“I got accepted to the Leipzig University,” Eshchar Gichon, 25, enthusiastically announced at the start of the interview at a Berlin café.

His acceptance into Leipzig University—in this case its veterinary school—is particularly significant for Gichon. It’s part of the closing of a family circle that has just begun.

Leipzig University is the alma mater of Gichon’s great-grandfather, Emanuel Goldberg, who was one of the city’s most prominent professors, a pioneer in the field of optics, photography and information technology as head of the photographic department of the Royal Academy of Graphic Arts and Bookcraft (Leipzig Academy of Fine Arts). But after the war, his legacy was written out of Saxon history, in Leipzig and later in Dresden, where he served as the founding director of Zeiss-Ikon, a leading camera manufacturer under his leadership. Had he stayed, he might have become the “Steve Jobs” or “Bill Gates” of Germany.

“We grew up on stories on him being the director of Zeiss Ikon and all the regular facts about how he was basically a genius,” Gichon said. Gichon moved to Berlin two years ago to study, redeeming benefits of German citizenship due him by virtue of his German lineage. He didn’t expect to be involved in a renaissance of his great-grandfather’s legacy.

Goldberg’s ideas, gadgets, equipment, and inventions were recently on display at “Emanuel Goldberg: The Architect of Knowledge,” an exhibition that opened last March at the Technische Sammlungen Dresden, the site of the former Zeiss-Ikon headquarters. His inventions include a “search engine” (his “statistical machine”–a Google forerunner), and a portable video camera (his “Kinamo”–a FlipCam forerunner).

The process of rediscovery was triggered by Emanuel Goldberg and His Knowledge Machine, a 2006 biography written by Berkeley professor, Michael Buckland.

“It’s hard now to explain how thoroughly Goldberg had disappeared,” Buckland said via e-mail. “From being internationally famous to being almost totally erased outside of Israel. I found doing detective work on Goldberg fascinating in many different ways: he had a most interesting and adventurous life; he did clever things; there is much human interest in his story. Not only was the accepted history of information retrieval seriously incomplete without him, but there was an ethical consideration. He deserved to be remembered, not forgotten.”

Goldberg’s was the classic success-story of a self-made man. Born in Czarist Russia in 1881, Jewish quotas at Russian universities prompted him to leave and study and eventually teach in Leipzig. In 1917, he moved to Dresden, the camera capital of Germany, to eventually found Zeiss Ikon.

In 1933, Nazi stormtroopers marched into the Zeiss Ikon offices armed with pistols and abducted him. Zeiss Ikon negotiated his release and demoted him to the company’s Paris branch. In 1936, the company “bought him out” by having him sign a “non-competition” agreement barring him from competitive activity. His successor was a Nazi, and Zeiss Ikon gradually declined since.

Goldberg rejected an offer to work in the United States alongside Kenneth Mees, the respected founder of the famous Kodak Research Laboratory, to instead move to Palestine in 1937, applying his R&D skills to developing military tools—like compasses and binoculars–to assist the British against the Nazis and later, the Haganah. Goldberg died in Israel in 1970, an Israel Prize Laureate recognized for his contributions in founding ElOp, the optics branch of Elbit, Israel’s publicly traded electronics defense company.

It was only until the 250th anniversary celebrations of Leipzig’s Academy of Fine Arts that Goldberg’s story got retold in the city. As part of a school contest, students were challenged to do research projects on the school’s past professors. Student René Patzwaldt chose Goldberg and contacted his progeny in Israel.

“He did this by sending my grandmother a message on Facebook,” Gichon recalled. “My grandmother had a Facebook account, and he sent a message. We saw the message three months after he sent it. My cousin checked the account and saw the message, and that’s when everything started. We invited him to Israel, he interviewed my grandmother, my grandmother showed him some artifacts of Emanuel Goldberg, and he wrote the project. His project won the competition.”

The Academy of Fine Arts joined forces with Berlin’s Technical University to assemble the exhibition with the Technische Sammlungen Dresden. According to the museum’s director, Roland Schwarz, the exhibition constituted the first time that Zeiss contributed financially to the museum. The exhibition marks a major turning point for Dresden. In 1995, when Buckland first visited the museum for research, the senior staff hadn’t even heard of him.

“If he would’ve continued, we would’ve said the inventor of the computer was Emanuel Goldberg,” said Schwarz from the exhibition grounds.

The exhibition closed in late September, and Schwarz is not sure if it will travel in the near future. Israeli museums he contacted did not express interest. Goldberg’s children (including Gichon’s grandmother, Chava) passed away less than two years before the exhibition opening.

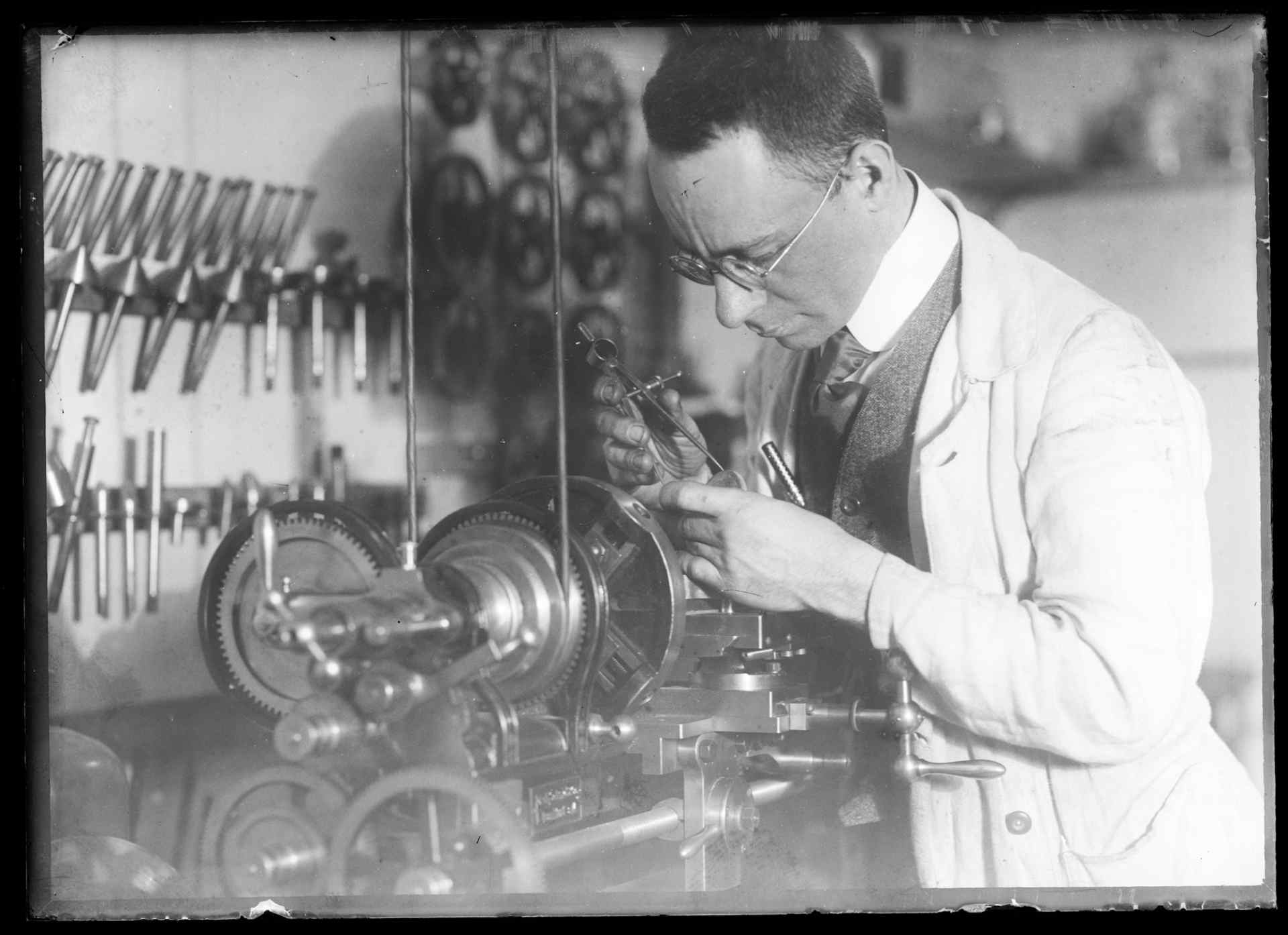

“Luckily, the family decided to transfer the estate of Emanual Goldberg to the museum collection,” Schwarz said. These include his beloved metal lathe that he took to Paris and later to his workshop in Tel Aviv. The 5th floor of the museum will be named after Goldberg, and a section about him will be included in the permanent exhibition.

From the exhibition floor, the house Goldberg designed and built could be seen from the window, near the city’s cable car, and the human story of success and tragedy interests Gichon more than his intellectual achievements. He visited the house on the invitation of its owner and together they are working to install a “stolper steiner” commemorating him.

“We always said, if he would’ve stayed, he probably would’ve been world-famous,” Gichon said. “He would’ve risen high up in the company, and my uncles always said he would’ve won a Nobel Prize.”

This article was originally published in German in the Juedische Rundschau. Orit Arfa is an American-Israeli journalist based in Berlin. Her latest novel, Underskin, is a modern German-Israeli love story whose male protagonist is from Dresden. www.oritarfa.net

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.