More than 100 men and women have served on the Supreme Court, but only one can be fairly described as a rock star.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s ascent into popular culture was confirmed in 2015 with “Notorious RBG,” a playful book by Irin Carmon and Shana Knizhnik, and a 2018 documentary film titled “RBG.” Her face and figure are displayed on mugs and T-shirts, Halloween costumes and Christmas tree decorations, removable tattoos and children’s coloring books. We can even watch her workouts on YouTube, and when Stephen Colbert tried to replicate her demanding exercise regimen, he declared himself defeated by its rigor.

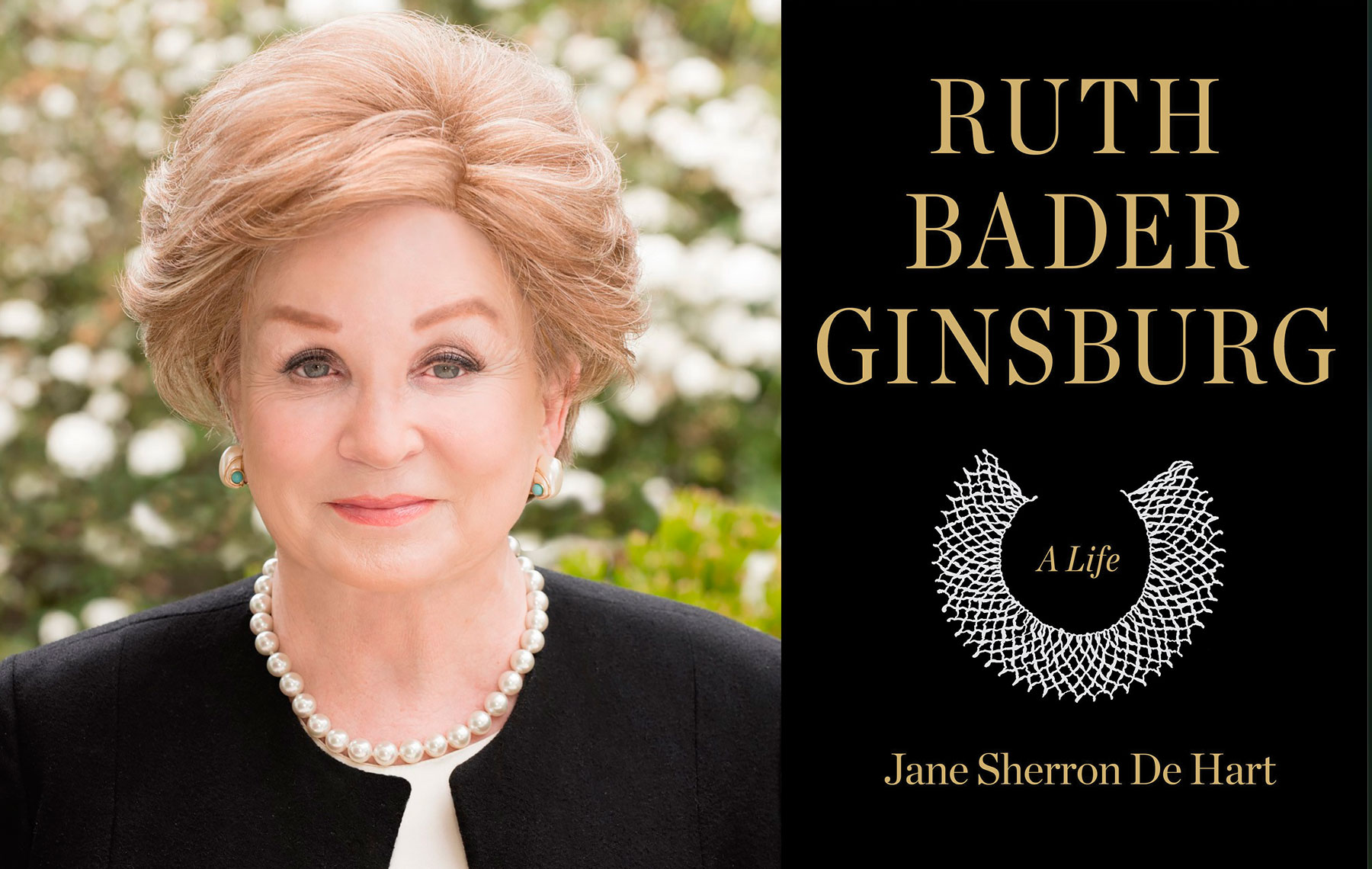

Now her life story is told in full by Jane Sherron De Hart, a scholar of American history and women’s studies whose academic appointments have included the University of North Carolina and UC Santa Barbara. De Hart has invested some 15 years in the research and writing of “Ruth Bader Ginsburg: A Life” (Knopf), including a series of annual interviews with Ginsburg, and she succeeds in showing us that the 107th person to be appointed to the Supreme Court is much more than a pop culture icon.

“… Ginsburg has made her mark not only on the jurisprudence of the United States but also on American society and popular culture more broadly,” De Hart writes, describing the remarkable breadth of her achievements in public life. “But the portion for which she is most remembered began with her efforts to make her chosen profession more welcoming to women at a time when it was overwhelmingly white and male.” And yet the values she embraces and the role she has played in putting them to practice are even more expansive. “Her pursuit of equality has been capacious, encompassing not only women but also men, African Americans, Hispanics, gays, immigrants, the poor, and the disabled.”

The life story begins in 1933, when Joan Ruth Bader was born at Beth Moses Hospital in Brooklyn to a mother and father who had each emigrated from Europe, her father (Nathan Bader) from the Ukraine and her mother (Celia Amster) from Poland, although Celia was “still in her mother’s womb” when the family arrived in the United States. Ginsburg’s upbringing was infused with Celia’s “boundless zeal and perfectionism” and her emphasis on “what it meant to be Jewish, American and female.” Thus, for example, Ginsburg’s childhood birthday parties were held each year at the Pride of Judea orphanage, where Ginsburg (known by the nickname “Kiki”) was taught that “even her own very modest economic advantages obliged her to share with those less privileged.”

All three of these themes, as De Hart shows in compelling detail, can be traced from her childhood reading to her jurisprudence on the Supreme Court. “Essential to her desire to make We, the People more united and our union more perfect is her Jewish background,” de Hart explains. “Tikkun Olam, the Hebrew injunction to ‘repair the world,’ had profound meaning for a thoughtful young Jewish girl who grew up during the Holocaust and World War II. So, too, did the phrase above the entry to the first chambers that she occupied as justice – Tzedek Tzedek tirdof (Justice, justice you shall pursue).”

“Essential to her desire to make We, the People more united and our union more perfect is her Jewish background.”

— Jane Sherron de Hart

De Hart makes the case that Ginsburg would deserve a place in history even if she had never been elevated to the Supreme Court. Starting as a Rutgers law professor and an attorney for the Women’s Rights Project of the ACLU, she served on the front lines of the struggle for gender equality under the law. “In retrospect, Ginsburg’s embrace of feminism seems to have been an easy fit for a woman who, in many respects, ‘walked the walk’ before the street was named,” De Hart quips. Thus did Ginsburg turn herself into “‘a tiger for the Cause’ — ‘a quiet tiger, a moderate, sensible tiger, but a fearsome tiger’ nonetheless.”

Then, too, we are shown the flesh-and-blood Ginsburg, as when her daughter, Jane, recalls her mother’s “tenacity on matters of posture, tidiness, or diet,” De Hart writes. “Recalling her mother’s eagle eye for candy wrappers in the waste basket, she added, ‘Her searches and seizures of my childhood debris showed that Fourth Amendment principles held no place of honor in our household order.’ ” On significant occasions, such as an oral argument before the Supreme Court, Ginsburg would wear an item of jewelry that had belonged to her beloved mother. Ginsburg’s son, James, wrote a poem on her 50th birthday that captures her work ethic: “On three hours’ sleep you’re not always fun/But that’s okay, says thy sweet loving son.”

Case by case, decision by decision, De Hart shows how Ginsburg’s courtroom advocacy eventually leveraged her into a fateful judicial appointment to the Court of Appeals by President Jimmy Carter in 1980. Thirteen years later, hailing her “achievements, decency, humanity and fairness,” President Bill Clinton elevated her to the high court. While she was “fated to serve as a member of the minority among ever further right-leaning colleagues,” as De Hart puts it, and now finds herself on the wrong side of a baked-in 5-4 majority on the Supreme Court, De Hart insists on taking the long view.

“[S]he is too familiar with history to assume that progress is linear,” De Hart concludes. “Like liberty, equality, she believes, is never really won, but has to be fought for by each generation.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.