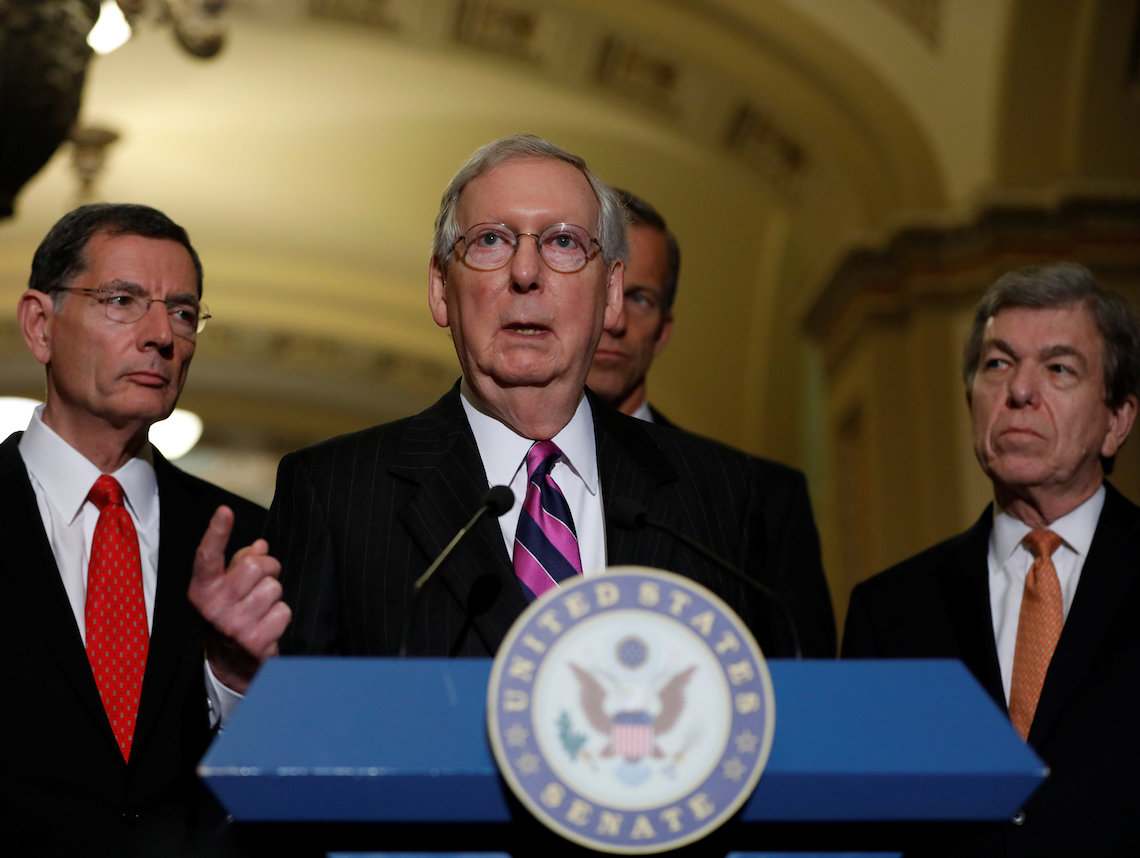

Sen. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, accompanied by Sen. John Barrasso (R-Wy.) and Sen. John Thune (R-SD) and Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), speaks with reporters following the party luncheons on Capitol Hill on Aug. 1. Photo by Aaron P. Bernstein/Reuters

Sen. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, accompanied by Sen. John Barrasso (R-Wy.) and Sen. John Thune (R-SD) and Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), speaks with reporters following the party luncheons on Capitol Hill on Aug. 1. Photo by Aaron P. Bernstein/Reuters Moses received Torah at Sinai. He transmitted it to Joshua, and Joshua to the elders, and the elders to the Prophets, and the Prophets to the Men of the Great Assembly. They said: raise up many disciples, be deliberate in judgment, and build a fence around the Torah.

— Mishnah Avot 1:1

It is procedure that marks much of the difference between rule by law and rule by fiat.

— Wisconsin v. Constantineau (1971)

Process is boring, but it also is crucial, as the Supreme Court observed. And it is particularly crucial for Jews as we consider the Republican effort to repeal Obamacare.

This is a live issue. Despite July’s failure of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s plans, Republicans have made clear that they will continue to pursue repeal. And both his and House Speaker Paul Ryan’s abuse of Congressional process show that they are adept at rule by fiat.

To be clear: I believe the repeal plans are a moral abomination. But apart from substance, let’s look at the procedure. The GOP’s Obamacare repeal process mocks democracy. Health care approaches one-fifth of the entire U.S. economy, yet the process was conducted in near total secrecy. On the House side, the bill was written behind closed doors without any input from the Democrats. Ryan rushed it to the floor before the Congressional Budget Office could even determine what its effects would be. If enacted, the American Health Care Act would strip 23 million people of coverage, but the process was designed precisely so that Congressmembers would be kept in the dark.

McConnell’s process was even more secretive; the Senate bill was cooked up in his office with no input from patients, health experts, advocacy groups — or even most of the Republican caucus. The March of Dimes paid for McConnell’s polio treatment as a child; he refused even to meet with the organization. His last-ditch attempt — the so-called “skinny” repeal — was introduced five hours before it was supposed to be voted on, with no hearings or public input whatsoever. GOP senators have announced yet another plan to rush through a health package with the same high-handed secrecy.

All legislation resembles sausage-making, but this was fetid even for a slaughterhouse. Julie Rovner, who has covered this issue since the 1980s wrote, “The extreme secrecy is a situation without precedent. … I have been here for 30 years and never seen anything like this.” Journalist Ezra Klein noted that “Republicans are making life-or-death policy for millions of Americans with less care, consideration and planning than most households put into purchasing a dishwasher.” John Podhoretz, no liberal, tweeted, “I have never seen such unanimity in the horror everyone on all sides is expressing toward the Senate process on this health care bill.” (Spare me references to the creation of Obamacare, which took 14 months, included literally hundreds of GOP amendments, dozens of hearings and extended bipartisan negotiations.)

But why is it a Jewish issue? Let’s consider the epigraph from Pirkei Avot. This Mishnah is perhaps Judaism’s most foundational text, and it links the chain of rabbinic authority to three central moral injunctions, particularly “be deliberate in judgment.”

Most classical commentaries, from Rambam to the Chasidic masters, do little with this passage. They gloss it as simply “do not move too fast” or “be careful.” This might be useful, but it really misses the point. Telling us to “be deliberate in judgment” requires us to consider the deeper question of how we do that: What conditions will make us deliberate? Unsurprisingly, much of Avot concerns the proper behavior of public decision-makers: It warns how the wielders of state power betray those who trust them (Avot 2:3).

Being serious about deliberation in judgment means we must establish institutional practices that make us deliberate. Both character and structure matter. This reflects virtually all Jewish spirituality: Our tradition creates practices to bring the soul closer to God. Commanding us to remember God is not good enough. We do it by practices such as uttering blessings, wrapping tefillin, observing Shabbat, etc.

In other words, Avot 1:1 is the “Jewish Due Process” clause. It holds that if anyone makes crucial decisions about people, they must follow proper procedure. Only then can they truly be “deliberate in judgment.” Like long-settled judicial principles of “due process,” “deliberation in judgment” requires that those affected by state power have a right to be heard, to contest those whose interests are adverse, to have transparent and open government, to have decisions made on the basis of evidence and rational judgment rather than arbitrary caprice. If leaders make decisions without hearing from those affected and subjecting their own thoughts to scrutiny, they are not really deliberating at all. Such “process” is not judgment. At best, it is no more than a series of irritable mental gestures; at worst, tyranny with window dressing.

When Congress holds literally tens of millions of lives in its hands, to refuse to listen to those who will suffer mocks the Torah’s requirement of deliberation in judgment. McConnell and Ryan do not care. Do we?

JONATHAN ZASLOFF is professor of law at UCLA, where he teaches, among other things, property, international law and Pirkei Avot. He also is a rabbinical ordination candidate at the Alliance for Jewish Renewal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.