On a bright, clear December morning, about a dozen individuals, most of them Persian Jews, gathered on plush sofas in the wood-paneled den of a large home in north Beverly Hills, hoping to start a movement.

Arya Marvazy, one of the gathering’s organizers, sat on a high stool facing the semicircle of attentive faces and introduced the event, a monthly meeting of the inaugural cohort of the JQ Persian Pride Fellowship, “a nine-month leadership, activism and training program for Iranian LGBTQ individuals and allies,” he said.

About two years after Marvazy came out as a gay man in a Facebook video that quickly went viral in his Persian-Jewish community, the 31-year-old is leading a cohort of 12 fellows, including himself and fellow organizer Amanda Maddahi. The group, whose members range in age from 20s to early 40s, includes Muslims and Jews, as well as two fellows who identify as allies rather than LGBTQ.

Marvazy said in an interview that the fellowship’s aims lie in “moving our community forward and getting the good message of queer equality out to the Persian masses,” thereby opening a conversation that the largely conservative community often prefers to leave closed.

The main components of the fellowship, according to Marvazy, an assistant director for the West Hollywood-based Jewish LGBTQ organization JQ International, include leadership and activism training sessions, panel discussions such as the Dec. 17 parlor meeting and, eventually, programs organized by fellows.

While guests picked at a bagel breakfast set out on a bar in the back of the room, Marvazy introduced the morning’s speakers: Joseph Harounian, an openly gay Persian man and founder of a West Los Angeles wellness center; Mastaneh Moghadam, a social worker who has worked with the Iranian LGBTQ community for more than a decade; and Vennus Zand, an Orange County-based therapist who discussed a qualitative study of the coming-out process for gay Persian men that she conducted after her brother came out to her.

Moghadam started the discussion, recounting the atmosphere when she first started to talk to people about LGBTQ issues in the local Persian community 15 years ago. “It was so dark and not talked about, and ‘nobody can know about it,’ ” she said. “It was such a closed conversation.”

She described how she struggled to book family members of gay and lesbian Persian youth to speak on KIRN, a local Persian-language radio station. “Everybody’s feedback to me was ‘Mastaneh, nobody will come. Mastaneh, the community isn’t ready.’ ”

Nonetheless, she persisted, and the feedback was encouraging.

“One mother who appeared on the KIRN show said to me, ‘This was so therapeutic. I wish we could do this every week.’ And I said, ‘We can,’ ” Moghadam said.

“The idea that I can perhaps inspire someone else to see that it’s OK to be yourself and to be open makes me want

to keep going.” — Matthew Nouriel

That conversation was the seed of a long-running support group for Persian people struggling to understand a family member’s LGBTQ identity. Often, when members were reticent to return to the group, Moghadam said she reminded them, “This is more than a support group. This is a movement.”

Harounian spoke about his coming-out experience when he was in his early 30s. For years he struggled while hiding his identity from his family, frequently making excuses for why he wouldn’t date the women they set him up with. Finally, in 2000, he couldn’t do it any longer.

“I woke up one day and said, ‘Enough is enough,’” he said. “‘Life is too short. I need to start living.’”

Others in the room shared similar stories of struggling with their families’ lack of knowledge and acceptance.

Shirin Golshani, a 30-year-old occupational therapist, joined the fellowship after watching her friend, organizer Maddahi, struggle to obtain the acceptance of her family and community after coming out.

“I felt so bad that there was nothing I could do but just be there for her,” Golshani said in an interview. “And I think that this fellowship is such an amazing way of getting educated.”

Growing up in the Beverly Hills Persian community, Golshani maintained a neutral attitude on LGBTQ topics but heard people close to her express opinions ranging from indifference to distaste. While her parents remain positive about her decision to join the fellowship as an ally, she said she senses their wariness.

“I think they’re even still trying to warm up to the idea that their Persian Jewish daughter is so closely tied to this community,” she said. “And I know that in a sense they’re wondering, ‘Are people going to think she identifies as LGBTQ?’ Even though I don’t.”

Marvazy said he hopes the fellowship, which began in November, will be the template for many more cohorts to come. He said in March, which JQ International has declared its third annual Persian Pride Month, fellows will be responsible for organizing their own projects in the community.

For some, the fellowship reinforces their informal roles as mentors for younger people with similar difficulties.

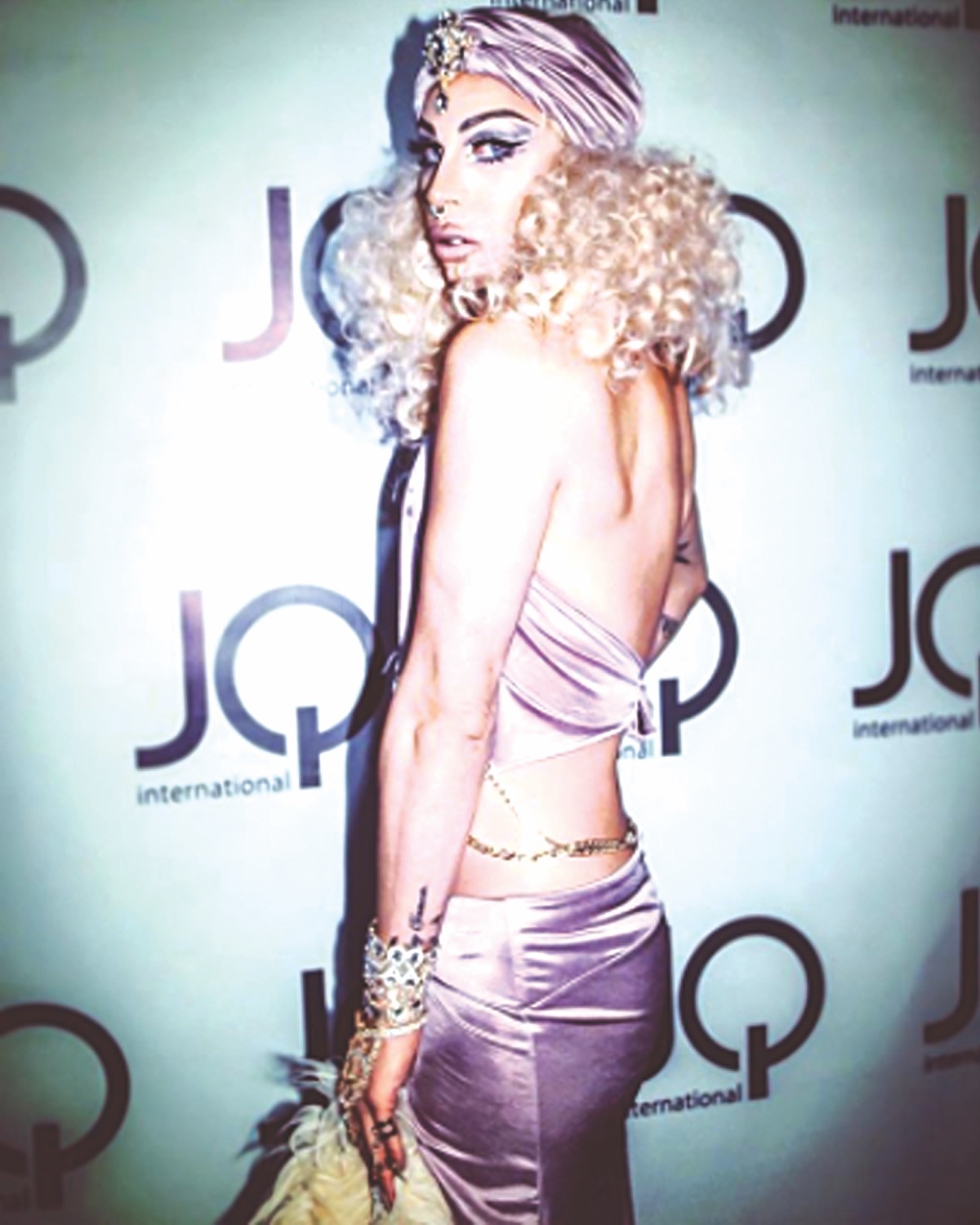

Matthew Nouriel, who came out as gay at 15 after moving to L.A. from London and now performs as a drag queen, said he sometimes receives messages online from other LGBTQ Persian people seeking advice and encouragement.

Recently, for instance, he began counseling an 18-year-old gay man in Iran who found Nouriel on Instragram, sharing tips on how to navigate coming out or staying closeted, as well as offering makeup pointers. Nouriel said he encouraged the young man to put his safety first when deciding whether to come out. He believes his mentee benefits from their talks.

“The more I put myself out there, the more I feel like those walls are being broken down, even if only a little,” Nouriel wrote in an email to the Journal. “The idea that I can perhaps inspire someone else to see that it’s OK to be yourself and to be open makes me want to keep going.”

In a way, the fellowship reverses the isolation he felt growing up gay and Persian, he wrote.

“I felt the need to retract myself from the community when I was growing up. Having this fellowship has introduced me to a whole group of people I otherwise may have never met,” he wrote, adding, “Strength in numbers!”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.