While reading Philip Roth, even an avid fan of his sacrilegious style and elegant prose thinks about Gershom Scholem’s critique of “Portnoy’s Complaint”: “This is just the book that anti-Semites have been waiting for.”

Roth may have been one of the first American writers brave and talented enough to portray the Jewish community as it was and not how he wanted it to be, but once he opened the Pandora’s box of sexually unfulfilled Jewish male protagonists surrounded by morally scrupulous characters, other writers followed suit.

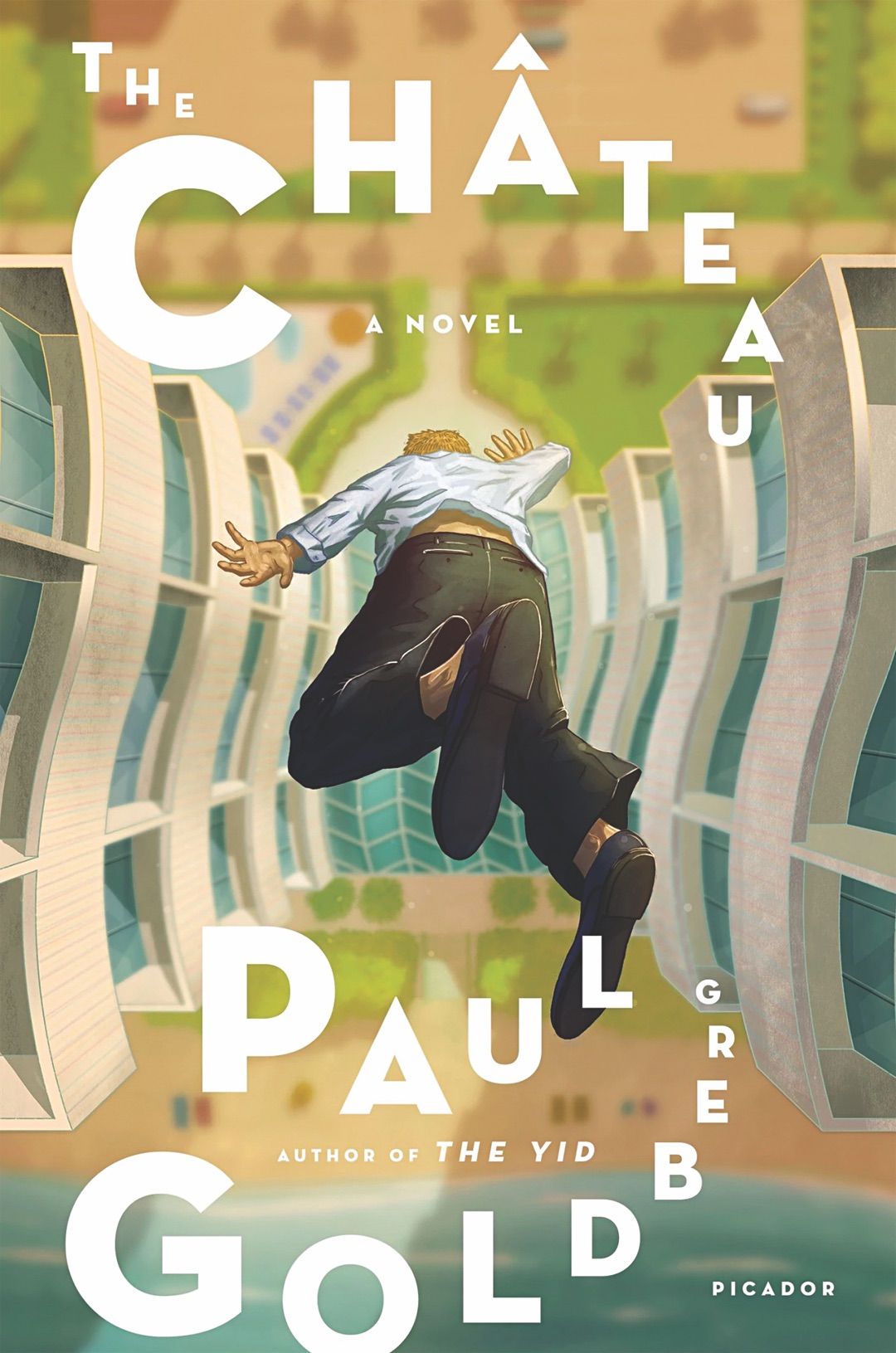

Paul Goldberg’s novel “The Chateau” centers around scheming, crooked Jews, most of whom are Russian and elderly retirees living in Miami. The novel reads like a classic whodunit, but the super villains are condo board members, the victims are Jewish retirees, and the big clue that helps the retirees crack the case is the fact the elderly are given kickbacks in the form of white Lexuses (Lexi?). The elderly gentlemen steal, bug one another’s rooms and flood parts of their own building to access insurance money. Goldberg sums up the depressing life cycle of the retired Jew living in Florida:

Let’s say you devoted your life to screwing other people. You break no more laws than you have to. You avoid being disgorged, you build up a goodly stash. You move to Florida. You get f—– by your condo’s BOD. Your stash gets drawn down. You try a new fraud, it fails. The world is changing; you are losing your touch. You move on to a lesser place … you might die in the middle of it. You might want to. You will make room for fresh, idealistic sixty-seven-year-olds to take their turn at the good life by the sea.

It is Goldberg’s bleak idea of a Shylockian Jewish circle of life.

The question being asked in this book is: “Has the world become a big crooked condo board?”

Most characters in this book get negatively stereotyped, but if they are not being typecast, they are made up of a strange amalgam of hobbies and peccadilloes that give the storyline a surrealist tinge. The book’s sleuthing Jewish hero, who generally is referred to as Bill throughout the book, is nebbish, unemployed and depressed. He tries to save others from drowning despite the fact that he himself can barely keep afloat. At age 52, he has been a successful science reporter for decades, but is also an avid antique furniture collector and architecture enthusiast. He has only $1,403.86 in his checking and savings accounts combined, but in his free time, he walks around Miami studying Morris Lapidus architecture and picking out rotting Richard Schultz chaises by the pool.

Bill’s Russian father, Melsor Yakovlevich Katzenelenbogen, is an overblown and cartoonish foil for his son, and feels more at home as the villain of a spy novel. Goldberg seems to be aware of these exaggerations because Bill describes his father as what you get “if you cross American fraud with Russian literature.” The vodka Melsor keeps in his home is a perfect metaphor for the character’s transparent, tasteless facade:

The bottle is full, but not sealed. Bill has the capacity to interpret this: Grey Goose, a French vodka, bespeaks prosperity and generosity. That’s a good thing. Its cost is a bad thing. The solution: Procure a bottle of Grey Goose, consume its contents, then keep the bottle in perpetuity and continue to fill it with something more in line with what you wish to spend. Alas, Grey Goose is a canard.

Bill’s disappointment in the undrinkable contents of the bottle mirror his disillusionment with Melsor. He wants his father to finally invest in being a proper parental figure, but Melsor is not willing to spend that kind of time and money on his son. He prefers to have the appearance of a relationship without really investing in its contents.

The beginning of the story is developed so that you believe the protagonist will spend the entire novel on the search to solve the mystery of why his college roommate, Zbignew Wronski, fell or jumped to his death. In fact, very little of the novel is dedicated to this onomatopoeically named character. Instead, Goldberg executes a bait and switch, because we are reeled in by a murder mystery when the novel actually focuses on an objectively less sexy case of insurance fraud.

To better understand this book, it helps to realize that “The Chateau” is a product of the 2016 American presidential election. It was released in February 2018, which means that — taking into account the writing, editing and publishing timeline — the novel was likely conceived of when Donald Trump was not even the official presidential nominee. In his acknowledgements, Goldberg thanks the “semi-fictional character the Chateau residents call Donald Tramp for giving this book urgency, providing the macrocosm for my microcosm, and inspiring me to write like the wind …”

The novel clearly began as a book about a journalist trying to find the truth behind his roommate’s possible murder. But Goldberg rushed to publish as it morphed into a saga of disillusionment and anger in response to American politics taking an unexpected turn.

Goldberg’s book could have been much stronger and integrated had he not shoehorned together two disparate plots and rushed to publish while Americans were still obsessed with the political division in their country. Without Zbig’s death, one can imagine a very different book that was more about a degenerate father and his estranged son. Melsor’s character feels like he entered the text as an afterthought but ended up slowly taking over the book as Goldberg responded to a similar figure dominating the news cycle.

The question being asked in this book is: “Has the world become a big crooked condo board?” The analysis of the scheming board of directors (BOD) is really Goldberg’s way of trying to understand the “crooked” American political system and his disillusionment with his own country.

As many right-wing, elderly Jews and their left-wing American offspring have tried to build bridges of understanding in the aftermath of the American election, the fictional Bill finds himself looking at the Chateau, a microcosm of Republican America and asking himself: “Who are these people? Bill understands their language, but they are nothing like him.” He has never understood the right wing in his country, which includes his father, so he decides to bridge the gap he has discovered between himself and America, beginning with his dad.

At the Chateau — the once grand and now dilapidated building in which his father lives — he casts himself as a Noah-like figure who will discover what is beautiful and try to save this building that is being destroyed. He first describes his father’s old condo as “an epic disaster. A waterlogged, crumbling building on this stretch of the Golden Coast.” There are so many areas of the building that are flooded, but Bill looks for the beauty in it and begins to refer to the Chateau as “the lost ark.”

“The Chateau’s” most redeeming quality and what truly saves the text is its narrator. The book does not have a great deal of dialogue and most of the action is described by a sarcastic, dry narrator who seems to be Bill talking about himself in the third person. The style of narration is reminiscent of that in the background of a modern telenovela like “Jane the Virgin.” The characters never really get to laugh at or digest some of their more complicated feelings and experiences, but the reader and narrator try to do it for them. Thanks to the narration, the reader gets a very intimate view of the protagonist despite the fact that Bill barely shares anything with the reader or with himself. He lets the narrator discover truths for him that his character never digests. This style of narrator allows the reader to sympathize and relate to Bill as if he were telling the story himself, but also remains consistent with his standoffish antisocial personality because the real Bill would never be sharing this story with others.

Bill, Melsor and the rest of “The Chateau’s” cast of characters do not truly look within themselves and think about how and why they have gotten stuck in their respective predicaments, and maybe there lies the rub. Goldberg is struggling with the divisiveness in America today and Bill may be on what he calls an “existential investigation,” but while Bill studies the culture around him, he does not try to change himself. Reading the book makes one feel as though the solution to our country’s struggle might be for each of us to look deep inside ourselves and have a willingness to change. If all else fails, at least there will always be vodka.

Na’amit Sturm Nagel teaches English literature at Shalhevet High School in Los Angeles.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.