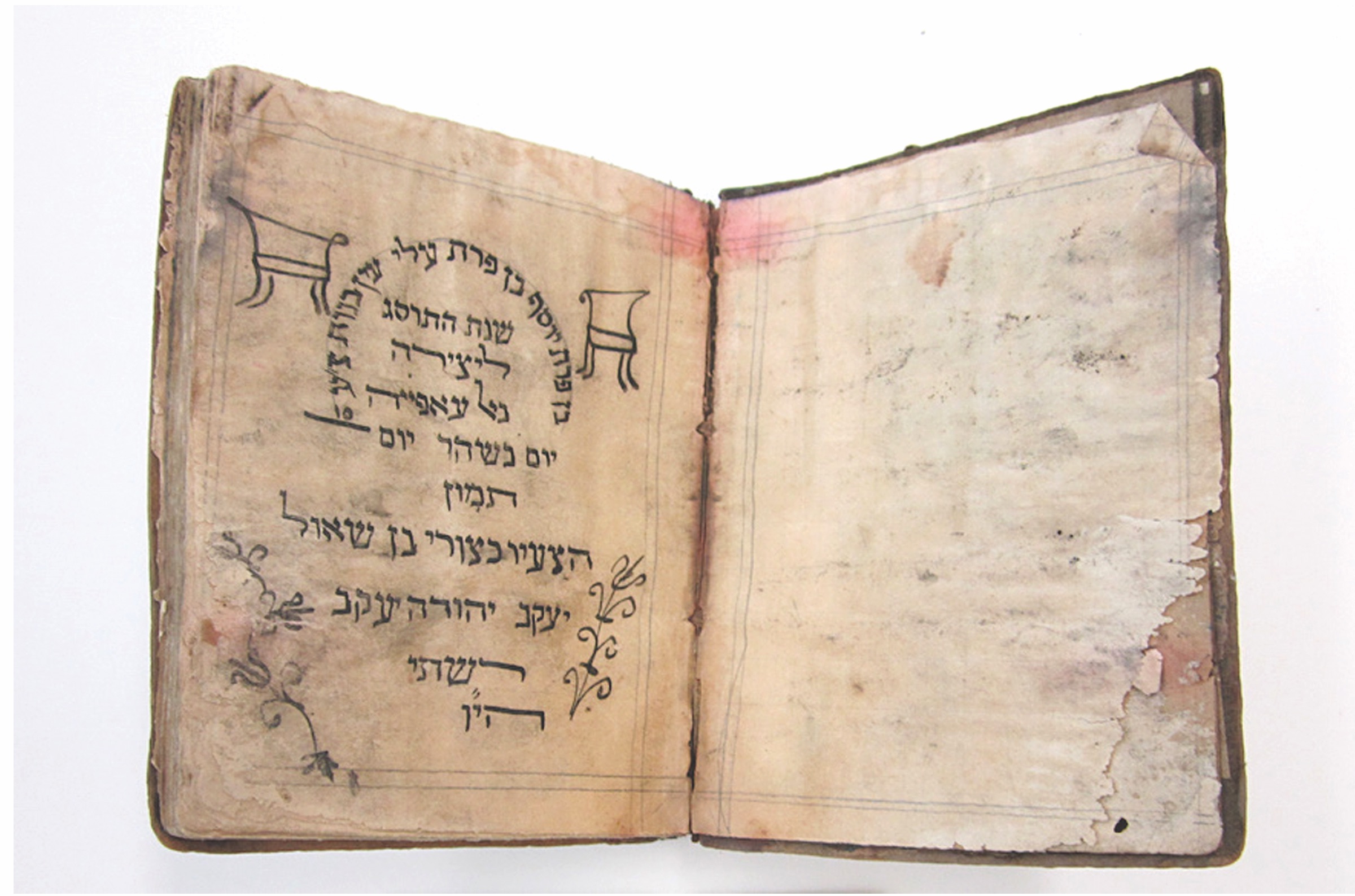

This Passover haggadah from 1902, one of very few Hebrew manuscripts recovered from Saddam Hussein’s intelligence headquarters, was hand-lettered and decorated by an Iraqi youth. Photo from National Archives

This Passover haggadah from 1902, one of very few Hebrew manuscripts recovered from Saddam Hussein’s intelligence headquarters, was hand-lettered and decorated by an Iraqi youth. Photo from National Archives Eighty-six-year-old Joseph Samuels fled his native Iraq in 1948 and has called Santa Monica home for over 30 years. When a traveling exhibition featuring pieces from the Iraqi Jewish Archive (IJA) — a collection of more than 2,700 Iraqi-Jewish artifacts — had a six-week stay at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library in Yorba Linda two years ago, he knew he had to go.

“I had tears in my eyes,” said Samuels, who lived through violent pogroms in Iraq. “Seeing the artifacts brought back memories of my life in Baghdad, like how we celebrated the Jewish festivals and going to synagogue with my father. It made the history come to life.”

Samuels hopes future generations of Mizrahi Jews get a glimpse into that forgotten history — rediscovered by U.S. forces during the invasion of Iraq 2003 — by seeing the artifacts, some of which date as far back as the 16th century, including Torah scrolls, prayer books and community records.

But that dream could be in danger.

After several extensions on a return date, the U.S. State Department is scheduled to return the IJA to the Iraqi government in September 2018.

Samuels, along with other Mizrahi Jews, Jewish organizations and politicians, vehemently opposes returning the artifacts to Iraq, whose Jewish community today is practically nonexistent.

“This is the property of the Jews of Iraq,” Samuels said. “If it goes back to Iraq, no Jews will be able to go there to visit their history. I feel very strongly about it. It will sadden me a lot if the archive is returned.”

More than 850,000 Jews were displaced from Arab countries and Iran during the 20th century, transforming thriving communities into hordes of refugees. Much of the refugee crisis was generated by pogroms in the Middle East and North Africa after Israel’s victory in the 1948 War of Independence against Arab armies. Today, there are fewer than 3,000 Jews living in Arab countries. Most Mizrahi Jews, those who descend from the Middle East and North Africa, are dispersed across Israel, Europe and North America, with a sizable population in Los Angeles.

The IJA artifacts either were left behind by exiled Iraqi Jews who had flourished there for more than 2,000 years or were confiscated when Jews were forced to flee and were stripped of assets and citizenship.

According to Samuels, a member of Kahal Joseph Congregation, a Sephardic Temple in Westwood, Los Angeles’ sizable Mizrahi community overwhelmingly opposes returning any artifacts to Iraq. Nationally, Jewish Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.) wrote a letter to Secretary of State Rex Tillerson in October asking him to work with Jewish groups to find a suitable home for the IJA.

Gina Waldman, co-founder of Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa (JIMENA), a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving Mizrahi culture and history, is a Libyan-born Jew who fled her birthplace of Tripoli in 1967. She likened the IJA situation to giving Jewish-owned artwork confiscated by Nazis during the Holocaust back to Germany.

“The Iraqi government claims these artifacts represent Iraqi national heritage. No, it’s Jewish heritage.” — Gina Waldman

“When the art was stolen from Jewish gallery owners or private Jewish owners by the Nazis, we tried to get it back,” she said. “If it showed up in the United States, we wouldn’t return it back to Germany, so why would this be so different? The Iraqi government claims these artifacts represent Iraqi national heritage. No, it’s Jewish heritage.”

David Myers, president and CEO of the Center for Jewish History in New York and UCLA’s Sady and Ludwig Kahn Chair in Jewish History, also expressed concern about the IJA’s potential return to Iraq but declined to wade too deep into what he called a “sensitive diplomatic issue.”

The treasure trove of Iraqi-Jewish artifacts was unearthed in May 2003 during the Iraq War when a U.S. Army unit stormed the headquarters of the Mukhabarat, Saddam Hussein’s intelligence services. The unit didn’t find the weapons of mass destruction it was looking for, but it did find waterlogged and moldy Iraqi-Jewish artifacts in a basement damaged by flooding after a bombing campaign.

The U.S. government reached an agreement with a provisional Iraqi government to refurbish the collection under the auspices of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. More than $3 million was spent on preserving, cataloging, digitizing and ultimately creating an exhibition. Part of the deal included an eventual return of the archives to Iraq.

However, recent comments made by the U.S. State Department appear to be leaving the door open to revisit the IJA situation with the Iraqis.

“Maintaining the archive outside of Iraq is possible but would require a new agreement between the government of Iraq and a temporary host institution or government,” State Department spokesman Pablo Rodriguez told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in October.

Los Angeles County Deputy District Attorney Elan Carr, who lives in the Pico-Robertson area, was born to an Iraqi-Jewish family that escaped to the United States during the pre-Saddam era. He told the Journal he’d like to see an appointed American negotiator work closely with the Iraqis.

“There’s no shortage of names,” he said. “We have all kinds of ambassadors on issues involving world Jewry, anti-Semitism and many world Jewish issues who are familiar with this.”

Few are as familiar as Carr, who was in Iraq as an Army reservist when the IJA artifacts were discovered in 2003. During his time there, Carr and state department officials were shown storage rooms in Baghdad museums by curators where thousands of additional Iraqi-Jewish artifacts, including more than 400 Torah scrolls stripped of gem-adorned coverings and precious metals, still remain.

“I couldn’t believe what I was seeing,” Carr said.

If you ask Carr, the IJA should be the tip of the iceberg in any negotiations with the Iraqis concerning Jewish artifacts.

“I think the negotiations shouldn’t be just about this particular trove, as important as it is,” he said. “Even if we were successful with keeping the archives here, that comes at what cost? This is one of many troves. There has to be in, my view, a comprehensive global negotiation about what to do with Jewish artifacts in Iraq, and Jewish places there, too, like shrines, sites and cemeteries.”

When asked if he can imagine the Iraqi government preserving the IJA and other artifacts and remnants of Iraqi Jewry, Carr expressed shades of optimism.

“Yes, I can imagine it. I don’t think it would be easy and I don’t they’d do it enthusiastically, but it depends on the negotiation and how badly they’d like to please the United States and how important the issue becomes to the United States,” he said. “I’ll tell you this: They haven’t destroyed them yet. They could’ve but they haven’t.”

The IJA currently is on display at the Jewish Museum of Maryland in Baltimore, where it is scheduled to remain through Jan. 15.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.