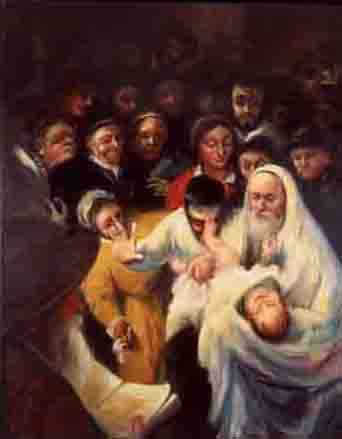

Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons. When our oldest daughter was pregnant and learned she was having a boy, there was never any doubt that we would all be celebrating a ritual circumcision after his birth. Even before he was born, we decided to co-sponsor the big event with his other grandparents because we all live in the same town.In recent years, controversy concerning circumcision has surfaced across the globe. In 2011, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill prohibiting California cities from banning the practice. As recently as this past spring, efforts to prevent circumcision were publicized in Iceland. These efforts always raise concerns for Jews and others about interference with religious freedom, and with good reason.

In the Jewish tradition, the rite of circumcision, known as a brit milah in Hebrew or more colloquially as a bris, marks a male’s entry into the covenant established between God and the Jewish people. The Torah states that God commanded Abraham to circumcise every male at the age of eight days.

Although the origins of this ceremony derive from the Torah, throughout the centuries the brit has represented a staple of Jewish culture. Its staying power even among nonreligious Jews is truly remarkable. The brit is similar to most other Jewish life cycle events in that it reflects a blend of rabbinic tradition and the cultural practices of the people. So although it is an enduring sign of the covenant, it also reflects the culture of the Jewish people across space and time.

Very little about the actual content of the brit as practiced today is found either in the Torah or the Talmud. The rabbis in late antiquity prescribed the particular prayers and blessings for a brit, but many of the actual customs were cultural innovations of the Jewish people. These customs also were heavily influenced by the cultures of the surrounding non-Jewish communities in which the Jews lived for centuries.

Many familiar aspects of the brit were drawn from the Christian baptism ceremony, a reality not all that surprising given that baptism replaced circumcision in early Christianity. The evening before circumcision was generally believed to be the most dangerous time for the baby and his mother, and so at one time Jewish communities held all-night vigils to protect the infants from evil spirits. There is much evidence to suggest that these vigils revealed a marked similarity to Christian customs that arose in connection with the evening preceding a baptism. Jews and Christians believed that the presence of food could mollify evil spirits and so the practice developed of a festive meal on the evening before the brit.

Throughout the centuries the brit has represented a staple of Jewish culture. Its staying power even among nonreligious Jews is truly remarkable.

The prophet Elijah also earned a prominent place in the brit. On the one hand, his role was derived from rabbinic interpretations of a biblical verse about Elijah that the rabbis believed referred to circumcision. Still, according to Jewish folklore, Elijah was the guardian angel of children and believed to have supernatural powers as a miracle worker. Even today, every brit has a special chair that is reserved for Elijah.

The history of the brit demonstrates that the staying power of Jewish tradition generally derives from its ability to forge Jewish law and Jewish culture, as well as adapt practices from the outside cultures in which Jews have lived for centuries. This history of unique Jewish content and selective adaptation from the host cultures is what has kept Jewish tradition alive and relevant for more than 2,000 years.

Vigils on the evening before the brit are no longer common, but we sat for hours after the ceremony with family and friends, munching on bagels and lox, enjoying our grandson, and feeling a deep sense of gratitude. The feel of the brit was very similar to the wedding of our children more than five years ago. Even the two rabbis who officiated at the wedding joined in our festivities — one Conservative and one Reform.

How blessed are we to be part of a tradition thousands of years old that furnishes ready-made opportunities to celebrate life’s milestones in a way that has evolved somewhat over time but still retains its uniquely Jewish character.

Roberta Rosenthal Kwall is the Raymond P. Niro Professor at DePaul University College of Law. She is the author of “The Myth of the Cultural Jew: Culture and Law in Jewish Tradition” (Oxford University Press, 2015) and is currently working on a book about

transmitting Jewish tradition in a diverse world.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.