Originally published on December 18, 2008.

I originally planned to write a column about the flood of condemnations that Muslim leaders issued following the massacre in Mumbai, and how disappointed I was not to find a single fatwa in those texts, nor a mention of any religious offense: no “sin,” no “hell,” nor “apostasy.”

I was also tempted to write about liberated Western TV anchors finally shaking off those funny adjectives: “activists,” “militants” and “fighters” and returning to good old-fashioned “terrorists” — a glorious triumph of the English language over years of politically correct oppression.

But I had to suspend those plans and pay my dues first to the gods of history, which, for us Jews, must take precedence over all other gods.

This obligation is pounded into us by the first commandment: “I am the Lord your God who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery. Thou shall not have any other god before me.” In other words, to recognize me, says God, you must acknowledge your past, for I am revealing myself to you through the movements of history, or, put in modern vocabulary: If you forget your past, gone is your Jewish identity.

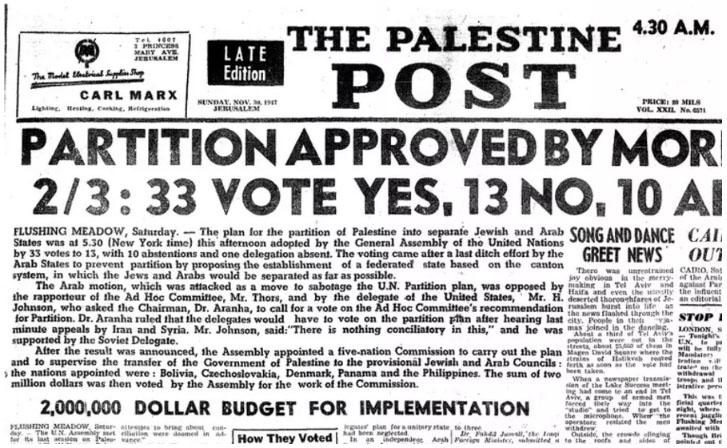

Why dwell on lost history? Because last month saw the anniversary of one of the most significant events in Jewish history, perhaps the most significant since the Exodus from Egypt — Nov. 29, 1947 — the day the U.N. General Assembly voted 33-13 to partition Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state.

Believe it or not, but this momentous event, which changed so dramatically the physical, spiritual and political life of every Jew in our generation, as well as the course of history in general, passed virtually unnoticed in our community, including in the pages of this paper.

I felt compelled therefore to amend this thankless rebuff of history and do what I can to compensate for the loss of opportunity. Imagine if the Jewish community in Los Angeles invited the consuls general of the 33 countries who voted yes on that fateful day to thank them publicly for listening to their conscience and, defying the pressures of the time (and there were millions of such pressures), voting to grant the Jewish nation what other nations take for granted — a state of its own. I can see 33 flags hanging from The Jewish Federation building, 33 bands representing their respective countries and the word “yes” repeated in 33 different languages in a staged reenactment of that miraculous and fateful vote in 1947.

Too theatrical? Extravagant?

Let’s face it. It’s not very often that we can honestly thank 33 countries for their governments’ decisions, especially not these days. And it’s not very often that we can forge a network of friendships with 33 local ethnic communities representing: Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Byelorussian SSR, Canada, Costa Rica, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, France, Guatemala, Haiti, Iceland, Liberia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Sweden, Ukrainian SSR, Union of South Africa, United States, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Uruguay and Venezuela.

I purposely spell out the names of these countries, in case anyone wonders whom they ought to thank for that spectacular turn that Jewish history took in November 1947 and for the dignity, pride and self-image world Jewry has enjoyed since.

Each of these names harbors an intriguing story behind its yes vote. Some voted yes out of moral conviction (e.g., Brazil, Guatemala), some through diplomatic arm-twisting (e.g., Philippines, Haiti) and others as a result of personal pleadings of ordinary, courageous Jews who understood the collective responsibility that history bestowed upon them in 1947.

A brief, yet fascinating account of some of these stories can be found in Benny Morris’ new book, “1948” (Yale University Press, 2008, pages 51-61). Others are still to be unearthed and are patiently awaiting a creative historian, novelist or filmmaker to be lifted from oblivion and added to the crown of Jewish lore and world history.

The story behind the pivotal U.S. vote is perhaps the best known and highlights the courage of Eddie Jacobson, President Harry S. Truman’s friend and former business partner from Kansas City, Mo., who risked that friendship and wrote to Truman on Oct. 3, 1947: “Harry, my people need help and I am appealing to you to help them.” To which Truman answered evasively: “When I see you I’ll tell you just what the difficulties are.”

Still, Jacobson did not give up; he did not mind being called “pushy Jew” and pleaded with Truman to grant one more audience to Chaim Weizmann, the engine behind the Zionist effort, who was not happy at all with the way the State Department was dragging its feet.

Weizmann had good reason to be nervous, for the outcome remained uncertain until literally minutes before the actual vote. In a preliminary vote taken on Nov. 25, six Latin American countries abstained, and the required two-thirds majority was not obtained. And while the fate of one whole nation was hanging in the balance, the Arabs were lobbying aggressively, promising money, oil and bloodshed. Yet, at the end of the day, the miracle did happen: 33 ayes, 13 nays and 10 abstains — a brand new chapter in world history.

The no and abstaining votes unfold heroic stories of their own. One of those tells us of a letter exchange between Albert Einstein and Jawaharlal Nehru, then the prime minister of India, which was discovered in Israeli archives (The Guardian, Feb. 16, 2005).

In his plea, which Nehru politely declined, Einstein wrote: “The Jewish people alone has for centuries been in the anomalous position of being victimized and hounded as a people, though bereft of all the rights and protections which even the smallest people normally has…. Zionism offered the means of ending this discrimination. Through the return to the land to which they were bound by close historic ties … Jews sought to abolish their pariah status among peoples.”

And concerning the Arabs’ demands to own all of Palestine, Einstein wrote: “In the august scale of justice, which weighs need against need, there is no doubt as to whose [need] is more heavy.”

I find Einstein’s letter heroic, not because of any risk he took in this exchange, but because he agreed to forgo personal hesitations and harness his worldwide reputation and friendly relations with Nehru to his people’s calling. Einstein was a lukewarm Zionist, constantly torn between his belief that Zionism is the only just solution and his deep concern about potential misuse of power by the ensuing Jewish state.

On one occasion, in 1938, he even expressed preference for a binational one-state solution. He could have easily told his “mobilizers” from the Jewish Agency Executive: “Sorry, I am not your guy”; “I can’t get involved in politics right now”; “I don’t know Nehru well enough,” or “I myself am often critical of the course the Zionist movement has taken.” (Sound familiar?) Yet, when he heard the bells of history ringing his name, he knew exactly what was to be done; he put aside those personal hesitations and stood firmly with his people.

We owe it to the gods of history to mention Einstein and Jacobson and 32 other heroic stories that heralded the greatest gift history has given us: A state that contributes to humanity more than all the countries in the United Nations that mourn its birth (paraphrasing Daniel Gillerman). We owe it because the offerings we give to the gods of history today will strengthen the spines of our children and grandchildren tomorrow.

Indeed, in campuses ruled by Noam Chomsky’s disciples and “New Maranos” (Jewish faculty peer-pressured into silence), where will Jewish students find the courage to stand up to anti-Israel slurs in the cafeteria, library or the classroom, if they have not heard about Nov. 29, Eddie Jacobson or any of the other 32 heroic stories that led to the U.N. vote of 1947? Where would they gather the courage to lift their eyes from the salad plate and tell their abuser: “Accuse me; I am Albert Einstein’s kin, and what you just said offends everything I cherish and stand for. If you value our friendship, read first about Nov. 29, 1947.”

Speaking of college campuses, imagine Hillel students at UCLA or UC Irvine inviting student organizations representing all the 33 yes-voting countries to a “thanksgiving get-together” on Nov. 29. This could include a multicultural talent show, a reenactment of the U.N. vote or a reading of U.N. Resolution 181. Imagine what it would do to Israel’s image and Jewish posture on campus.

It is for this reason that I decided to devote this

column to the gift of history: The miracle of Nov. 29, 1947.

Finally, to compensate for overlooking the November miracle

in 2008, I am including a poem that Natan Alterman

wrote on Dec. 19, 1947, soon after the UN decision to

partition Palestine, which reflects his understanding of the

sacrifices that everyone knew would have to be made

for independence. It is Alterman’s most popular poem

and is often read in school assemblies and at public gatherings

in Israel.

The Silver Platter

By Natan Alterman

Translated from the Hebrew by David P. Stern

“No state is served to a nation on a silver platter.”

(Chaim Weizmann, December 15, 1947)

…And the land will grow still

Crimson skies dimming, misting

Slowly paling again

Over smoking frontiers

As the nation stands up

Torn at heart but existing

To receive its first wonder

In two thousand years

As the moment draws near

It will rise, darkness facing

Stand straight in the moonlight

In terror and joy

…When across from it step out

Towards it slowly pacing

In plain sight of all

A young girl and a boy

Dressed in battle gear, dirty

Shoes heavy with grime

On the path they will climb up

While their lips remain sealed

To change garb, to wipe brow

They have not yet found time

Still bone weary from days

And from nights in the field

Full of endless fatigue

And all drained of emotion

Yet the dew of their youth

Is still seen on their head

Thus like statues they stand

Stiff and still with no motion

And no sign that will show

If they live or are dead

Then a nation in tears

And amazed at this matter

Will ask: who are you?

And the two will then say

With soft voice: We–

Are the silver platter

On which the Jews’ state

Was presented today

Then they fall back in darkness

As the dazed nation looks

And the rest can be found

In the history books.

Judea Pearl is a UCLA professor and president of the Daniel Pearl Foundation (www.danielpearl.org), named after his son. He and his wife, Ruth, are editors of “I Am Jewish: Personal Reflections Inspired by the Last Words of Daniel Pearl” (Jewish Light, 2004), winner of the National Jewish Book Award.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.