James Coley and Robert Warfield, case workers for the Integrated Recovery Network, walked into the Twin Towers Correctional Facility with purpose and confidence, exactly the qualities needed for talking to some of the approximately 2,500 mentally ill inmates confined in the downtown Los Angeles jail.

They were seeking homeless men who, nearing completion of their sentences, would benefit from a unique recovery program that helps provide access to housing, medical care, counseling and jobs for such inmates. I tagged along, overwhelmed at times by the sights and sounds of the grim penal facility near downtown Los Angeles that Sheriff Lee Baca calls America’s largest mental hospital.

A jail as a mental hospital? That’s the sad state we’re in, with thousands of homeless arrested and jailed in the Twin Towers, which provides minimal psychiatric and addiction rehabilitation, then sent back to the streets to sicken or die, or to be arrested again for another minor crime. In fact, according to Marsha Temple, executive director and founder of the Integrated Recovery Network (who is married to KCRW’s political talk-show host Warren Olney), most of the mentally ill homeless are crime victims themselves, preyed upon by robbers, drug dealers, perverts or the vicious individuals who find sport in assaulting them.

There are few places for these potential victims to go unless they are arrested. Since California’s mental hospitals were closed down after passage of the ill-fated 1967 Lanterman-Petris-Short reform law, the state’s government has built few of the community treatment centers that were supposed to replace them. In any case, state law makes involuntary commitment extremely difficult — even if there were a place to send the mentally ill.

The failing system also affects those mentally ill fortunate enough to have homes and families. They go without care unless they agree to it. And most often, only the affluent can afford the level of continuing mental treatment needed for sick relatives, because insurance coverage is commonly so minimal. Most mentally ill live in unending limbo, receiving sporadic help at best.

Two recent murder cases point up this situation. One involves Michael Rodney Kane, an elementary school teacher charged with stabbing his estranged wife, Michelle Ann Kane, to death on a San Fernando Valley street on June 15. All the circumstances of the case have not yet come out, but newspaper accounts say he had been hospitalized, according to his deceased wife, for suicidal thoughts and stress and was also a heroin and methamphetamine addict.

The other case involves John Zawahri, who shot and killed five people and wounded others in Santa Monica on June 7 before being gunned down by police. When Zawahri was in high school, a teacher spotted him looking for assault weapons on the Internet and turned him in to the principal. Zawahri ended up in the UCLA psychiatric ward but was released.

The Integrated Recovery Network focuses on homeless inmates receptive to being helped. Executive director Temple, an attorney, has built a system that features recovery programs tailored to the needs of each inmate, rather than the one-size-fits-all methods of many other rehabilitation programs. “It is very individualized. That is the secret of our success,” she said. The first priority is finding housing for the inmate after he or she is released, either in a home, apartment or group facility, with the rent paid for through government and other aid programs. Then ex-inmates are steered into treatment for addiction as well as mental illness. Of the first-time offenders in the program, only about 20 percent commit another crime. For veteran criminals, that figure rises to 50 percent to 60 percent, Temple said, but that is still below Los Angeles County’s recidivism rate of 70 percent.

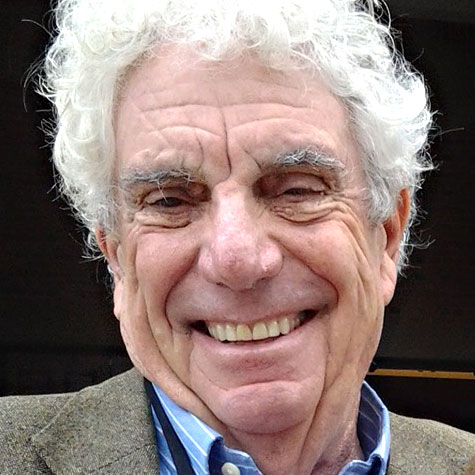

Marsha Temple, executive director and founder of the Integrated Recovery Network, which works with mentally ill inmates.

Marsha Temple, executive director and founder of the Integrated Recovery Network, which works with mentally ill inmates.

I found it enlightening to watch Recovery Network caseworkers Coley and Warfield, both 30 years old, as they interviewed inmates in the Twin Towers on the afternoon of June 13. I was impressed by the way they talked to the inmates we saw during the day. Coley and Warfield were neither too tough nor overly sympathetic but spoke directly in a straight-on manner that was both supportive and respectful.

We went into the nine and 10 side-by-side buildings. The cellblocks were crowded, with cots in day rooms designed to give the inmates some open space. With the cots packed together, these mentally ill men are forced into constant close contact with one another.

The case workers asked to see one Recovery Network client who was back in jail on what seemed to me to be trumped-up, or at least improbable, charges of stealing a Pepsi from a convenience store. He suffered from bipolar and post-traumatic stress disorders, the latter the result of his time in state prison more than a decade ago on a robbery charge. He was African-American. The overwhelming majority of the inmates are African-American or Latino.

A marijuana possession charge had originally sent the man to the Twin Towers, years after his state prison time. One day, Coley, on his rounds through the jail, asked, as he always does, if anyone needed help with housing. The inmate said he did. “James told me to write a short essay with five long-term goals and five short-term goals” and describe what triggered his lawbreaking, he told me. “We came up with a plan.”

By completing the essay, he helped convince caseworkers Coley and Warfield that he would be a good candidate for housing and treatment. Upon release, the man moved into housing found by the Recovery Network, enrolled in a political science class at Trade Tech, and then “I ran out of gas,” he said. Walking home from the store with two bags of groceries he had purchased, he stopped at a convenience store and bought a Pepsi. The security guard accused him of stealing it. The man denied it, and slugged the guard.

Back in jail and facing a possible third-strike charge, which could land him with a lifetime sentence, he found that caseworkers Coley and Warfield hadn’t abandoned him. His public defender is overworked and hasn’t pushed his case. But Coley visits him and tries “to get on top of the lawyer.” The inmate said, “The Integrated Recovery Network hasn’t given up on me. It makes you feel they are in for the long haul.” Or, as Coley told me afterward, “If they fall down, we don’t shun them.”

Coley and Warfield stopped by another cellblock. There was something that bothered Coley and Warfield about one inmate who asked to speak to them. He said he had been jailed for jaywalking, which the caseworkers felt was unlikely. And he had teardrops tattooed under an eye, a tipoff to gang membership. To Coley and Warfield, it is important that their prospects be honest with them, and this man didn’t seem to meet that standard. But they asked him to write an essay, and they said that if he had done so when they returned the following week, they’d talk to him more.

Another man, who said he was in for possession and sales of drugs, seemed a better prospect. He said he suffered from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and stress. He wanted out of his old life — and to enter a drug program.

We walked through other parts of the jail. On the seventh floor of one of the towers, the severely mentally ill were under heavy control, handcuffed when they were taken from one place to another, restricted to one-man cells, with doors locked 20 hours a day. Guards check the cells every 15 minutes. In another area, reserved for even more destructive inmates, the prisoners wore special mesh clothing they could not rip off. I heard screaming and banging on the doors. Some inmates, drugged, were curled up on their cots or in a corner of their small cells. Some of the cell doors had red signs warning that the inmates were potentially violent. Inmates on this floor are too dangerous and sick for the Integrated Recovery Network to help.

Over the years, I’ve watched the state’s mental health care system deteriorate to this — a jail as a mental hospital. As a young reporter in Sacramento, I visited state hospitals where the mentally ill and disabled were warehoused and forgotten except by relatives who often had to make long drives to distant locations. I thought it was good idea to replace those with community centers closer to home. Then I watched as those centers were never built, the victims of budget-cutting and misplaced priorities by Gov. Ronald Reagan and his successors. Finally, with the hospitals closed, I saw the mentally ill take to the streets, where we see so many of them today.

As James Coley and Robert Warfield make their rounds in the Twin Towers, they and others like them are trying to pick up the pieces of this shattered system.

Bill Boyarsky is a columnist for the Jewish Journal, Truthdig and L.A. Observed, and the author of “Inventing L.A.: The Chandlers and Their Times” (Angel City Press).

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.