Reuters/David W Cerny

Reuters/David W Cerny “Relevance, relevance you shall pursue.”

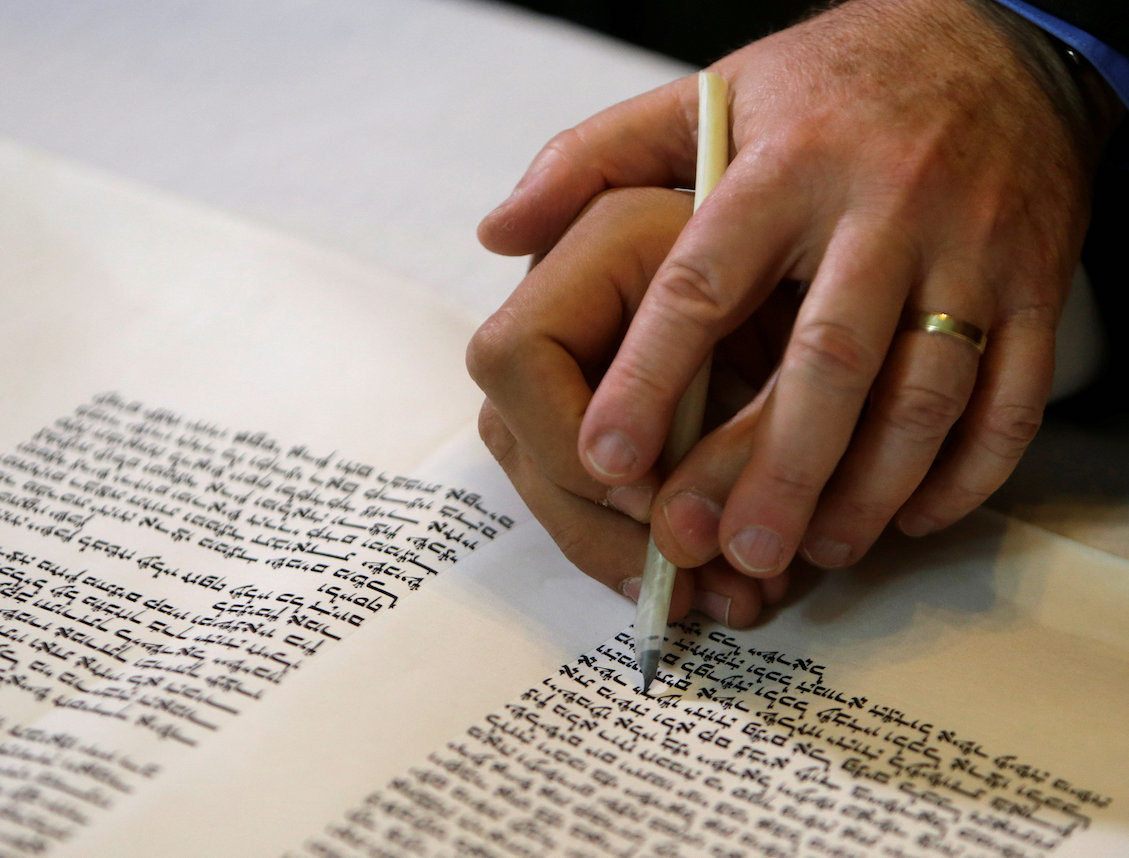

This is the torah, or teaching, of the commentator, charged by his or her editor to make sense of our ancient tradition and — crucially — to bring it home.

Sometimes, however, Torah does the work for us, and brings its message right to our doorstep, as it does in this week’s parsha, Shoftim.

“You shall establish judges and executive authority throughout the cities that God gives to your tribes, so that they might adjudicate among the people with a standard of justice. … Justice, and justice again, shall you pursue, in order to live and inherit the land that God gives you” (Deuteronomy 16:18-20).

To all appearances, these verses destabilize a commonplace of the Jewish tradition, and they awaken our conscience in the process. Specifically, we axiomatically and routinely claim our land on the simple grounds that God gave it to us, the implication being that we have an inalienable right to inhabit and inherit it.

Parashat Shoftim, however, disabuses us of that misconception. In fact, the Covenant is a precondition for our inheritance, but it is not sufficient to realize it. Just because God gave us the land doesn’t mean that we get to take it. We must earn our inheritance by establishing a system of justice and, no less so, by dedicating ourselves to an ethic, a culture, of pursuing it at all costs. If we pervert justice, we violate the Covenant, and we negate our own claim.

But justice and its pursuit defy easy categorization and implicate people in various positions. Three of our most revered commentators, Rashi (1040-1105), Ibn Ezra (1089-1167) and Nachmanides (1194-1270), all read these verses similarly, and help us understand what is expected of whom.

The first criterion for the fulfillment of our obligation lies with the government or leadership. God commands Moses to “establish judges and executive authority,” meaning it is Moses and his delegates who must found a government, corresponding to our notions of the executive and the judiciary. (God alone legislates.)

The second criterion, “Justice, and justice again, shall you pursue,” depends on us. “We, the People” need to pursue justice doggedly, and we must accept judicial decisions even when they don’t favor us. In this way, Parashat Shoftim describes a partnership between the government and the citizenry, for the sake of a just society that merits its place.

So much for the roles we play, but what does justice actually look like? There are, to be sure, too many possible cases to name, but our parsha lays out one very telling, if extreme, example. If someone slays another person “unintentionally and without prior, known malice” (Deuteronomy 19:4), the killer can escape to a city of refuge, where fellow citizens cannot claim his life in retribution. As long as the killer acted “without prior, known malice,” he will find sanctuary.

By contrast, “if there is one filled with malice against another, who ambushes his fellow and sets out and fatally strikes him,” then the elders of the city must allow retribution by turning the criminal over to those who seek it (Deuteronomy 19:11-12). There is no refuge for the sinister and hate-filled.

The concept of the city of refuge allows the executive authority (the town elders) and the citizenry (those seeking retribution) to negotiate justice. Accidental death means that the elders cannot “extradite” the accidental killer to those who would have his head. Instead, the government must enforce a kind of grudging reconciliation for the sake of peace. However, if the killer acted maliciously, the elders must deny him refuge and turn him over to those who would kill him on account of the murder he committed.

Justice here hinges on the state of mind of the killer. Sin’ah, meaning hatred or malice, defines the crime and its consequences, which in turn represents the principle of a just society altogether, upon which fulfillment of the Covenant depends.

Today, no one condones blood feuds, despite the fact that Torah at least partially legitimates them. We can, however, derive an enduring principle from this otherwise outdated example: Hatred matters, and killing under its sway irretrievably violates justice. Anyone who acts accordingly necessarily relinquishes his own claims.

As neo-Nazis and their sympathizers marched through Charlottesville, Va., recently, they chanted the Nazi phrase “Blood and Soil,” presumably expressing a tribal claim to this land. History and common sense reduce their chant to sheer absurdity and nothing more.

But it is worth pointing out, additionally, that many of them make claims based on their sense of religion, and they fancy themselves heirs to a biblical tradition of sorts. It’s not just whiteness that they’re championing, but also a version of Christianity that purports to draw from Scripture. If so, the Bible spurns them and their pernicious claims, for they have spilled blood in hatred and blasphemed in so doing.

JOSHUA HOLO is dean of the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, Jack H. Skirball Campus in Los Angeles.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.