“The State of Israel may be regarded as the quintessential science fiction (SF) nation,” write Sheldon Teitelbaum and Emanuel Lottem, the co-editors of “Zion’s Fiction (Mandel Vilar Press), “the only country on the planet inspired by not one, but two seminal works of wonder: the Hebrew Bible and Zionist ideologue Theo-dor Herzl’s early-twentieth century utopian novel, “Altneuland (Old New Land).”

Yet it is also true that the 17 stories collected in “Zion’s Fiction” reflect the here and now of modern Israel. “This book will pry open the lid on a tiny, neglected, and seldom-viewed wellspring of Israeli literature, one we hope to be forgiven for referring to as ‘Zi-fi,’ ” write the co-editors in an introduction to the anthology. “We define this term as the speculative literature written by citizens and permanent residents of Israel — Jewish, Arab, or otherwise, whether living in Israel proper or abroad, writing in Hebrew, Arabic, English, Russian, or any other language spoken in the Holy Land.”

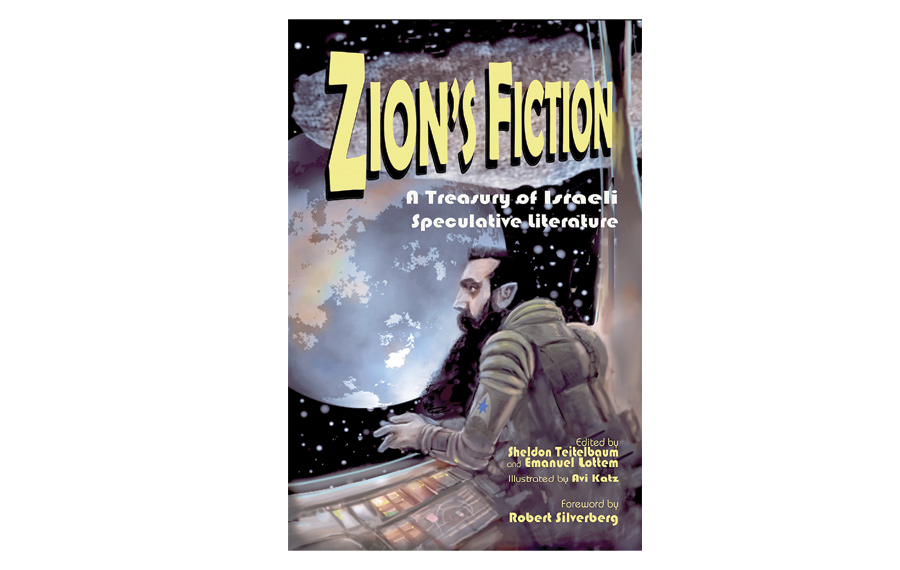

The introduction to “Zion’s Fiction” and an introduction by Robert Silverberg, one of the living masters of the SF genre, are admirable works of literary history and commentary in themselves, and they provide an illuminating context for the stories that follow. But the stories, of course, are the real attraction, and “treasury” is exactly the right word to describe what we find in the collection. Buried in these fascinating exercises in imaginative fiction are glimpses of the anxieties and aspirations of the real Israel.

“The Smell of Orange Groves” by Lavie Tidhar, for example, imagines a future version of Israel as a poly-ethnic nation that includes not only Arabs and Jews but men and women whose ancestry reaches all the way to Mars. Their religious leaders now include such new-fangled authorities as Saint Cohen, the Oracle of the Others, and Brother R. Patch-It of the Church of Robot. “The question of who is a Jew had been asked not just about the Chong family, but of the robots, too, and was settled long ago,” muses Boris Chong, the hero of the story, a Russian-Chinese Jew who finds himself inexplicably haunted by dreams of the far-distant era when Tel Aviv did not yet exist and the place where he lives consisted of “orange groves, and sand, and sea.” After thrusting us into a strange new world, the author reminds us that sentimental memory provides no relief from the terrors of the world we already knew.

“Buried in these fascinating exercises in imaginative fiction are glimpses of the anxieties and aspirations of the real Israel.”

In “The Believers,” Nir Yaniv describes the sudden appearance of God on Earth in the guise of a judge who inflicts sudden and gruesome death on anyone He judges and finds wanting. All too many modern Jews, it turns out, are deemed to be worthy of divine punishment. The narrator, for example, recalls the night when he and his girlfriend could no longer wait for marriage before sleeping with each other. “A weird smell woke me up in the morning,” he recalls. “Just beside me, in bed, a gray-red-purple sack, moist, dripping went. Still twitching. Fluttering about. My girlfriend, turned from the inside out.” So God is proven to be utterly real and highly dangerous, but the narrator turns out to be just as judgmental. Like Abraham and Moses, he is perfectly willing to stand up to God.

“I have always believed in God,” he tells us. “It’s about time that He started believing in me.”

Not every story is quite so theological or so apocalyptic. “Death in Jerusalem” by Elana Gomel begins as a simple and poignant boy-meets-girl story, but the woman called Mor senses something strange about her b’sheret, David. “His kisses were sterile; his mouth tasted of nothing.” When they marry in a civil ceremony in Cyprus, and she meets his family, she sees them as avatars of death by plague, by suicide, by old age. The life that Mor and David live is normal enough (“They watched Netflix and ate dinner”), but something threatening is always just below the surface. Eventually, Mor is forced to confront a dire presence that “was there when Neanderthals scattered ochre around the skeletons of the eaten ones … when shamans withered babies in their mothers’ wombs and flayed men alive without even touching them.” The ending owes more to “Rosemary’s Baby” than to anything in the Tanakh, and some readers will be reminded of the ghost stories that Isaac Bashevis Singer loved to tell.

Many of these science fiction stories, however, can be understood as a kind of modern midrash. The Bible’s talking donkey was Balaam’s ass, of course, but we are introduced to his modern counterpart in “My Crappy Autumn” by Nitay Peretz, a wildly comic parody that features a Yiddish-speaking and wisecracking donkey named Tony. “Believe me, everyone’s an ass,” Tony insists. “But at least this ass knows what he’s talking about.” The character who tells the tale is Ido, whose girlfriend has dumped him and sent him into suicidal despair. His weapon of choice is a chrome-plated Jericho Magnum: “When it comes to death, only Made in Israel will do.” But he is diverted when a UFO lands in Yarkon Park in Tel Aviv, where it is surrounded by “three Merkava Mark II tanks and one Chabad Mitzvah tank.” Ultimately, the lesson that Ido

learns from Tony is reminiscent of Balaam and his famous ass: “Some Jews have the heart of a donkey, and some donkeys have a Jewish heart.”

Science fiction and fantasy may be understood as a refuge from the harsh reality of the world in which we find ourselves. But, as “Zion’s Fiction” shows us, it actually seeks to show us a way to solve our problems rather than just hiding from them. “SF dreams (and nightmares) are products of the imagination, but they are inspired by reality,” writes Aharon Hauptman in an afterword. “If humans fail to understand our potential futures, our alternative realities, it is mostly due to the failure of imagination.” When Hauptman argues that “an SF story is a thought experiment about alternative realities,” he is defining exactly what all of us need to find a path forward.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.