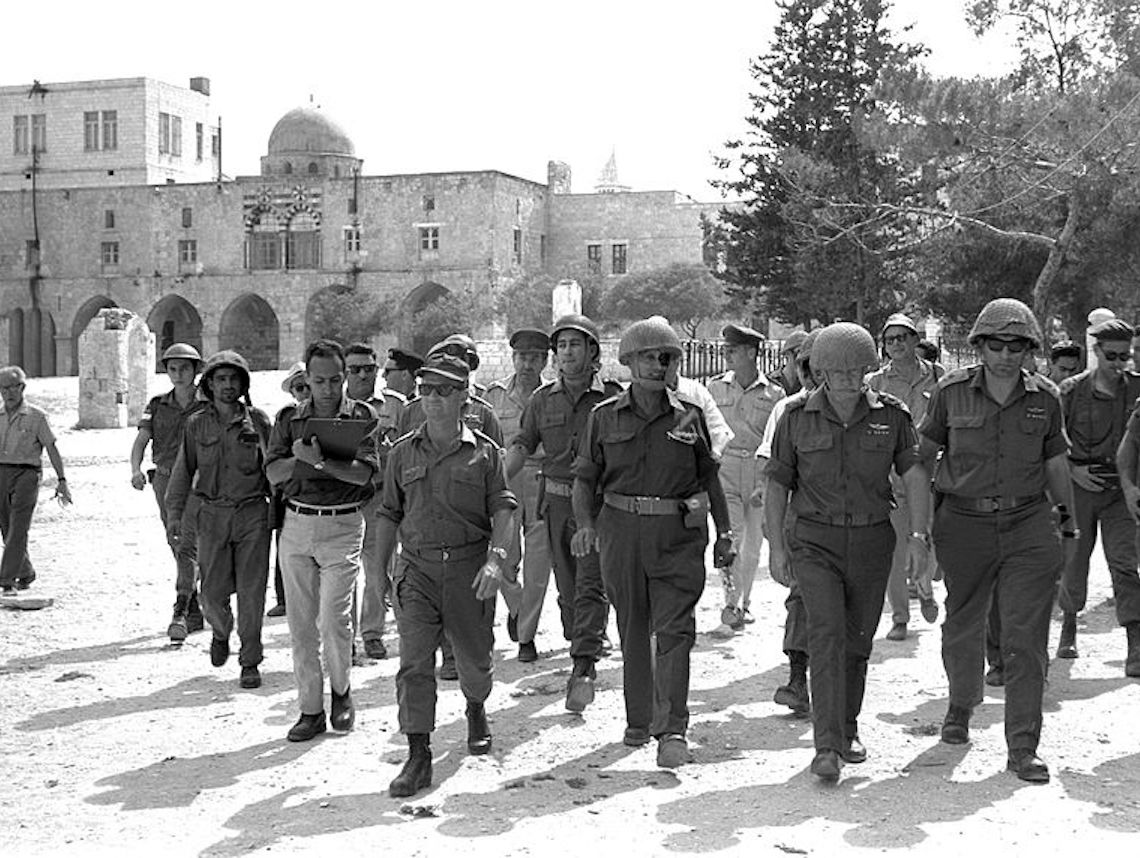

Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, Chief of staff Yitzhak Rabin, Gen. Rehavam Zeevi (R) And Gen. Narkis in the old city of Jerusalem. Photo from Wikipedia

Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, Chief of staff Yitzhak Rabin, Gen. Rehavam Zeevi (R) And Gen. Narkis in the old city of Jerusalem. Photo from Wikipedia Israel’s State Archives has unsealed documents from the Six-Day War after 50 years. They include transcripts of full cabinet meetings and of the Security Cabinet meetings. Here are a few observations.

In Cabinet meetings, people say many things. In tense Cabinet meetings, they say even more things. Thus, when transcripts are released, it is easy to isolate quotes and make big headlines out of them to serve a position or an ideology. If it were up to us, a politician muses, we would “deport the Arabs to Brazil.” Is this a statement that proves Israel’s malicious intentions? Some might say yes. They had the same reaction when Yitzhak Rabin mused about his desire to see Gaza drowned in the Mediterranean.

But you also can see it as a statement proving the sobriety and realism of Israel’s ministers at the time — a statement proving that they realized, on Day One, that occupying a territory in which many Arabs reside is going to be a headache. They did not deport anyone to Brazil. They were stuck with the headache. We still are stuck with it.

Not everything the ministers said seems impressive in retrospect. But what is quite impressive is the ministers’ refusal to engage in desperation in the weeks leading to the war and their reluctance to surrender to euphoria after it. The ministers behave in these meetings as all Israelis did: The period leading to the war was highly worrisome and the country was in a dark mood during the three weeks of “waiting.” The period after the war was one of celebration and invincibility.

The ministers are apprehensive, and they are uplifted — but in a more subdued way. They do not panic before; they do not lose proportion after. Yes, many of their assessments seem naive, misconstrued, even foolish in retrospect. But this is not due to a lack of seriousness.

Reading the debate about the future of the West Bank feels prescient. There are annexationists who want to absorb the territory and believe the demographic challenge of absorbing so many Arabs along with the territory will sort out itself. Menachem Begin, a member of the emergency Cabinet that was assembled prior to the war, argues that within seven years there will be a Jewish majority in the West Bank. There are those for whom demography is the key. Pinchas Sapir, the finance minister, worries about Israel’s future as a Jewish state if so many Arabs will become residents or citizens of Israel.

It is almost boringly familiar, and yet so distant.

I’m reading a transcript of a Security Cabinet meeting from May 26, 1967. Rabin, then the chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), is asked to assess whether Israel can withstand an attack. Look how careful he is: “I think if we have the tactical surprise, there is a possibility … that we will have achievements.”

Here is a question: Was this a rhetorical failure on part of the IDF and Rabin? Consider an alternative scenario: It is the same meeting, but Rabin promises a great victory, then Israel faces a military defeat. What would we say in such a case? Probably that the chief of staff didn’t assess the situation correctly and thus provided Israel’s political leaders with inaccurate information on which they made the wrong decisions.

But no one has the time or reason to ask the exact same question when the assessment of the military commander is inaccurate in a positive sense — that is, a prediction of great difficulty that later proves to be an overstatement.

And there is more. A minister warning defense minister Moshe Dayan that the IDF ought to be reminded to treat the civilian population humanely. Ministers arguing for and against taking East Jerusalem. Concern that overeagerness could prolong the war and occupy more territory because of the victories.

There also are lies that Israel decides to tell. The protocol shows how Israel attacked Syria in the Golan Heights. Minister Yigal Alon calls for the attack, disregarding the possibility of diplomatic tension with Russia because of it. He says he prefers controlling the Heights over diplomatic problems with the Russians.

The director of the Foreign Ministry warns against action — attacking Syria will complicate things for us with the Russians, he argues. But Rabin wants action. “Ending such a war without hitting the Syrians would be a shame,” he says.

Israel tells the world that the Syrians are fighting. “This is not the truth,” argues minister Haim-Moshe Shapira. True, says Alon. “I admit that this isn’t the truth, but these are the kind of lies that we can tell to have peace” — namely, to have the Syrians’ cannons removed from the Heights that overlook Israel.

Some things still feel different, and the most notable of them is the approach of the representatives of Israel’s religious-Zionist sector. Today, they are the most hawkish. In 1967, they famously were the least hawkish. They were the ones preaching for caution and moderation.

Shapira did not want the attack on the Syrians. His friend Zerach Warhaftig cools down Dayan when the defense minister suggests that Israel send its forces to Beirut.

“I would argue that we should have some limits,” Warhaftig says.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.