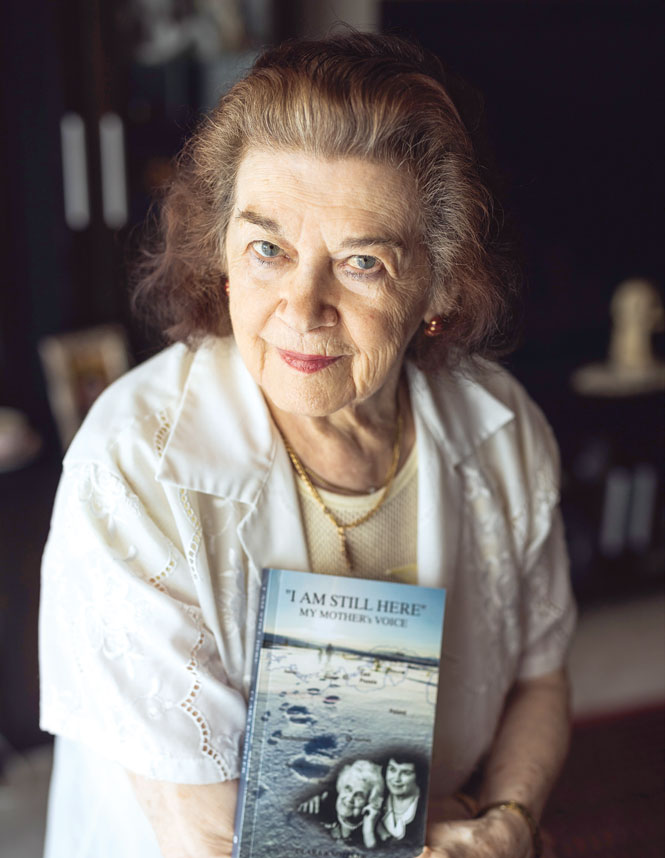

Clara Knopfler wrote a book about her and her mother’s Holocaust saga. Photo by David Miller

Clara Knopfler wrote a book about her and her mother’s Holocaust saga. Photo by David Miller Klara Deutsch was among the first survivors, along with her mother, Pepi, to return to her hometown of Cehul Silvaniei, Romania, in late April 1945.

She was 18, pale with shorn hair and clad in a hand-me-down dress. Her joints ached from 11 months of sleeping on the ground and other hard surfaces, and she was worried about the fate of her father and brother, and the bleak future she and her mother faced.

In their house, which had been looted, only the piano, a heavy, carved dining set and two beds remained. “It was all emptiness,” said Clara, who changed the spelling of her first name when she reached the United States.

Immediately, a Christian friend welcomed them back with baskets of apples and grapes, and a neighbor showed up with quilts and pillows. The next morning, Clara’s girlfriend Ildiko came by, with Clara’s navy velvet “sweet 16” dress, which she had rescued, draped over her arm. A day later Joseph, the son of a former employee, knocked on the door, teary-eyed, carrying Clara’s treasured accordion.

“These are the things that really make you think that there is the possibility to live in peace,” Clara said, 50 years later in an interview with what is now the USC Shoah Foundation “And if we don’t forget what happened to us, we may teach the world that it’s possible.”

Now Clara Knopfler, teaching people to co-exist has been her mission since 1976, when she began telling her story to history students at Eastchester High School in Eastchester, N.Y., where she taught French and Latin. Today, at 90, she speaks to history classes at California Lutheran University, Moorpark College and various high schools.

Clara was born on Jan. 19, 1927, to Pepi and Joseph Deutsch in Cehul Silvaniei, a Romanian city in Northern Transylvania. She had one brother, Zoltan, three years older.

Joseph owned a shoe store, selling commercially manufactured shoes as well as boots he fabricated in his shop, which occupied the front area of their comfortable two-bedroom house.

After Hitler ceded Northern Transylvania to Hungary in late August 1940, and Jews were restricted from attending public school, Joseph sent Clara to a new Jewish high school in Kolozsvar (formerly Cluj, Romania), 75 miles south.

But the school closed in March 1944, when Germany invaded Hungary, and Clara returned home.

Restrictions were imposed on Cehul Silvaniei’s Jews, and rumors circulated they would be shipped out to work.

On May 3, 1944, Clara’s family, along with Cehul Silvaniei’s 550 Jews, were transported to the Simleu Silvaniei ghetto, the former Klein brick factory, 32 miles south. They joined more than 8,000 people crowded together in muddy, unsanitary conditions.

A few weeks later, they were dispatched to Auschwitz. The men were ordered off the train first, and Clara watched as her father glanced back at her and Pepi, giving a slight wave.

The women then lined up while Dr. Josef Mengele directed them to one side or another. Pepi, a young-looking 45, was sent with Clara. “Why am I with you?” she asked her daughter, noticing all the mothers in the other group. Without answering, Clara pulled her mother closer to her.

The women were marched to Birkenau, where they were processed — “I think we will live like animals now,” Clara told Pepi — and taken to a barracks. After eight days, they were shipped to Kaiserwald, a concentration camp in Riga, Latvia.

There, they worked in a factory recycling batteries from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. daily. When darkness fell, around 10 p.m., the women began dozing off, causing the older German soldier who supervised them to strike them.

About a week later, the soldier approached Clara. “Little girl, do you sing German?” he asked. Clara started to cry, remembering the songs her father had taught her. She began singing, “Yours Is My Heart Alone,” by composer Franz Lehár, and the women hummed along, staying awake. This became a nightly ritual.

“[The German] had a heart, definitely,” Clara said, noting that he had found a nonviolent way to keep them working.

In early September, the women were taken to Stutthof concentration camp in East Prussia for three days, then to Dorbeck, a labor camp. They slept in tents and worked from sunup to sundown, digging anti-tank trenches.

Later in September, they were marched to Guttau, another labor camp in East Prussia, where they again dug trenches.

One day in early November, Pepi, who was ill, stood atop a trench Clara was digging. The Hitler Youth member who was supervising them suddenly began hitting her. “You old bag,” he shouted. “Work faster.”

Clara jumped out of the trench. “Stop,” she said. “She works for your Fuhrer 12 hours a day with the terrible food you give her.” Clara told him Pepi was her mother. “Don’t you have a mother?” she asked. “I do, but she’s German,” he answered, abruptly leaving.

The teenager returned the next day, handing Clara a carrot. “Eat this. It has some vitamins,” he said. He also gave her half a cigarette, telling her it would curb her hunger.

“This gave me hope forever afterward,” Clara recalled. “People can be changed.”

On the morning of Jan. 19, 1945, Clara’s 18th birthday, Pepi gave her a “layer cake,” three pieces of bread spread with margarine. A few hours later, the women were dispatched on a forced march, dragging themselves on frozen snow in the bitter cold.

On the second night, Clara heard the guards discussing their fate, whether to shoot or burn them. An older German soldier, whom the girls called Old Papa, spoke up. “Why worry about them? Let’s save our lives.” When the women awoke the next morning, the Germans were gone.

A few days later, Clara, Pepi and five others set out for home, finally reaching Cehul Silvaniei in late April.

Months later, Clara and Pepi learned that Zoltan had been shot in the head on his first day at Auschwitz for refusing to chop rocks. He had told the guard he was a pianist who couldn’t ruin his hands. Joseph had survived Auschwitz but, debilitated, died in early May 1945, while making his way home.

Clara moved to Cluj and graduated from public high school in 1946. Four years later, she received the equivalent of a master’s degree by passing an exam offered by Victor Babes University in Cluj.

That year she married Paul Knopfler, a survivor from Gurghiu, Hungary. Their son, George, was born on Clara’s birthday in 1955.

Clara and her family, as well as Pepi, who lived with them, immigrated to New York in 1962.

Paul, a pharmaceutical chemist, was killed in an industrial accident in 1991, leaving Clara heartbroken. Months later, her principal — Clara recently had retired from 26 years of teaching — asked Clara to return as a long-term substitute, which she did, until moving to California in 2009, where her son and two grandchildren live.

Pepi died in 1999, at age 101. She was the motivating force behind Clara’s memoir, “I Am Still Here: My Mother’s Voice,” published in 2007. Meanwhile, Clara continues to tell her story.

“This is my mission. Those few who survived cannot live with themselves if they do not speak,” she said. “When this generation is gone, forget it.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.