A couple of millennia passed between the occupation of ancient Judea by a Roman army and the founding of the modern State of Israel. For that reason, the body of Jewish religious law that is collected in the halachah had little to say about war until the mid-20th century, when modern rabbis encountered the new and startling realities of a Jewish state and a Jewish army.

To understand how Judaism copes with war, Robert Eisen, professor of religion and Judaic studies at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., focused on the writings and teachings of five influential rabbis in the religious Zionist movement, ranging from Abraham Isaac Kook (1865-1935) to Shlomo Goren (1918-1994), the first chief rabbi of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and “the only one of our rabbinic figures to have actually served in the Israeli army and engaged in combat.”

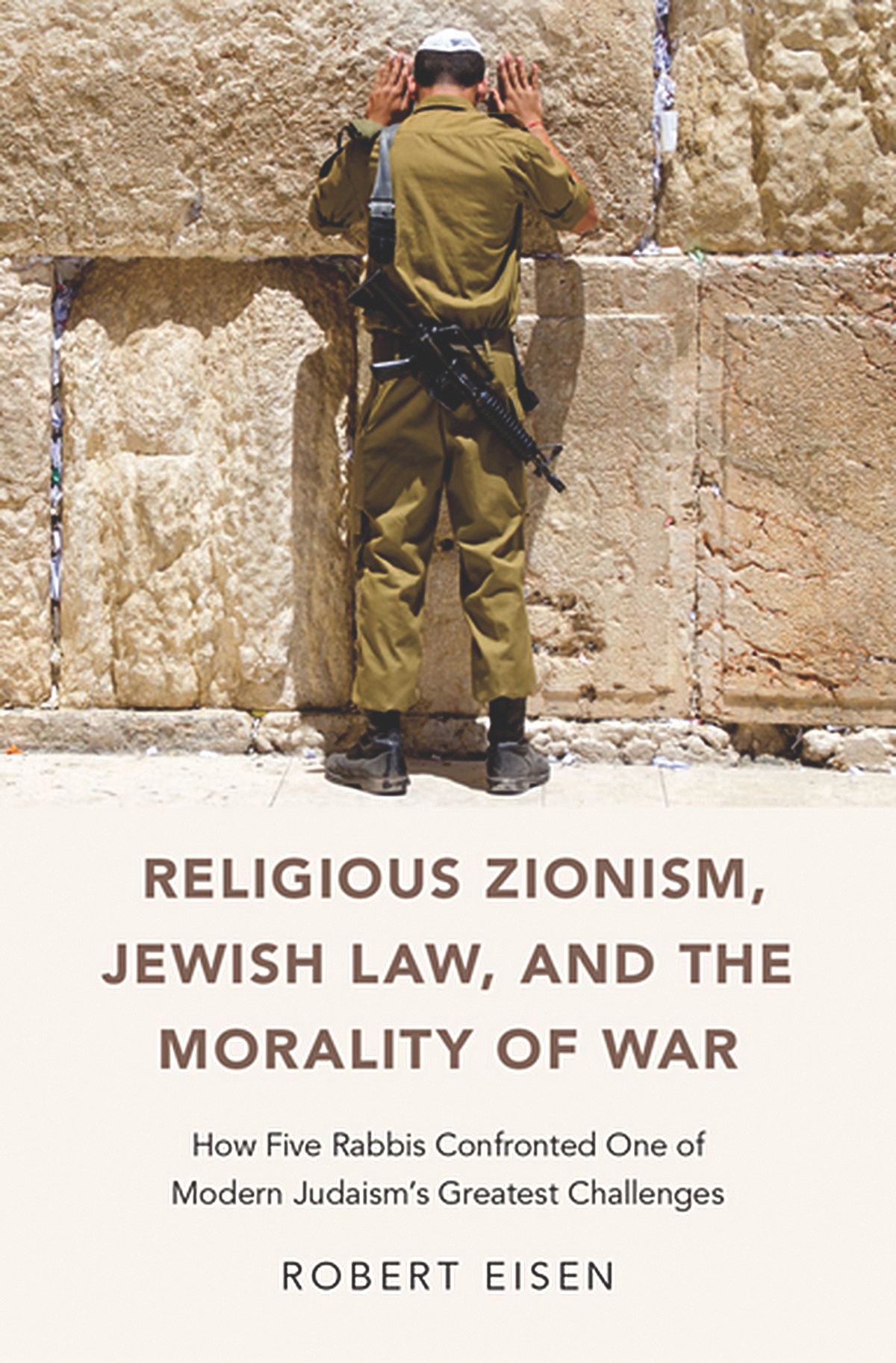

The result of Eisen’s remarkable enterprise is “Religious Zionism, Jewish Law, and the Morality of War: How Five Rabbis Confronted One of Modern Judaism’s Greatest Challenges” (Oxford). Unlike much else in the ponderings of the rabbis and sages, what they have to say about the ethics of war are urgent, enduring and more timely today than at any other time since statehood.

“In fact, Israel has never known a time when it has been entirely free of war,” Eisen points out. “Even when not engaged in actual war, Israel has always had to prepare for the next war on the presumption that it is not likely to be far off.”

Conscription, the risk of civilian casualties, the moral distinctions between defensive and offensive wars and between “mandatory” and “discretionary” wars, and the conflict between the duties of a combat soldier and the duties of a pious Jew are only some of the challenges faced by a Jewish state that is both sovereign and observant. All of them were considered in detail by the rabbis whom Eisen has studied. But the rabbis go far beyond the question of what is permitted and what is forbidden on the battlefield and grapple with the ultimate theological questions.

“The rabbis in this community have had to ask why God has required Jews to engage in violence in order to return to their homeland,” Eisen explains. “This question has in turn been connected to the larger issue of God’s plan for history and the role of the state of Israel in that plan. Does the establishment of Israel have messianic significance, and if so, what role does violence play in that enterprise?”

From the beginning of statehood, as we learn in Eisen’s scholarly but also superbly written book, some religious Zionists advocated the creation of medinat ha-torah — “a state according to Torah” — but it remained only aspirational “because Israel’s secular public had no interest in it” and because “the religious Zionist camp did not have a clear idea of what medinat ha-torah meant.” Indeed, as Eisen writes, “it was not clear from a halachic standpoint that such a state could go to war at all, even for defensive purposes.”

“Israel has never known a time when it has been entirely free of war.” — Robert Eisen

Yet war confronted the Jewish state with “facts on the ground.” In 1948, when a young man named Tuvia Bir, a member of the Ezra youth movement, posed seven questions about service in the Haganah (the former Jewish paramilitary organization) to Rabbi Isaac Halevi Herzog (1888-1959) — including a question about fighting on the Sabbath — Herzog declared that he found the very question to be incomprehensible. “In the present situation, if we did not volunteer for defensive operations, then, God forbid, the danger of annihilation would be expected for all of us,” he responded. “What alternative do we have? To surrender to the enemy?” Like Kook, Herzog ruled that, as Eisen explains, “everyday Halakhah and wartime Halakhah are different from each other.”

The touchstone for all of the rabbinical discourse about war is the Torah, which provides an abundance of examples of Jews at war. We are told in the Book of Numbers, for example, that Moses commanded the Twelve Tribes of Israel to conduct a war of extermination against the Midianites to punish them for luring the Israelites into idol-worship. Rabbi Sha’ul Yisraeli (1910-1995) cites the biblical incident as legal precedent for the decision of the Israeli government to send commandos on a rescue mission to Entebbe in an operation that “risked not only the lives of the Israeli commandos but also the lives of the hostages themselves.”

For Yisraeli, the mission was not merely heroic but holy — an act of Kiddush hashem, the “sanctification of the divine name” — because the hijackers had freed the non-Jewish passengers and held only the Jews as hostages. “In singling out the Jews, the hijackers were publically targeting the Jewish people and thus targeting God as well,” Eisen explains. “R. Yisraeli applies the notion of kidush ha-shem to the Midianite war, all subsequent wars initiated by enemy nations, and the Entebbe situation.”

I doubt that such rabbinical musings come up in the war room of the IDF or, for that matter, the front lines where Israeli soldiers actually fight. In fact, Rabbi Goren recognized that nonobservant Jews have always represented a majority of the Jewish population in Israel, and he “stated quite openly that a conscious effort should be made by rabbinic authorities to come up with halakhic positions that would be acceptable to the secular population in Israel.” Above all, Goren came to recognize that there is an inevitable and irreconcilable tension between “the need to wage war and the goal of seeking peace, between the imperative to defeat Israel’s enemies and the obligation to be sensitive to the moral dilemmas war raises.”

Nowadays, “wartime Halakhah” is increasingly relevant, not only because Israel is always at risk of war but also because observant (if not ultra-Orthodox) Jews are serving in the IDF in ever greater numbers. Eisen points out that religious Jews, who represent only 10 percent of the population of Israel, “made up 20 percent of the soldiers in infantry brigades” by the 1990s, “and among combat lieutenants and captains, the ratio of religious to secular was two to one.” So Israel is closer to being a medinat ha-torah than it has been at any time since the pioneering generation of secular Zionists like Ze’ev Jabotinsky and David Ben-Gurion.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.