Survivors of Mauthausen beg for food through a barbed wire fence. Photos by U.S. Army photographer Ken Parker

Survivors of Mauthausen beg for food through a barbed wire fence. Photos by U.S. Army photographer Ken Parker The 13 black-and-white pictures sat in a cardboard box in a North Hollywood residence, half a world and seven decades removed from the horrors they captured.

In August, Robert Aguilar, 78, a retired truck driver, found the photos at the back of a cupboard as he and his wife, Paula Parker, 69, prepared to sell their townhouse and move to Nevada to live out their retirement. The pictures are presumed to have been taken by Parker’s father, Ken Parker, a U.S. Army photographer in World War II.

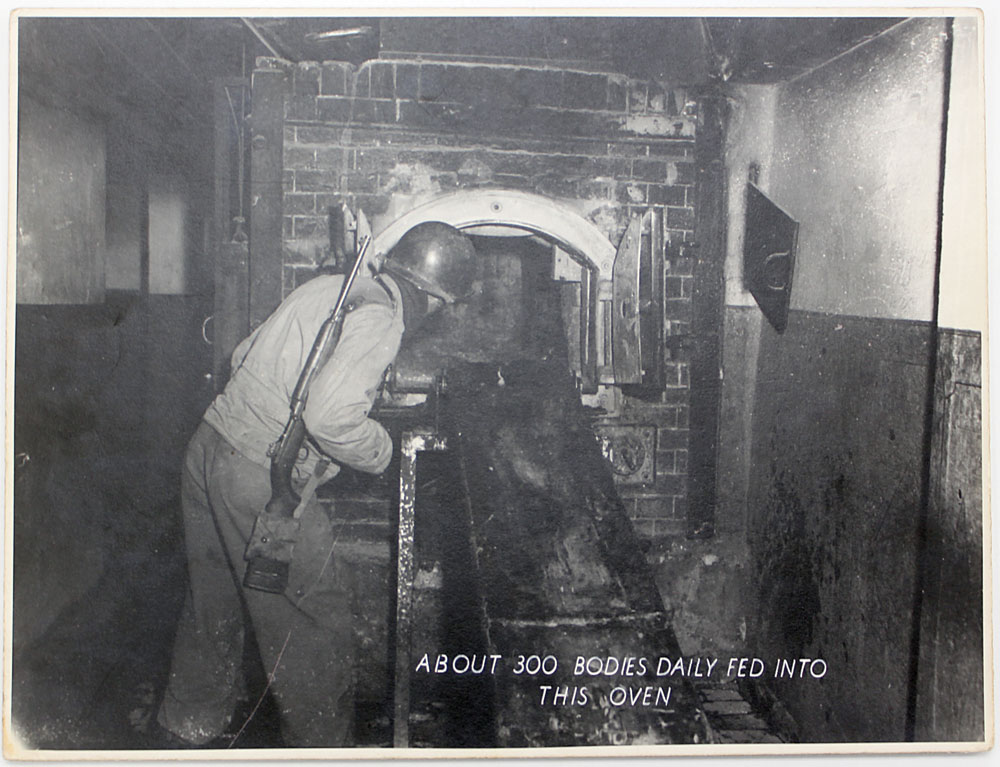

Found jumbled together with an Army uniform and a confiscated German pistol, the pictures appear to show the liberation of Mauthausen, one of the Nazis’ cruelest concentration camps. In graphic detail, they offer proof of the emaciated conditions of survivors, with their apathetic expressions and jutting ribcages, along with piles of corpses discovered by the Allies.

“I can’t believe human beings would treat others like that,” Aguilar said, his voice catching in his throat as he spoke on the phone. “Prisoners — they’re not supposed to be tortured to death.”

Aguilar, a Vietnam veteran, said the images reminded him of the American prisoners who were mistreated during the war in which he served. He called the Journal and offered to provide the photographs for safekeeping in the hope that they could be of some use.

“I didn’t want to throw them in the trash,” he said. “They’re history — World War II history, you know. I wanted somebody that could use them.”

Ken Parker was better known for the “girly pictures” of scantily clad models he took in the 1950s and ’60s — some of which still can be found on the internet — than for his war photography. But the photo prints found at the back of his daughter’s cupboard indicate that, for at least a few days in the waning moments of World War II, he became a witness to history, helping record the aftermath of some of the worst Holocaust atrocities.

Mauthausen — the hub of a network of smaller death camps outside of Linz, Austria — was notorious for its cruelty. It had all the horrors of Nazi sadism seen at many other concentration camps: a functioning gas chamber, torture instruments and evidence of grotesque medical experimentation. Other horrors were unique to Mauthausen: Prisoners were forced to carry 50- to 60-pound rocks up 186 steep, uneven steps from a quarry. Sometimes an officer would shoot a prisoner, toppling the rest like dominoes.

As the eventual outcome of the war became apparent, the camp’s leadership considered moving the remaining 18,000 prisoners into a tunnel system and sealing the exits. Instead, the SS simply abandoned the camp. The Third United States Army arrived on May 5, 1945, to find prisoners milling about in various states of starvation.

“Mauthausen, for a person going in, was absolutely bedlam,” Richard Seibel, the U.S. Army colonel who took charge of the camp after liberation, said in an interview recorded by the Dayton Holocaust Research Center in Dayton, Ohio, in 1989. “We had no water — everything had been disrupted before we got there — no water, no sewage, no food, no power, nothing. And here are 18,000 people being corralled, if you will, by combat troops who had no experience in handling a situation of this kind.”

“I’ve always heard stories about the Germans always trying to deny that they treated the people like that. Well, there’s proof in those pictures.”

Into this chaos walked Parker, who joined the war effort at 34, having already started a successful photography business in the Midwest. He easily endeared himself to colleagues, picking up nicknames like “Little Iron Man” for his compact size and tenacity, and “Tony” for his tan skin and slicked-back hair.

Before his deployment to Europe, Parker earned a reputation as a ladies’ man. He would sneak away from his Army base in Missouri and use a car he had hidden to hit the town and pick up women, according to his daughter.

As a member of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, a technology and communications division, Parker was assigned to document the U.S. combat mission, tailing Gen. George S. Patton and his troops through the Battle of the Bulge before arriving at Mauthausen.

With his camera — he favored a 35mm Nikon — Parker became involved in the documentation effort undertaken by the Allies for the twin purposes of prosecuting the Germans for war crimes and alerting the public to atrocities they had been only dimly aware of, if at all.

American generals made a point of publicizing what they saw in the camps. Patton ordered the entire town of Weimar to march through Buchenwald so its residents could see the piles of emaciated corpses and a lampshade made of human skin, among other gruesome sights. Encountering the camps, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander, ordered camera crews to film them as evidence of war crimes.

“It was as if the liberators, coming originally from Eisenhower, predicted the phenomena of Holocaust denial,” said Judith Cohen, chief acquisitions curator of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington, D.C. “And Eisenhower said he wanted documentation so that people wouldn’t attribute this to propaganda. That’s an amazing thing, because, of course, we see Holocaust denial left and right these days.”

In sending the photographs to the Journal, Aguilar said he had the same thought.

“I’ve always heard stories about the Germans always trying to deny that they treated the people like that,” he said. “Well, there’s proof in those pictures.”

According to Parker family lore, some of his photos ended up in the hands of prosecutors at the Nuremberg trials.

Some of Parker’s pictures also made it into the USHMM Photo Archive, courtesy of Seibel. One of them, shown here on the top right, Cohen recognized as a particularly iconic image — a picture of a soldier speaking with female survivors. In the archive, however, the photos are missing the photographer’s name. While other members of the Signal Corps went on to win widespread fame, including movie director Frank Capra and film producer Darryl F. Zanuck, Parker remained largely anonymous outside the world of Hollywood glamour photography.

Emaciated prisoners in a bunk in Mauthausen shortly after the camp was liberated.

Cohen said large amounts of historically significant material — diaries, photographs and other documents — still are stored in people’s homes, as Parker’s photos were.

“There’s an amazing amount of material still in private hands,” she said. “And we desperately would like to get it.”

“We are in a race against time,” she added.

Rabbi Michael Berenbaum, a Holocaust scholar at the American Jewish University in Bel Air, agreed.

“The reality is we’re now at one minute to midnight in the lives of the survivors, of the living witnesses,” Berenbaum said during an interview in his office. “Kids are emptying out their parents’ homes. Survivors are dying every day.”

Parker, according to his daughter, hardly ever spoke about what he saw during the war.

Moving to California in the 1940s after his Army service, Parker became a Los Angeles Police Department photographer for 11 years. He was let go for moonlighting as a photographer of pinup girls, a career that later earned him some acclaim in Hollywood.

But what he saw in Europe evidently left him with an unusually strong stomach for horrific images. Paula Parker said her father photographed the gruesome Black Dahlia murder scene for police in 1947 and kept copies, although she later threw them out, not fully aware of their value.

She recounted that once, during a family vacation, her father spotted a fatal train crash along the road and pulled over.

“My mother, she couldn’t stand blood anyway,” Paula Parker said in a phone interview. “She was so upset that my father would take time out of the vacation to take pictures of people dead.”

“After the war, nothing bothered him, I think,” she said. “My dad could do things that other people couldn’t.”

While the 13 Mauthausen pictures are unsigned and no independent source could confirm Parker shot them, his daughter — who saw the photos for the first time when she was about 30 — believes they came from his camera. He often developed his own photographs and kept duplicates as keepsakes, she said.

Moreover, the Mauthausen photographs were stored among hundreds of others she inherited that he shot over his lifetime. They showed family, friends, car races, golf games, Hollywood stars like Mae West and Bing Crosby (shot for Globe Photos), and images from other countries and of natural wonders that were taken for use in advertisements promoting American Presidents Line, a shipping company.

When she spoke with the Journal, Paula Parker said clearing out her father’s photos was a necessary part of preparing for her Nevada retirement, after working in Jewish delis around the San Fernando Valley for 38 years, sometimes holding three jobs at once. She said she and Aguilar threw out most of her father’s photographs but kept a select few.

She was ready to pass along the pictures of starving prisoners, barbed-wire enclosures and piles of corpses.

“Oh, I’ve seen them enough,” she said, “and I’ll always remember. What am I going to do, hold on to them?”

Created with Admarket’s flickrSLiDR.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.