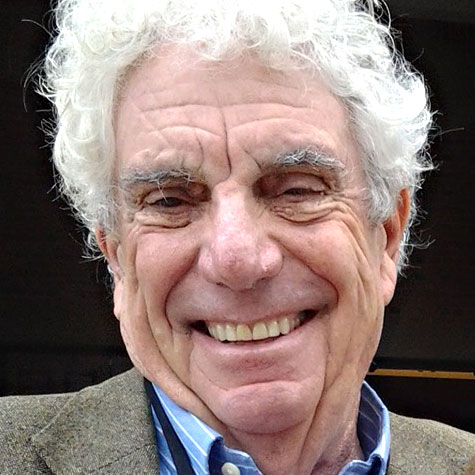

When Rabbi Harold M. Schulweis was the eloquent young rabbi of Temple Beth Abraham in Oakland, he gave many uncompromising sermons against the social and economic injustices that afflicted the community.

The sermons impressed my mother, who was principal of the religious school. She knew it took courage to speak so forthrightly from the pulpit of a temple run by conservative businessmen, some of them in the slum apartment or pawnshop businesses, both of which profited from Oakland’s large number of poor African Americans. Having been a schoolteacher in Oakland’s tough neighborhoods, she had a firm but understanding opinion of the city’s social and economic ills and agreed completely with Schulweis’ view of economic exploitation.

So it meant a lot to her that this rabbi with guts officiated at the event that won him a place in the Boyarsky family history, the wedding on July 21, 1956, of Nancy Belling and Bill Boyarsky. It meant something to me, too. Schulweis exemplified the social activist rabbi emerging through the complacency of the silent ’50s.

Recently, I visited Schulweis, now the distinguished rabbi of Valley Beth Shalom in the San Fernando Valley. A couple of weeks earlier had spoken to young Jewish leaders gathered together to discuss participation in Los Angeles civic life, and the conversation had started me thinking. We had covered politics thoroughly. But as the conversation moved along, I was surprised to find the group was just as intent — maybe even more so — in pursuing another subject: their quest for a more spiritual life.

Afterward, I wondered how this exploration of spirituality squared with the fierce determination of the civil rights-era rabbis to be part of the tumultuous world?

Schulweis said the two cannot be separated. The values of Judaism, he said, are intertwined with public values. He referred me to the work of his teacher, the late Abraham Joshua Heschel, professor of Jewish ethics and mysticism at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America.

Heschel was with Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1965 civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala. This is how Heschel described the event: "For many of us, the march from Selma to Montgomery was both protest and prayer. Legs are not lips, and walking is not kneeling. And yet our legs uttered songs. Even without words, our march was worship. I felt my legs were praying."

Schulweis’ social activism is also deeply rooted in Jewish tradition. And that is why, he said, Jews have listened to him — often uncomfortably — in Oakland, in the Valley and around the country.

"They do not want to be preached to without an argument that is based on Jewish thinking, Jewish experience, Jewish life," he said. "Otherwise, they might as well be reading an article in The New York Times."

A memorable example of what Schulweis meant was his Rosh Hashana sermon in 1992 on Judaism and homosexuality.

He began with the verse from Leviticus beloved by the anti-gay crowd: "Do not lie with a male as one lies with a woman. It is an abomination."

He recalled how a mother of a young gay man visited him and told how her son had committed suicide. "’I’m here to ask you rabbi, was my son an abomination? Was he punished? Is that why he died?’"

"Her question never left me," Schulweis said. "It is one thing to read a scientific paper or to examine a rabbinic text; it is another to look into the pained eyes of another human being."

He conceded "there are rabbis as knowledgeable and as moral as I who maintain the law is the law, that the biblical verses of Leviticus cannot, must not, dare not be changed…. Were I to follow their judgment, I would, in the last analysis, be compelled to say to those sons and daughters who seek Jewish wisdom and equity, ‘Abstain forever…. ‘"

"I confess, I cannot for the life of me look into their eyes and deny them the intimacy, love, pleasure and sensuality that is God’s gift," the rabbi said. "I cannot in God’s name, in the name of Torah and Israel, speak in that fashion. Because such a verdict runs against my Jewish sensibility."

"To bring misery, pain, torture, anguish to innocent people who are created the way they are violates my Jewish conscience," he continued. "I cannot bury my Jewish sense of fairness and compassion. Sexual orientation is no curse unless we assign it to our human malediction … it is not God who punishes; it is human society that punishes, humiliates, shames and excommunicates."

Schulweis’ conversation with the grieving mother affirmed what he long knew. The synagogue is not a refuge from the world. Young people, such as those I talked to, will realize that the quest for spirituality cannot be divorced from the streets around them.

As Schulweis said in the beginning of his sermon: "Judaism is wedded to creation. We are in this world and of this world and not of another. Judaism promises no escape from the sand and rocks of reality, and its idea of salvation counsels no flight to another world."

Bill Boyarsky’s column on Jews and civic life appears on the first Friday of

each month. Until leaving the Los Angeles Times in 2001, Boyarsky worked as a

political correspondent, a metro columnist for nine years and as city editor for

three years. You can reach him at bw.boyarsky@verizon.net.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.