not surprised. Focus worked.

I asked Sivron what he made of the success.

“Moked wasn’t worth anything without the pilots and crews and all the members of the air force,” he said. “We lost 24 pilots.”

The war would rage on for five more days. There would be tough, costly ground battles for Gaza, the Sinai, Jerusalem and the Golan Heights. All of them would have been immensely more difficult if Israel hadn’t gained control of the air.

As historian and Israel’s former Ambassador to the United States Michael Oren pointed out in his essential history, Six Day War, Egypt still could have stalled or even reversed Israeli gains on the ground. Victory still depended on many things: the pilots and soldiers, their commanders, the unity of the entire country, as well as Egyptian miscalculation.

But it is impossible to imagine Israeli victory without the plan. It wouldn’t have been a movie without a script.

For Sivron, too, the war continued. On Day Two, June 6, Sivron, who was still responsible for combined operations, joined his helicopter squadron as a pilot to carry troops over Saudi Arabian territory to land them in Sharm-El-Sheik, in the Sinai peninsula.

On June 10, he was at the front command post of the IAF in the southern Galilee, part of two squadrons of helicopters gathered in order to prepare a massive troop landing in the southern Golan Heights. Sivron was assigned to remain at the command post. Instead, he decided to join as a co-pilot in leading the landing.

In the second run, his squadron landed 20 troops some 30 kilometers ahead of advancing Israeli ground troops. The crossroad where they landed, called Butmia in Arabic but since renamed Rafid in Hebrew, remains until today the easternmost point of the border between Israel and Syria. It was 1 PM on the sixth day of the war.

A day later, Sivron piloted a helicopter to the Golan to evacuate a wounded officer. He returned in a Jeep ahead of advancing Israeli tanks, meeting with U.N. officials and Syrian prisoners. By 3 p.m. on June 11, the war was officially over.

“All of it was in our hands,” Sivron said.

One day after the cease-fire, Rafi Sivron entered the offices of air force operations HQ. Nobody was there. Everyone had gone out to celebrate.

Sivron took a car and a friend and drove for 24 hours, all through the Sinai desert to the Suez Canal.

“Everything was still burning,” he said. “Hundreds of tanks beside the road, dead soldiers. Then we went to Jerusalem, to the Western Wall.”

One week later, he was back at the university, studying.

Yak Nevo retired as a colonel from the Israeli air force in the late 1970s. He tried to set up a business but was unsuccessful. He turned to woodcarving and died in relative obscurity in 1989, of multiple organ failure, at the age of 55.

Sivron went on to serve in the air force until 1981, including a stint as defense attaché in the United Kingdom and Scandinavia. He retired as a brigadier general. Later, after a dozen years as El Al Airlines’ director of operations control and planning, he retired in 2000.

He lives in Tel Aviv with his second wife. From both marriages, he has five children, nine grandchildren and one great-granddaughter.

“Now I am playing tennis five times a week,” he said, “which keeps me young.”

Sivron is 81. I remarked how astounding it is that much of his country’s fate rested in his hands when he was only 27.

“This is the reason that I can talk to you now,” he pointed out to me. “If I were 37 then, maybe we wouldn’t be talking.”

In hindsight, it’s easy to see how the astounding victory of the Six-Day War, like any solution, created a slew of new problems. At the time the fighting raged, though, none of these were apparent, or mattered. Israel faced imminent attack by five Arab armies. If it lost, the country would be obliterated. That’s what the Arab leaders were saying, and 22 years after the Holocaust, Israelis were inclined to believe them.

“The only thing worse than a great victory,” Eshkol, the Israeli prime minister, said at the war’s end, “is a great defeat.”t

When all sides were locked in an existential confrontation, Israel’s reasons and objectives were clear and unambiguous. Rafi Sivron knew why he was fighting and what winning looked like. When you know those two things, it’s a lot easier to figure out how to win.

We Americans have grown resigned to endless wars and ambiguous outcomes. The wars in Vietnam and Korea ended in evacuation instead of victory. We still are mired in Syria and Iraq, fighting ISIS, the dregs of the Iraq War. American troops are still in Afghanistan, 16 years after 9/11.

If there’s a lesson in Operation Focus, it’s embedded in the very name: If you must go to war, concentrate on what you’re fighting for, and how to win.

And if you really think wars are won in only six days, or by some act of divine intervention, think again.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.