Denial just ain’t what it used to be.

Maybe it’s only me, but as recent news has delivered one gut punch after another, it’s been feeling like magical thinking has lost its mojo.

Case in point: Though I know Donald Trump is pathologically void of empathy, who can process a truth as dark as that? We’re not talking about a Batman villain here; this is the effing president of the United States. So as a coping mechanism, my psyche threw an invisibility cloak over his immorality. It didn’t always work, but it came to a dead stop when neo-Nazis – “some very fine people” – marched and murdered in Charlottesville. I plumb ran out of the strategic ignorance necessary to pretend he’s not complicit in evil.

Or take nukes. (Please.) By all rights, nuclear blackmail, nuclear terrorism and accidental nuclear war should have been giving me nightmares for years. But the human capacity for compartmentalization as a way to adapt to the unthinkable did a pretty good job of protecting me from that fear. I don’t know whether, on their own, Kim Jong-un’s accelerating bomb and missile tests would have blown through my soothing self-delusion, but Trump’s crazy rhetoric has undeniably exposed how short-fused those scary scenarios are.

Magical thinking has also Photoshopped my image of the internet. The web’s seductive marvels have had a way of distracting me from mounting evidence of the destruction it enables. But in light of what’s been happening, it’s high time for me to kiss the last vestiges of internet triumphalism goodbye.

Last week the consumer credit-reporting company Equifax revealed that 143 million Americans in their database – half the country – may have had our Social Security and drivers license numbers compromised, as well as the keys to our credit card and bank accounts. Face it: Cyber-security sucks today, and it will suck tomorrow. If you believe your personal data can be reliably protected from hackers, identity thieves, blackmailers, spies, governments, trolls, gamer guys, mean girls and Julian Assange, there’s a Nigerian prince who wants to wire $10 million to your bank account I’d like to introduce to you.

Also last week, the New York Times reported that a cyber-army of counterfeit Facebook and Twitter accounts controlled by impostors linked to the Kremlin had been “engines of deception and propaganda” during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, spreading fake anti-Clinton news, pro-Trump memes and stolen Democratic email to targeted American voters. Facebook – having repeatedly denied it – also disclosed that Russian operatives had bought $100,000 in anti-Clinton ads that may have reached as many as 70 million Americans. Here’s a sobering fact: The digital tools already exist, and are getting better all the time, needed to create convincing counterfeit videos of anyone saying anything, and to confect bogus news stories and brand them as trustworthy journalism. Media literacy and critical thinking have never been more urgent, or up against worse odds.

It’d be comforting to think that companies like Equifax and Facebook have learned their lesson and from now on will deploy the technology needed to beat the devils. But believing what’s comforting in the face of ample prior behavior to the contrary is the definition of denial. Counting on Internet providers to voluntarily embrace an opt-in requirement that respects consumer privacy, like counting on a technical fix for security flaws and propaganda targeting, is the triumph of optimism over precedent.

I’ve clung to such optimism; even if I turn out to be wrong, isn’t that preferable to always fearing the worst? But these days the difficulty of turning a blind eye to reality is taxing my talent for self-deception.

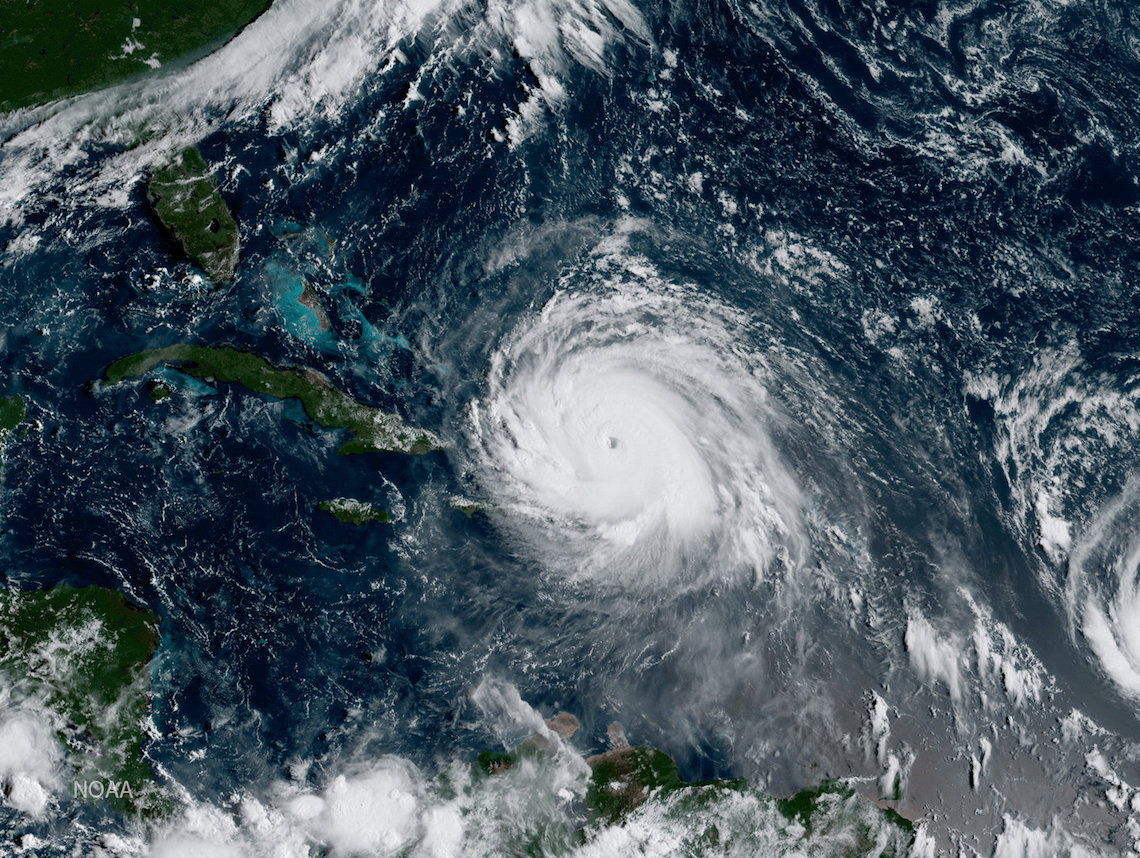

Hurricanes have been dominating the news lately, and few events test the strength of denial as frontally as disasters. But while Harvey and Irma have held news networks hostage – with reason: danger is a magnet for attention – it’s the 8.1 earthquake off of Mexico last week that has me still shaking. I’ve lived in Southern California for a long time, and though earthquakes sometimes drop off my radar screen, I’m periodically conscious enough of their risks that I’ve taken disaster preparation to heart. The proximity of the Mexican quake refocused me on the seismic vulnerability of my everyday life: I checked my battery and water supply. But it also, unexpectedly, laid bare a deeper denial I usually bury fairly successfully, if unconsciously.

I carry around, but rarely examine, a point of view about the relationship between the horrors of natural disasters and my notion of God. I know no God sends these hurricanes, earthquakes, fires and floods. I’m secular, so I don’t require an intricate theodicy to acquit an omnipotent God of capricious cruelty or to sentence a sinful humanity to suffering. But I also don’t experience the universe as arbitrary and meaningless; I experience awe at the mystery of existence, and gratitude for its wonders.

How I reconcile the providence of those gifts with the pointlessness of random misery is too tentative, perhaps too childlike, to survive the scrutiny of abandoned denial. But this much I’m secure about: The power of the 8.2 earthquake that scientists predict for California is indistinguishable from the power that made the night sky’s starry sublime.

MARTY KAPLAN is the Norman Lear professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Reach him at martyk@jewishjournal.com.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.