David Kipen is a real mensch. He is the celebrated founder of Libros Schmibros, the nonprofit lending library in Boyle Heights. As the former literature director of the National Endowment for the Arts, he supported the work of countless writers and artists, and he did the same during his tenure as the book editor and critic of the San Francisco Chronicle. Today, he continues to play a crucial role in California arts and letters as a writing instructor at UCLA, a book critic for Los Angeles magazine and a critic-at-large for the Los Angeles Times.

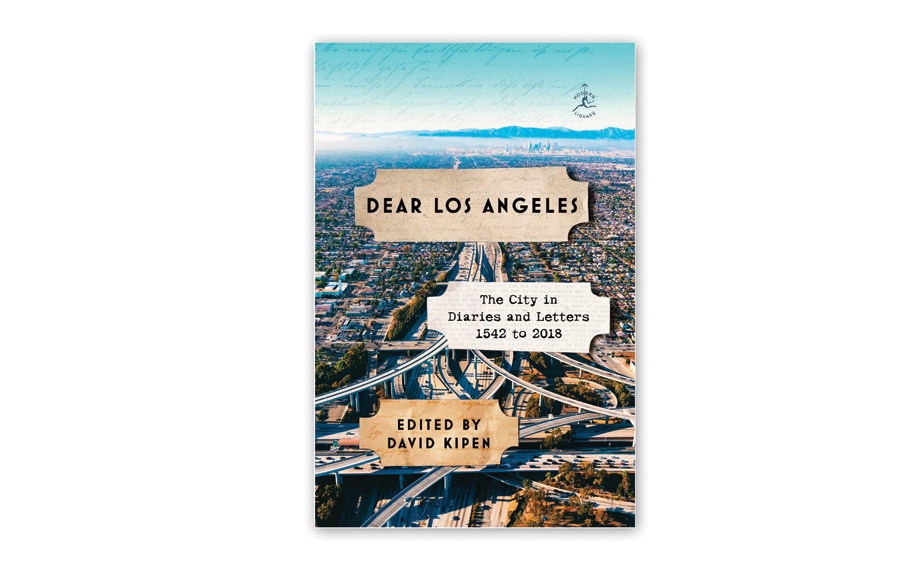

Now Kipen has made yet another contribution to the literature of Los Angeles, something audacious, unique and valuable. “Dear Los Angeles: The City in Diaries and Letters, 1542 to 2018” (Modern Library) is an anthology of musings about Southern California that span four centuries, each one a little gem of observation or reminiscence or commentary and, taken together, a glittering constellation of lapidary prose. Somewhere in those points of light, we begin to see the shape and meaning of the elusive place where we live.

“This book is a collective self-portrait of Los Angeles when it thought nobody was looking,” Kipen explains. “Joyous, creative, life-giving. Violent, stupid, inhospitable to strangers. Cerebral, melancholy. Funny.”

The entries for Jan. 1, for example, start with the pioneering attorney and jurist Benjamin Hayes (1853) and end with contemporary urban activist Aaron Paley (1985): “What a city! Widen the streets! Tear down the past! Destroy the trees.” And the entries for Dec. 31 start with an 1889 snippet from Charles Lummis, whom Kipen describes as not only a newspaperman, librarian and archaeologist but “also a booster, self-promoter, windbag, mountebank, and rapscallion,” and ends with English expatriate author Christopher Isherwood, the bard of Santa Monica Canyon (1975): “What I am trying to say is that it is doubtless easier to feel that God is the only refuge when you don’t have any human being to love and be loved by. But I do.”

Kipen is unapologetic about what he calls its “hiccupping” principle of organization: “One step forward, two centuries back — the perennial, quixotic spectacle of L.A. forever finding fresh mistakes to make.” He includes many luminaries of Western letters, ranging from Richard Henry Dana to Nathanael West to Jonathan Gold, although he confines his selections to diary entries and letters with only an occasional blog posting or other published work. As if to make the point, we read a line written in 1903 by the Californio diarist Don Juan Bautista Bandini: “Bought a book for a diary in Los Angeles,” and Anaïs Nin’s private affirmation of “my belief that if one goes deeply enough into the personal, one transcends it and reaches beyond the personal.”

Even so, the principle of selection produces an extraordinarily rich and diverse collection of writing. The authors range from Fray Juan Crespi to Albert Einstein to Brian Wilson, from Helen Hunt Jackson to T.S. Eliot to Octavia Butler, and include such odd literary bedfellows as Simone de Beauvoir and Richard Feynman, George Patton and Groucho Marx, Charlton Heston and Allen Ginsberg, Sylvia Plath and Eric Idle, Rudolf Schindler and John Lennon. Kipen even finds room for a fateful, if hateful, remark about Robert F. Kennedy by Sirhan Sirhan in advance of their rendezvous with destiny at the Ambassador Hotel.

Kipen’s discerning eye has sought out a few deserving figures who otherwise are mostly forgotten. To be sure, he quotes the famous photographer Edward Weston: “I am disgusted this morning for not having slept longer. Probably I overworked yesterday, having made 12 enlargements from as many negatives on an order. It will bring me $120, then I’ll sleep better.” But he also includes Charis Wilson, Weston’s much-photographed muse and model, whose nude images are remembered but whose words are forgotten: “Through San Clemente — all white blgds. with red tile roofs — such an uncomfortable looking place — one rebel gas station has painted green bills on his window and we bet the town council will soon see to him.”

“This book is a collective self-portrait of Los Angeles when it thought nobody was looking.” — David Kipen

Kipen is respectful and savvy enough about Los Angeles’ literary and journalistic traditions to include writers whose bylines have long since disappeared from our public prints. “Medieval castles will tumble and antique oriental temples will fall,” wrote beloved L.A. Times columnist Jack Smith in 1959. “It will be the end of a make-believe world — the 176-acre acre; false-front world of film sets on the famed 20th Century-Fox lot … will be razed and cleared to make way for a $400 million complex of steel and concrete towers to be known as Century City.”

Indeed, and on a strictly personal note, I am moved to point out that my late father, Robert Kirsch, is one of the writers whom Kipen invokes in “Dear Los Angeles.” Robert Kirsch was the literary pole star of Los Angeles for the four decades during which he wrote daily book reviews in the Los Angeles Times, but his name has not appeared in print since his death in 1980, except when one of his reviews is quoted in an obit or when the Times bestows the lifetime achievement award that bears his name. I can imagine no greater tribute to my dad than what Nin wrote in the letter to him that Kipen quotes in “Dear Los Angeles”: “Of all the things which have been said, written about the Diaries, you wrote what has the deepest meaning for me — you answered as only someone who is a writer and a critic and a human being could.”

Jonathan Kirsch, attorney and author, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.