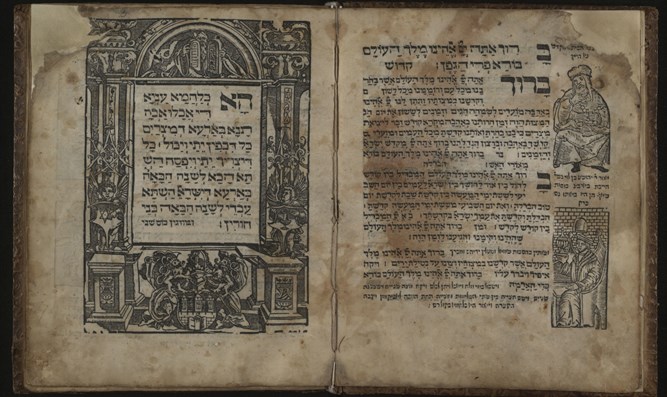

PASSOVER 5778, HAGGADAH:

“This is the bread of affliction that our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt. Let all who are hungry come and eat. Let all who are in need come and share the Passover meal. Now we are here; next year, in the land of Israel. Now we are still slaves. Next year, free people.”

Rabbi Denise L. Eger

Congregation Kol Ami

Our Passover story invites us to imagine that we are slaves longing for freedom. The seder meal teaches us to taste the bitterness of servitude in the maror and to see in the shankbone the hand of the Holy One lifting us from Egyptian bondage. We are the slaves. And yet we know we are not slaves. We eat a lavish banquet meal. We have the luxury of time to linger and discuss and drink plenty of wine even as we lean to the left, signifying that we are already free, already people of means. Slaves have none of this.

We repeat and learn and study the narrative of our ancient slavery in order to remember what it was like to be powerless and impoverished, even as we have climbed up the ladder of success. The narrative we recite teaches us that we can’t simply ignore those who in our own day and time struggle to be free and to find their economic footing. Passover is meant to teach us that God passed over the houses of the Israelites but we are not to pass over those who struggle in society: the homeless, the refugee, the undocumented worker, the stranger in our midst. Pharaoh hardened his heart. We must not harden our hearts. We must see them and invite them to share in our table. Passover is our wake-up call. Shake off your indifference to those without. Let all who are hungry come and eat. The time is now.

Rabbi Yosef Kanefsky

B’nai David–Judea Congregation

A commentary known as Hemdat Yisrael:

“I will add my piece to the generations of commentary before me. To me, these words are directed toward those who libel us, saying that we use the blood of Christian children when we knead our matzah, a libel that has done more harm to us than any of the decrees throughout time.

“This is the bread of affliction: it is poor man’s bread, with nothing in it other than flour and water! That our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt: long before Christianity was founded. Let all who are hungry come and eat: Non-Jews as well may join us in our Seder meal. Let all who are in need of investigating how we prepare our matzot come and share the Passover meal and taste the Matzah for themselves! Now we are here. But our holy prophets have promised us that in the future, God will turn the heart of the nations so that they all recognize the God of Israel, and they will be ashamed of their past behavior. Next year then, in the land of Israel!”

What is this bread that we eat? It is the matzo that every past generation of Jews has eaten. Living in as blessed a time in Jewish history as we are, the matzo is the centerpiece of family celebration, amid prosperity, security and a Jewish state that the author of Hemdat Yisrael could only painfully yearn for. But the matzo bears so much more. It may be paper thin, but it is thick with the stories of our generations.

Rabbi Ilana Berenbaum Grinblat

The Board of Rabbis of Southern California

This is the bread. … This is when you take a risk — when you decide to try that new job, new school, new business or project. This is when you’ve come to the edge, where you’ve planned and planned but know the moment has come to take the leap and venture into the unknown, hoping that the provisions you’ve taken with you will be enough.

Then add bitter herbs. … These are the losses, the heartbreaks. No one ever tries to add them to the recipe, but they inevitably get in. Some years their taste threatens to overpower all else. When they appear, be sure to smother them with:

Charoset. … This is the work. This is waking up at 5 a.m. feeling stressed, the weariness at the end of the day, the to-do list that never gets shorter, no matter how many tasks you accomplish.

But mixed in is the secret ingredient, the honey — the love — that gives meaning to all these sacrifices.

Be forewarned: This sandwich is extremely messy. The second you take a bite, it’ll go everywhere. The mess is unavoidable. Any efforts to prevent the mess will surely fail.

This combination of ingredients may seem odd, but by some miracle, if you make it right, the sandwich is delicious. Year after year, you can’t get enough. … And it all begins with the bread.

Rabbi Jason Weiner

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Knesset Israel

Most commentators notice the invitation aspect of this phrase and the importance of commencing our seder by welcoming guests. Indeed, there are many aspects to the seder meant to enhance the feeling of being free individuals — such as reclining, having a beautifully set table with our best finery and filling one another’s cups.

I believe there is another crucial message in this passage: Our rabbis, particularly those quoted in the haggadah, knew what it meant to be oppressed and downtrodden. They lived during a time of Roman persecution. Some were even killed for teaching Torah. They wanted their fellow Jews to feel exalted and free on this night, but also never to lose touch with the experience of slavery. The Torah tells us that just as we were strangers in the land of Egypt, we must always be able to identify with the difficult experience of being alienated and persecuted. As we begin our seder, therefore, the haggadah reminds us that you are about to engage in a ritual in which you focus on the experience of freedom, of acting like royalty. Enjoy it — you deserve it. But never lose touch with what it means to be poor, hungry and afflicted. We must do everything we can to help ease the burden of the suffering, and step one is identifying with their struggle. We thus begin our seder by holding up the bread of affliction and reminding all those present that we used to eat this stuff, and some people don’t even have this. Let’s help them.

David Sacks

Television writer who podcasts at Torahonitunes.com

This amazing invitation that begins the seder sounds incredibly generous. But if you actually think about it — it makes no sense. On a practical level, who is going to hear you outside your front door? As such, the whole thing seems like an empty practice.

Or is it? Maybe the person who needs an invitation the most is already at the table. And maybe that person is you. In other words, you might be sitting there, but are you really there?

This concept of “being present” has been part of Torah consciousness for thousands of years.

The first “Be here now” was said by God to Moshe at Mount Sinai. HaShem tells Moshe, go up to Mount Sinai and be there (Exodus 24:12). The Modjitzer Rebbe points out that the “be there” part seems redundant. Once Moshe ascends, he already is there! Not so. Being “there” requires your thoughts and your heart to be equally present. No small thing.

So back to our question: Has anyone ever shown up at your seder after you issued that initial invitation?

The answer is yes. And it happens every year. To all of us. Who comes? Eliyahu HaNavi. Elijah the Prophet. The one who announces the arrival of the Messiah. Because we show up. He shows up, too.

The whole world is waiting for the Jewish people to actually be “there.” And when that happens — and it is the destiny of the world that it will — everything changes.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.