Centrism is often no more than a facade. A way of portraying one’s views as more legitimate than the views of others. But centrism can also be real. It can be a practical way for a leader or a politician to cast a net with which to capture as many voters as possible. It can be an ideological belief that the center — avoiding the extremes — is the most commendable way of policy-making.

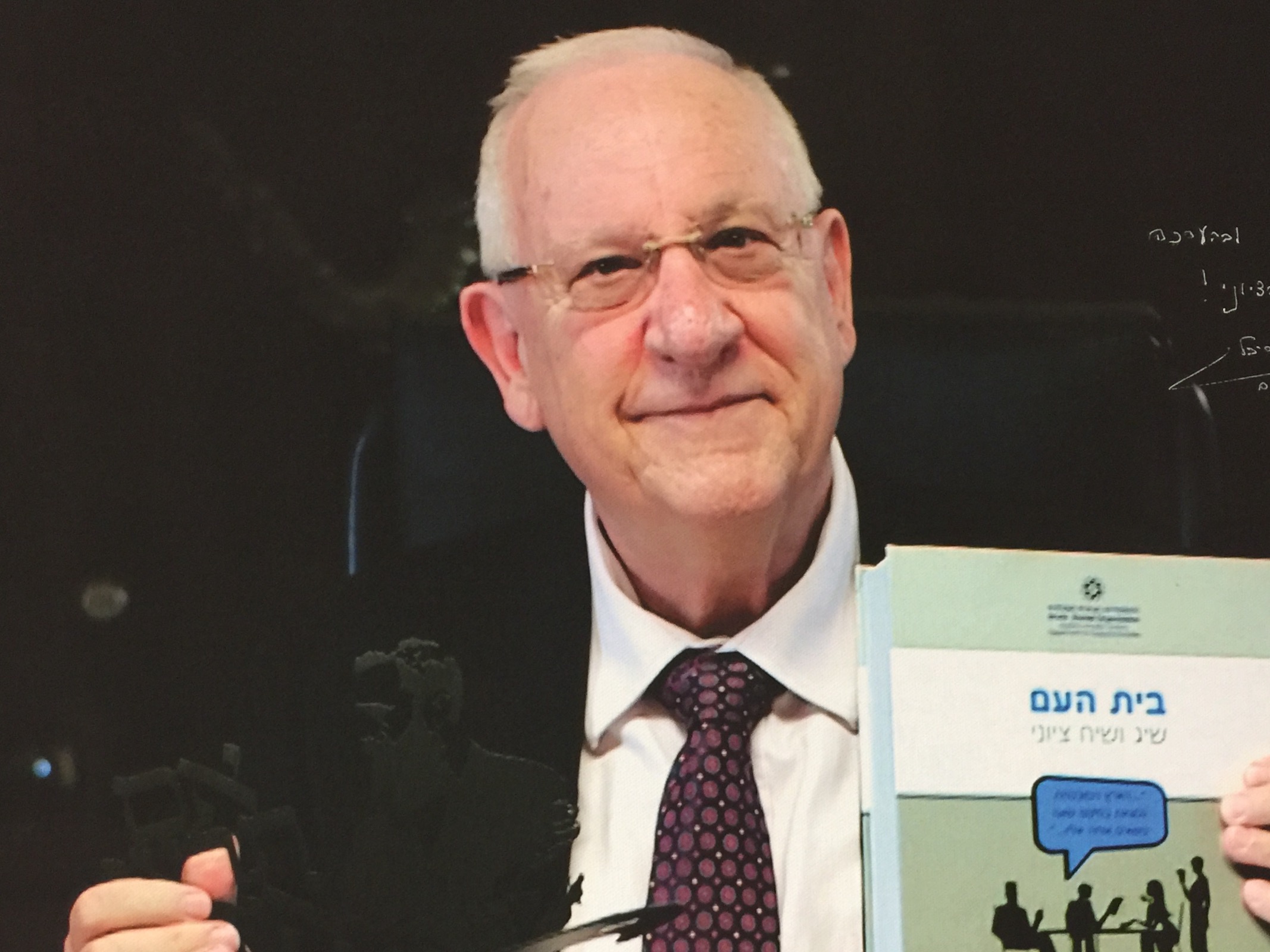

The center is, of course, a moving target, as two Israeli leaders proved in the last couple of weeks. Earlier this week, President Reuven Rivlin exposed himself to a vicious attack from some right-wing quarters by refusing to pardon Elor Azaria, a soldier convicted of manslaughter. His portrait wearing a kaffiyeh — reminiscent of posters preceding the Yitzhak Rabin assassination more than two decades ago — was posted on social media. He was accused of leftism, of weakness.

The center is, of course, a moving target.

Rivlin does not need votes, so there is no conceivable electoral calculation behind his decision. Still, his critics would not grant him the benefit of the doubt. They assume that he does what he does to win the approval of liberal intellectuals, or the media, or the international court of public opinion, or all of the above.

A few days earlier, another Israeli leader disappointed and angered many Israelis belonging to his supposed camp. This time, it was the leader of the left-center Labor Party. He did so by criticizing his camp using a phrase that was made infamous by Benjamin Netanyahu in his first term as prime minister in the 1990s. Netanyahu, back then, whispered in a well-known rabbi’s ears: “The leftists forgot how to be Jewish.” Avi Gabbay, leader of the Labor Party, echoed these words in a somewhat clumsy attempt to hint that Netanyahu had a point — that the left cannot win election in Israel if, rather than owning Judaism, it will run away from it.

Gabbay is not in the same position as Rivlin. He is an up-and-coming leader of a struggling party, attempting to bend it rightward to make it more acceptable to more Israelis, and possibly making it, once again, a real political alternative to the rule of Likud. Gabbay might believe that centrism is better, but he surely sees a practical need to edge toward the center.

In both of these cases, the camp supposedly suspicious of Rivlin and Gabbay was the camp praising their actions. Israel’s opposition hailed Rivlin for being principled and for not surrendering to the right-wing mob. Israel’s coalition hailed Gabbay for finally admitting the grave deficiency of his own camp. In both cases, this was a misfortune: Rivlin’s message is more relevant to the right, which seems all too wiling to forget and forgive a soldier who defied orders and shot to death an unarmed (but not innocent) man. Gabbay’s message is more relevant to the left, which seems all too willing to forget and forgo Jewish traditions and culture in pursuit of universalist ideologies.

Should we consider these two leaders to be centrists because of their decision to move away from their initial base of support and toward an imaginary (or maybe real) center? Or maybe these leaders are radicals, who boldly defy convention and a base of support, to follow a path they believe is the right path.

The answer in this case is both. That is to say: In today’s world, being a centrist is often more radical than all other options. Netanyahu does nothing radical when he plays to his base of support and gives his voters what they want. The leaders of a leftist party such as Meretz do nothing radical when they also play to their base of support and drag them away from the Israeli consensus and into the land of political impotence. Rivlin and Gabbay try something bolder — to see if by being centrists they can also nudge their audiences toward centrism, moderation and relevance.

Whether they chose the topic or the right phrase to make their case is a good question. The reaction to their respective decisions was hardly encouraging, and hence I am not certain the answer to this question is positive. But the sentiment is commendable. Yes, Israel should not be a place where soldiers shoot unarmed terrorists without proper cause and where the mob supportive of them makes the rules. Yes, Israel should not be a place where opposition to the government means abandonment of Jewish traditions and culture. Radical centrism is needed.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.