Fifty-six years and 350 women after the first (non-Orthodox) female rabbi was ordained, the Orthodox Union took a stand last week.

The traditional community’s largest synagogue group retained one detail while reaffirming its opposition to ordaining women.

The board voted that four O.U. synagogues presently with women rabbis would be allowed to retain their membership in good standing.

The O.U.’s investigative update began more than a year ago. Seven rabbis were impaneled and handed two central questions to evaluate:

- Is it halachically (by Jewish law) acceptable for a synagogue to employ a woman in a clergy function?

- What is the broadest spectrum of professional roles within a synagogue that women can perform within the bounds of halacha?

On No. 1, they said no.

On No. 2, they said whatever duties women currently are performing are the limit.

However, the O. U. statement suggested its ruling was not necessarily final: “We envision a continuing process of dialogue and exploration.”

Across the Orthodox world, right and left, hardly anyone seemed pleased.

The reaction of Rabba Sara Hurwitz, the first Orthodox woman rabbi – ordained in 2009 by Rabbi Avi Weiss – was typical.

Instead of criticizing the O.U., she saluted the mission accomplished by her side.

“The ordination of women has unquestionably been a positive development for Orthodox Judaism,” Rabba Hurwitz said.

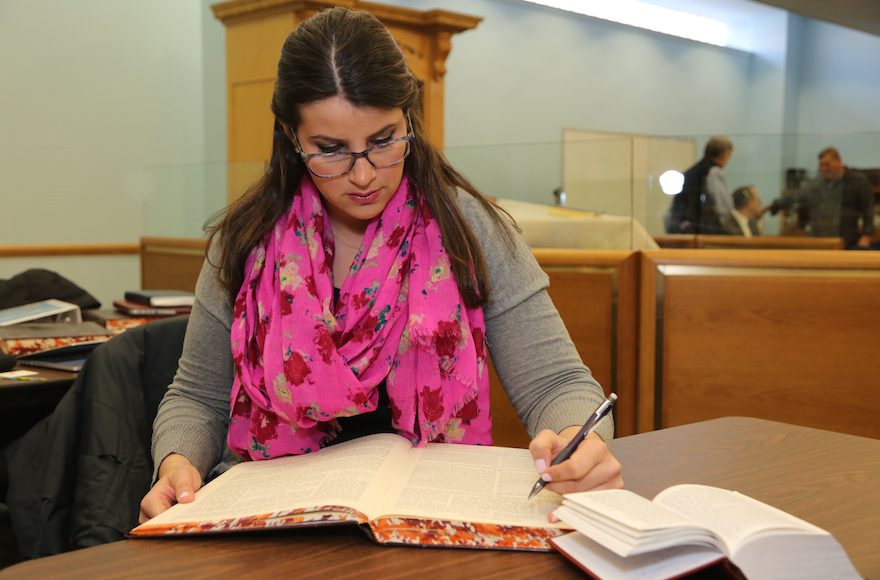

All four women rabbis at now officially sanctioned O.U. synagogues graduated from Yeshivat Maharat, a liberal Orthodox seminary that ordains women. Rabba Hurwitz is the dean. “The work our graduates are doing is within the scope of Jewish law,” she said. “We will continue to provide a pathway to women who want to share their Torah knowledge with their communities.”

Rabbi Weiss admitted mixed feelings about the O.U. statement.

“On the positive side,” he said, “the O.U.’s decision supports many of Yeshivat Maharat’s initiatives to further women’s learning and religious leadership. In the end, as Rabbi Norman Lamm has pointed out, the issue of women’s semikha is not halakhic but sociological.

“On the negative side, the decision, regrettably, is further indication that they are moving towards centralizing synagogue policies. One can only imagine what other centralizing policies are yet to be imposed.”

Instead of rabba, some Yeshivat Maharat graduates take the title rabbanit, as has Rabbanit Alissa Thomas-Newborn of B’nai David Judea in Pico-Robertson. “She has been a tremendous asset to our congregation,” said senior Rabbi Yosef Kanefsky.

Another prominent liberal Orthodox rabbi says that the Orthodox Union’s affirmation only confirms long-held convictions about leaders who lean to the right.

“The writings of the O.U. regarding women spiritual leaders saddens us,” said Open Orthodox Rabbi Shmuel Herzfeld of Ohev Shalom – The National Synagogue, Washington, D.C. “Once again we see them defining their faith as being about opposition to women.

“We believe in a faith that is so much more,” he said. “We believe in a faith that is inclusive and open. We don’t see gender of a person as relevant to that holy mission.”

On the right, Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein, who recently made aliyah after four decades in Los Angeles as an educator and writer, was not surprised by the stance. He congratulated the O.U. on its statement, calling it “wise, compassionate and balanced.”

He presented two further perspectives.

“Of course some are profoundly disappointed the O.U. took any position about female rabbis,” Rabbi Adlerstein said. “Others are disappointed that the O.U. didn’t put its foot down with a more resounding thump and boot out any shul that was not in compliance.”

Rabbi Adlerstein said the O.U.’s decision is based on wisdom that transcends the topic of women clergy.

“It asserts a traditional belief in mesorah (transmission of tradition) and the protocols of halachic decision-making in establishing the qualifications for who participates in the determination of halacha at the highest levels, in the need to temper autonomy with Torah authority and in the value of what the traditional community calls meta-halacha.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.