Photo from Pixabay

Photo from Pixabay One Shabbat morning, to help explain the Torah portion, I taught my congregation how to fold a simple origami model.

Let me explain.

Parashat B’shalach, which we read this week, recounts the most miraculous moment in the history of our people: the parting of the Red Sea. What’s remarkable is how we responded, both at that moment and throughout our history.

The passage after the crossing begins Az yashir Moshe, “Then Moses sang.” This is the first record of anyone singing in the Torah. In fact, the passage is so associated with music that it’s universally known as Shirat Hayam, Song of the Sea.

After the song, we are told that Miriam took up her timbrel and danced. This is the first record of anyone dancing in the Torah.

This playful spirit even inspired the scribes who wrote our Torah scrolls. In every Torah (or Bible or prayer book) the words of this passage are arranged in an unusual way: The text is broken up with two wide spaces per line, alternating with three wide spaces per line.

Some observers say it’s an ancient pictogram, conveying its meaning through its resemblance to a physical object. What object? A brick wall, symbolizing God’s holding back the waters as the Israelites passed through on dry land: “the waters forming a wall for them on their right and on their left.” (Exodus 14:29)

There’s another interesting dimension to this passage. When it’s chanted in Ashkenazi synagogues, we use a special melody for some of the verses. These verses are chanted antiphonally — that is, alternating between the reader and the congregation.

Imagine for a moment how the scribe who came up with this pictogram felt. “I could write these words in paragraph form, but instead I’m going to arrange them like bricks in a wall!” What about the person who first devised the unique tune for chanting the passage? “I’m going to use a different melody, and involve the congregation in the chanting!”

Thousands of years after the experience of that remarkable event, an inspired scribe responded to it with a wonderful pictogram. And a Torah chanter interpreted the song by composing a singular melody and an innovative way of involving the congregation.

Like Moses and Miriam, the scribe and the chanter responded in spontaneous and heartfelt ways. But now these innovative practices have become routine. Our scribes utilize this same pattern in every scroll, and publishers re-create it in every Bible and prayer book. Our Torah readers chant the same melody for this passage year after year: millions of recitations over hundreds of years, in the same melody.

If we perform actions only in the prescribed way, we are missing out.

Don’t get me wrong. Traditions can be wonderful. There’s great satisfaction in knowing that you have performed a ritual in the prescribed manner. There’s also great value in heritage, in absorbing and passing along received wisdom.

But if we perform the actions only in the prescribed way, we’re missing out. Like the ancient scribe and Torah chanter, each of us needs to find our own way to connect to the sacred, to respond creatively to the defining events of our history. When we do, something miraculous happens inside us, enabling us to experience the sacred as our ancestors did.

Here’s where the origami comes in.

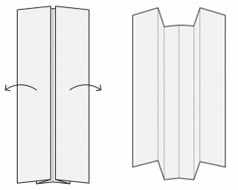

As an origami artist, I was inspired to create a simple model of the Red Sea parting. After teaching my congregation to fold the model, I invited members to hold it close to their eyes, gaze through the passageway and imagine that they themselves were present at that sacred event, proceeding forward between walls of water.

How did they walk? What did they hear? What did they see? What could they smell? What were their thoughts and fears? Did they feel the presence of the Divine?

In that moment, the people in my shul experienced a kind of transformation. They were able to connect to our sacred history. Just as Moses and Miriam did, just the Torah scribe and the Torah chanter did.

While tradition has the power to connect us to countless generations past, our personal response to the sacred through the creative arts has the power to engage and transform us individually. Both are essential for a full spiritual life.

Joel Stern is the author of “Jewish Holiday Origami” and many other papercraft books.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.