When it comes to Israel, Jonathan Medved has no interest in watching from the sidelines.

A former political activist and UC Berkeley alum, Medved, a Los Angeles native and Jerusalem resident, was named by The New York Times in 2008 one of the most influential Americans impacting the Jewish state. His life has been one of identifying opportunities — starting small and growing fast.

As a college student in 1973, Medved returned to the San Francisco Bay Area one week before the start of the Yom Kippur War and found a campus awash in anti-Israel sentiment. Motivated to do something, the young Zionist became a campus activist for Israel, eventually becoming the Jewish Agency for Israel’s director of university services in the United States.

Although he’s still an ardent and outspoken supporter of Israel, Medved has come a long way since his undergraduate days, finding a less political means of supporting his beloved country — venture capital crowdfunding.

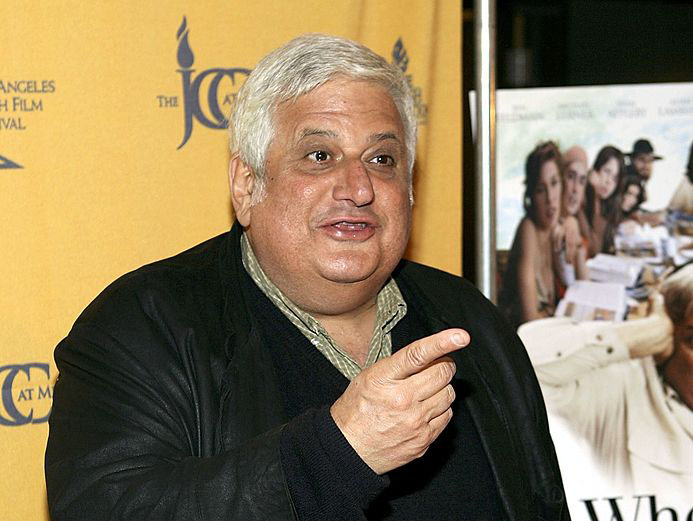

Speaking in December in Santa Monica on what was the second leg of a whirlwind, worldwide tour, the uber-energetic, 58-year-old entrepreneur showcased his latest adventure in the financial world: OurCrowd.

It’s a year-old “equity-based crowdfunding platform” that allows accredited investors to put as little as $10,000 — small for the venture capital world — into a select number of approved and vetted Israeli startups, all of which need cash to grow, and stay afloat, until business operations kick into full gear.

“You are able to take the best of venture capital — the professionalism, the diligence, the protection you get — and combine it with the fun, and discretion, and the freedom, and the low entry price of being an ‘angel’ [who invests after falling in love with a company],” he told a group of 80 at Cross Campus, a shared work space in Santa Monica.

Here’s how it works: An Israeli startup in the early stage of fundraising applies to be listed as a company backed by OurCrowd. Then, a team of analysts studies the ins and outs of the business: When can it expect positive cash flow? How much debt does the company anticipate accumulating? Is the entrepreneur’s vision realistic?

If the startup is brought under OurCrowd’s wings — something that Medved said happens to only 2 or 3 percent of the 100-plus monthly applicants — it may find itself with a potential gold mine of capital. Since Medved launched the company in February 2013, he has helped 31 startups raise $30 million from about 3,000 investors.

During his Dec. 13 presentation, he introduced local entrepreneurs and venture capitalists to several Israeli startups, including Takes and Easy Social Shop. Last year, OurCrowd investors raised $250,000 for Takes, a camera app that allows users to convert a series of photos into video. And since being funded by Medved’s group in 2012, Easy Social Shop, which makes it easy for e-commerce retailers to set up virtual storefronts on Facebook, has gone on to facilitate 80,000 shops listing more than 8 million products.

Jon Warner, a local venture capitalist who came to do some preliminary research on OurCrowd’s startups, said he was most intrigued by Easy Social Shop and “its potential to monetize” Facebook’s user base.

Not just anyone can invest through OurCrowd. Because many countries, including the United States, legally require investors in startups to already have plenty of their own cash, the players putting skin in the game tend to be experienced in identifying people and ideas that have serious potential.

This wasn’t a career Medved sought out. Born in San Diego, but raised in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles, he is one of four brothers in a family that seems to have a flair for jumping head-on into the public square. Michael, who lives in Seattle, is a best-selling author and nationally syndicated talk-show host. Harry is a spokesman for the movie Web site Fandango and lives in the Los Angeles area.

Kicked out of Sinai Temple’s Hebrew school as a youngster, Medved attended Palisades High School and was raised in what he termed a traditional Jewish family.

“This was an idyllic childhood,” he said, reminiscing about his Westside days. “Where I grew up was like ‘Leave It to Beaver.’ ”

Having no clue what he wanted to do professionally — just knowing that he didn’t want to be a spectator — Medved visited Israel for the first time in 1973. The Jewish state had the “Birthright effect” on him long before there was Birthright, and seven years later he made aliyah.

“When everybody saw me going off to live in Israel, they said, ‘OK, well, he’s an idealist, he’ll be poor,” recalled Medved, who has a thick beard and wears a kippah.

In 1980, he said he still had no direction, other than knowing that he wanted to be “an actor and a player” in the Israeli experiment. Then, in stepped his late father, David Medved, a physicist who, in the 1950s, developed technology to destroy midflight intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Trying to get a fiber optics communications startup off the ground, the elder Medved couldn’t have known that asking his son for help would lead to a successful venture capital career for the latter.

Even while working with his father, Medved thought his future would be in activism. That is, until an Israeli scientist he was dealing with on the project spoke to him like a fellow Israeli — no subtleties, no nonsense.

“What a waste,” the scientist remarked in Hebrew after speaking with Medved about his activist hopes.

Surprised, Medved shot back, “Ani boneh et ha medinah” (I’m building the country).

“What your father is doing is real Zionism,” responded the scientist. “Go build a factory for fiber optics.”

And in 1982, the father-son duo did just that, subleasing space in a Jerusalem building used by glassblowers.

“People didn’t know what fiber optics were,” Medved said. “They’d see the glassblowers and figure that must be [fiber optics].”

For the next eight years, Medved built up the company, Meret Optical Communications, eventually selling it in the early 1990s to Amoco Corp., which later merged with BP.

A few years later, he started the venture capital fund Israel Seed Partners in Jerusalem. It went on to invest nearly $300 million in startup Israeli tech and life-science firms, and proved to be great preparation for OurCrowd.

By the time Medved temporarily exited the venture capital world to found the mobile social apps company Vringo in 2006, he had invested in more than 100 Israeli startups, helping 12 of them reach a net worth of more than $100 million each.

“To sit and listen to people’s dreams and then to be, in a small way, able to help them make it come true is the most wonderful job,” he said.

Unfortunately, he admitted, helping businesses grow, sometimes, means doing some less pleasant things.

“God forbid, if the business is not meeting its projections, you’ve got to cut the budget, which means fire people.”

Medved sits on the boards of many of OurCrowd’s startups, and for those that he doesn’t, he helps recruit experienced mentors, doing the best he can to make sure all of his companies succeed.

Medved knows that playing in the Israeli financial world also means factoring in risks unknown to many investors around the world, namely the volatile nature of the region.

“People have learned to discount this,” he said. “I’m not the only one who has somehow just learned to live with this kind of existential risk. It’s Microsoft; it’s Cisco; it’s Google; it’s Facebook.”

Following the event in Santa Monica, Medved was able to sum up his philosophy succinctly by referring to Pirke Avot:

“Who is wise? [He] who sees the yet-to-be.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.