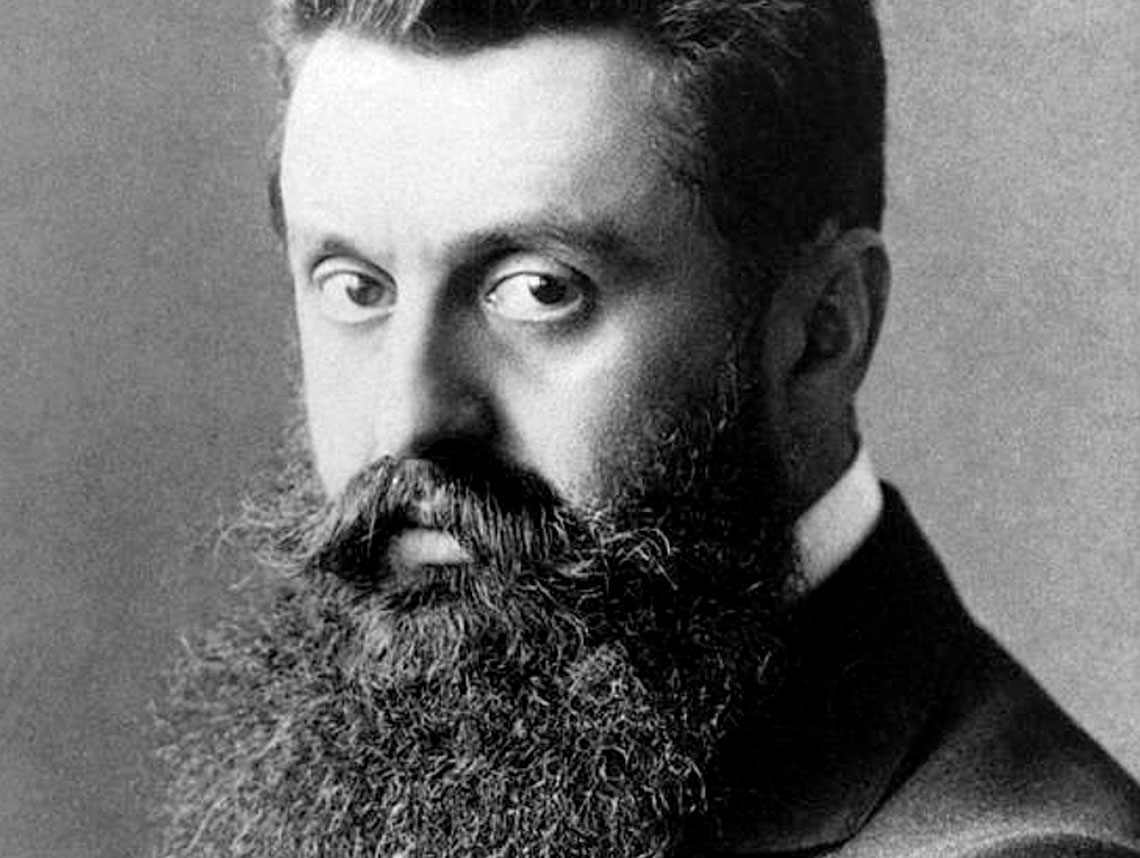

One hundred and twenty years ago, on Sept. 3, 1897, a Viennese journalist named Theodor Herzl wrote in his diary: “In Basel I founded the Jewish state.” He then added a curious note: “If I were to say this out loud today, everybody would laugh at me. In five years, perhaps, but certainly in fifty, everybody will agree.”

This was two days after he returned from Basel, Switzerland, where, against all odds, he managed to put together the First Zionist Congress — the event that symbolizes the Jewish claim to self-determination.

Herzl had good reasons to feel elated about Basel: 208 delegates from 17 countries, the elite of European press, all dressed in solemn tuxedos, packed Basel’s casino to discuss his proposed solution to the “Jewish Problem.”

For three days, delegates listened to fiery speeches, debated and finally came up with as clear a definition of Zionism as one can possibly articulate: “Zionism seeks to establish for the Jewish people a publically recognized, legally secured homeland in Palestine.”

Sure enough, upon returning to his office at the Neue Freie Presse newspaper in Vienna, Herzl’s co-workers greeted him with obvious mockery, as the “future head of state.” But that was the least of the problems Herzl had to face; skepticism, sarcasm and opposition loomed all over the world. The Vatican issued a letter protesting the “projected occupation of the Holy Places by the Jews.” (Sound familiar?)

The Ottoman authorities had their suspicions aroused and began to restrict the manner in which Jews were acquiring land in Palestine, especially near Jerusalem.

But the worst opposition came from fellow Jews. Orthodox rabbis condemned Herzl’s attempt to hasten God’s plan of redemption, while Reform rabbis saw it as interference with their vision of becoming a moral light unto the nations by mingling among those nations.

Baron Edmond de Rothschild, the French philanthropist who supported Jewish agricultural communities in Palestine since the 1880s, was adamantly against efforts to obtain international legitimization of Jewish national claims. He feared (justifiably) that such efforts would lead to tougher Ottoman restrictions, and that Jews like him would be subject to charges of dual loyalty.

Ahad Ha’am, the most influential Jewish intellectual of the time, wrote about his time in Basel that he felt “like a mourner at a wedding feast.” His motto was, “Israel will not be redeemed by diplomats, but by prophets.” He could not forgive Herzl for luring the world jury with false hopes of a diplomatic solution.

But the cleavage between Herzl and Ahad Ha’am was much deeper. Ahad Ha’am claimed it is futile and possibly harmful to argue the Jewish case in diplomatic courts when the Jewish people are spiritually unprepared for the task. What must be done first, he wrote, is “to liberate our people from its inner slavery, from the meekness of the spirit that assimilation has brought upon us.”

Herzl, on the other hand, understood that the very act of bringing the Jewish question to the international arena, regardless of its outcome, would change the cultural ills of the Jewish masses and rally them to the cause.

In retrospect, he was right. There were several forerunners of Jewish self-determination (for example, Moses Hess, Yehuda Alkalai, Leon Pinsker, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda and Ahad Ha’am himself), but their writings were directed inward, toward the intellectual cliques in the Jewish shtetl; their overall impact was therefore meager.

Bringing the Jewish claim to an international court created the cultural transformation that Ahad Ha’am yearned for — the shtetl Jew began to take his own problem seriously and the Zionist program became one of his viable options.

History books make a special point of noting that Herzl’s predictions were miraculously accurate. Israel was declared a state on May 14, 1948, 50 years and eight months after Herzl wrote: “In Basel I founded the Jewish state.”

However, I believe Herzl in effect founded the Jewish state much earlier. True, Herzl’s specific plan to persuade the Ottoman sultan to allocate land for a Jewish state was sheer lunacy and led to painful disappointments. But transforming Jewish statehood into an item on the international political agenda was a monumental achievement — it maintains this position today.

Moreover, the idea that Jews are reclaiming sovereignty by right, not for favor, completely changed the way Jews began to view their standing in the cosmos. It transformed the Jew from an object of history to a shaper of history.

This new self-image was the engine that propelled history toward a Jewish statehood already in the early 1900s. The 40,000 Jews who made up the Second Aliyah (1904-1914) were different in spirit and determination from the 35,000 Jews who came earlier with the First Aliyah (1882-1903). At their core, they knew they were building a model sovereign nation and that Zionism is the most just and noble endeavor in human history. They established kibbutzim, formed self-defense organizations, founded the town of Tel Aviv and turned Hebrew into a practical spoken language. This spirit of hope, purpose and immediacy emanated from the Basel Congress, not from the utopian “in time to come” Zionism of Ahad Ha’am.

The diplomatic efforts that led to the Balfour Declaration and the subsequent ideological immigration of the Third Aliyah (1919-1923) all were direct products of the Zionist movement and made statehood practically inevitable.

The miracle of Israel was planted indeed in 1897.

If I had to choose the single most significant impact that the Basel Congress has had on our lives here, in 2017 Los Angeles, I would name one forgotten statement that Herzl made in his first speech at the Basel Congress. On the morning of Aug. 29, 1897, after 15 minutes of wild cheering, Herzl took the stage and said, “Zionism is a homecoming to the Jewish fold even before it becomes a homecoming to the Jewish land.”

As I observe how the miracle of Israel is becoming the most powerful uniting force among our divided communities, and as I witness the excitement of our children, grandchildren and college students as they internalize the relevance of Israel to their identity as Jews, Herzl’s statement about “homecoming to the Jewish fold“ stands out perhaps as more visionary than his prediction about Israeli statehood. It was the future of the Jewish people, not just of Israel, that was forged there in Basel, 120 years ago.

JUDEA PEARL is Chancellor’s Professor of Computer Science and Statistics at UCLA and president of the Daniel Pearl Foundation.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.