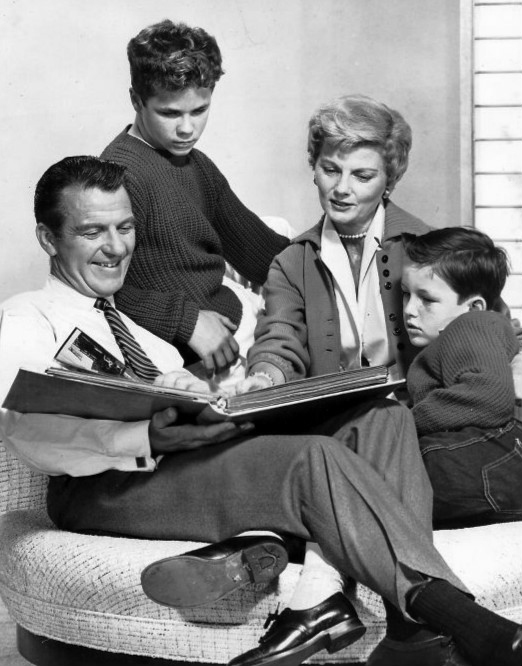

Like many women who grew up with ’50s-era fathers, I had a complicated relationship with mine.

On the one hand: complete adoration. I was most certainly a Daddy’s girl, to the point where I even had to eat whatever he was eating (I did draw a line at kishkes). On the other hand: He was no doubt a bit controlling.

As a result, my 20s were one huge rebellion against him. Not against men in general, but against this one man and my need to figure out who I was, separate from him.

After I got past that, though, I began to truly appreciate him as an authority figure. If I wanted the uncoddled truth about a situation, I would wait till my father came home.

Plenty of mothers can, of course, play that role, and as a mother, I’ve tried to blend the best of both of my parents. But raising a son in a climate where masculinity is under siege — not uncivilized masculinity, but masculinity itself — has made me think a lot about the subject.

My 8-year-old would fall into the very unpolitically correct category of “boy’s boy.” Empathy is situational, and aggression needed to be tamed. But he came out of the womb with a desire to rule every environment he’s ever been put in. I used to apologize for his bossiness until one father said to me, “Why are you apologizing? If we’re lucky, he’ll eventually use these skills to improve the world.”

Four years later, I saw the first step in this process. In the fall, Alexander learned how to create origami. The other kids in his third-grade class were so fascinated by it that he began to give them lessons. Then he formed an origami studio. The studio made so many origami sculptures that he asked the teacher if students could sell them, with the money going to a charity. A month later, the studio set up an origami table at the school’s fair. With entrepreneurial skills that seemed to come out of nowhere, he sold $136 worth of origami, with proceeds going to the local food pantry.

For me, the best part were the days leading up to the fair and the days that followed. He had become a more mature, confident Alexander — the best Alexander I had ever seen. It wasn’t just the responsibility, it was the ownership of a project: He became less bossy and more of a leader.

He happened to have a teacher this year who nurtured this evolution. But in general, the New York City public schools — following trends — are failing our boys. The Department of Education cut gym class to once a week so that the kids are a lot more inactive. In my experience, many of the female teachers are especially mean to the boys — even to the boys who act like angels. There seems to be an assumption of male guilt.

I didn’t fully understand this until I read a recent op-ed in The Washington Post called “Why can’t we hate men?” Written by a professor of sociology at Northeastern University, the piece contained phrases like “the land of legislatively legitimated toxic masculinity” and told men: “Don’t run for office. Don’t be in charge of anything. Step away from power.”

The best of masculinity should be cherished; the worst of it, civilized. That indeed would be progress.

For genderists, fixing “the problem of masculinity” means emasculating men. The fact that they don’t see how counterproductive this is — do happy, confident men rape and abuse? I don’t think so — is beyond mystifying.

“Fixing” masculinity first means trying to understand it. And as we well know, blind hatred never leads to understanding. Fortunately, the sports programs in New York City have yet to be infected, and they’ve been encouraging a healthier masculinity (as well as a healthier femininity). Strive for excellence, respect, good sportsmanship. Play hard — but within boundaries.

My dad, now 88, who taught Alexander how to build with empty boxes, is now capable of only superficial engagement. But if Alexander is in any sports competition, my dad never fails to ask, “Did he win?”

I imagine some mothers, steeped in cultural Marxism, may take offense to that question. But for me, it ties my father to my son. Moreover, striving to succeed, to “dominate,” isn’t inherently bad. It’s what moves the world forward.

The best of masculinity should be cherished; the worst of it, civilized. That indeed would be progress.

Happy Father’s Day, dad.

Karen Lehrman Bloch is an author and cultural critic.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.