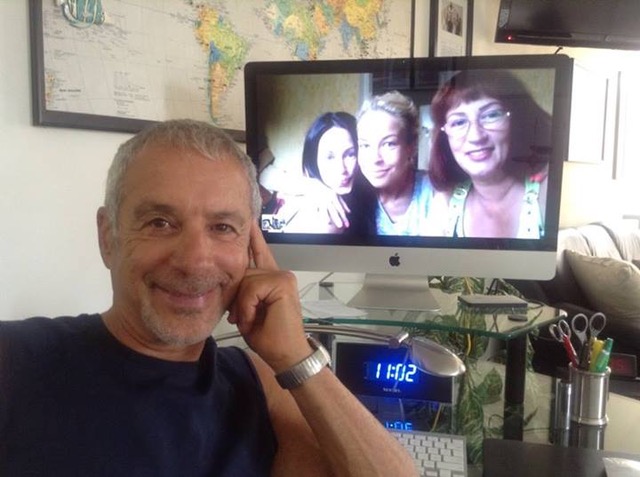

Johnny Herzberg Skyping with his newfound family members (from left), Diana Keisel, Marina Krumini and Liana Nechipasa in April 2014. Photo courtesy of Johnny Herzberg

Johnny Herzberg Skyping with his newfound family members (from left), Diana Keisel, Marina Krumini and Liana Nechipasa in April 2014. Photo courtesy of Johnny Herzberg

“Liana?”

“Johnny?”

Tears streamed ivown Johnny Herzberg’s face as he stared at his computer in his Playa del Rey home on March 25, 2014. On the screen via Skype, also in tears at her home in Amatnieki, Latvia, was his first cousin, Liana Herzberg Nechipasa, then 57 years old. It didn’t matter that they both had to struggle to communicate in their respective languages. Johnny, then 65, was meeting his only living relative for the first time.

Growing up with two Holocaust survivor parents, Ure and Ilse Herzberg, now deceased, Johnny had never missed having an extended family. His parents rarely talked about their ordeals in ghettos and camps, or about their relatives, including their former spouses and children, who had all been murdered by the Nazis — although Ure never received confirmation of his younger brother Joseph’s death. And Johnny seldom asked.

“My life was full,” Johnny said. “My parents were the most incredible parents.”

But after Johnny talked with Liana and days later Skyped with her daughters — Marina Krumini, then 28, a fluent English speaker, and Diana Keisel, then 39 — something changed.

“I got emotional for the first time in my life with people,” he said.

Five months later, Johnny was on a plane to Latvia.

Johnny discovered his cousin through Restoring Family Links, a collaborative program of the International Red Cross Committee (ICRC) and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies worldwide, including Magen David Adom. The service assists individuals who are seeking information about loved ones separated by armed conflict, natural disasters, migration or other humanitarian crises. For searches related to the Holocaust and World War II, the program also works in conjunction with various museums and archives, as well as the International Tracing Service in Bad Arolsen, Germany, which the ICRC headed from 1955 to 2012.

Those eligible to take advantage of the Holocaust and World War II tracing services include survivors seeking documentation about their own experiences and individuals searching for information about missing family members, wartime friends or rescuers.

“Family is defined very broadly,” said Kerry Khan, manager of International Services and Service to the Armed Forces for the American Red Cross Los Angeles region. But, she emphasized, the clients must have had a specific relationship with the person they are seeking to connect with — or determine the fate of — from sometime between 1933 and 1957. These are not genealogy searches.

Johnny never felt compelled to delve into his father’s history. But on a trip to Latvia in September 2013, he found himself emotionally overcome while touring the Riga ghetto, where his father had been confined and where his mother had been sent from her home in Germany. At the guide’s suggestion, he visited the Jewish Holocaust Museum Center.

“I was curious about my father’s history,” he said. “I never thought I could find anyone alive.”

Three months later, Johnny received an email stating that his father’s middle brother, Joseph, had survived.

Johnny remembered that in the early 1970s his father had unexpectedly received a letter from Joseph. It was always too dangerous for Ure to visit Latvia, but the two corresponded until early 1982, when the letters ceased and Ure assumed Joseph had died.

At the Center’s recommendation, Johnny contacted the Los Angeles-region headquarters office for the Red Cross in Westwood, where he met with volunteers in the Restoring Family Links program.

In February 2014, Johnny received documentation showing his parents had been confined in the Riga and Lipau ghettos in Latvia and the Fuhlsbuettel concentration camp and Kiel labor camp in Germany. Before the war’s end, they had been transported by the Red Cross to Sweden, where they married.

At home, while filing documents for the search, Johnny came across a letter he had received in 1975 — and forgotten about — from Joseph’s daughter, Liana, which a friend had translated into English. It included her address — 12 miles from Riga — through which the Latvian Red Cross located her.

By connecting with Liana and her family, Johnny was able to learn that Joseph had survived the war fighting for the Soviet Union in a Latvian army regiment. In 1947, Joseph was convicted of a political offense and exiled to Siberia. Freed upon Soviet leader Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953, he returned to Latvia, where he married and where Liana was born in 1956.

The Herzberg cousins remain close. Johnny visited Latvia for a third time in 2015. Marina came to Los Angeles in October 2014 with her husband, Alexei. The two visited again this past September.

“It’s absolutely a miracle that at this phase in my life I have this family that I can talk to all the time,” Johnny said. “I think it’s the biggest gift.”

“It’s absolutely a miracle that at this phase in my life I have this family that I can talk to all the time.” — Johnny Herzberg

Today, more than 70 years after World War II ended, tracing requests related to the Holocaust and World War II continue to rank among the top five conflicts, countries or regions that the Restoring Family Links program receives at the national level. The others include the Somali conflict (1991 to the present), African migration, the Democratic Republic of Congo civil war and the Persian Gulf War (1990 to 1991). In the United States, according to the Restoring Family Links Holocaust and World War II national database that goes back to 1990 — although the service has been available since 1939 — official requests for searches have been submitted for 44,694 people. For the most recent fiscal year (July 1, 2016, to June 30, 2017), requests for 99 people were submitted nationally. Of those, 36 came from the Los Angeles office. These searches will continue, said Los Angeles International Services manager Khan, “as long as somebody needs it.”

These days, in-person reunifications or reconnections are rare, but survivors are still seeking information on the fate of loved ones. Sometimes the results, even when expected, can be disheartening.

Susan Gati — named Zsuzsanna Tandler at birth — was 4 years old when her father, Imre Tandler, left their apartment in Budapest, Hungary, in 1943 to report for forced labor. She never saw him again.

Susan survived the remainder of the war living as a non-Jew with an aunt, the aunt’s non-Jewish husband and their two children. During that time, her mother, Antonia, hid in various places. They reunited after liberation.

Susan knew her father had been interned at the Bor work camp in Yugoslavia. After the war, a friend told her and Antonia that he had been deported to Germany, where he died. “I didn’t know the details,” she said.

Growing up with no memories of her father, only a few pictures and some comments her mother, aunt and cousins occasionally offered, Susan always felt the loss. “He was a good person, a nice person, hard-working,” she was told. “That’s all I knew. I don’t have a father.”

When Susan was about 14 years old, she saw a man who resembled her father walking toward her on the street. After he passed, she ran after him, yelling his name. He didn’t respond. Overcome with embarrassment, Susan ran into a nearby building and sobbed.

In 1968, Susan immigrated to the United States, settling in Los Angeles. Her mother visited occasionally, joining her permanently in 1982.

All those years, Susan continued to think about her father, but Antonia couldn’t talk about him. “It was very painful for her,” said Susan, who keeps a photograph of her father atop her dresser.

In August 2016, 13 years after her mother’s death, Susan attended a meeting of Café Europa, a social club for survivors, in which longtime Red Cross volunteer Bob Rich presented a program about Restoring Family Links’ Holocaust and World War II tracing services.

Susan filled out a questionnaire and was soon contacted by Rich to provide whatever documents she had. Six months later, she learned that, on Nov. 9, 1944, her father had been transferred from Bor to Flossenburg, a concentration camp in northeastern Bavaria, Germany; and on Dec. 3, 1944, he was deported to Hersbruck, a subcamp of Flossenburg, where he died on Jan. 4, 1945.

“It was sadness,” she recalled when she recently looked at the documents. “And it was so close to the date of liberation.”

Susan is grateful for the work of the Red Cross in finding where her father died. Still, she said, “You cannot reverse time. I knew they couldn’t give me an answer that he was alive.”

For other survivors helped by Restoring Family Links, confirmation of a loved one’s fate can bring peace.

Max Stodel, 94, was almost 19 when he was deported from Amsterdam on April 2, 1942, to the Kremboong labor camp in the northern Netherlands, leaving his young wife, his father and his six older siblings and their families. His mother had died in 1939.

After Kremboong, Max was sent to the Westerbork transit camp and another transit camp in Bissingen, Germany. He was interned in four concentration camps: Blechhamer, Gross-Rosen (after a two-week death march), Buchenwald and Klein Mangersdorf. He was liberated by American soldiers in the southern German village of Salach on April 30, 1945, at age 22.

Max then returned to Amsterdam. In March 1946, he received confirmation from the Office of National Security in The Hague that his father, wife, three of his four sisters and two brothers had been murdered by the Nazis. While he assumed his sister Rachel had met the same fate, he didn’t know.

Through the years, Max sometimes couldn’t sleep, worrying about what happened to Rachel, her husband and their daughters, Betty and Mina. Max remembered that Rachel was always happy. “She always visited my mother with her children,” he said. “We were a real family.”

In October 2016, after Max had submitted a search through the Red Cross office in Westwood, he learned that Rachel and her daughters were murdered at Auschwitz on July 26, 1942, as was her husband, Isidore, on Sept. 30, 1942.

“I thanked them, I thanked them,” Max said of the Red Cross.

“Before I die,” he added, “I wanted to know that my family was complete. It made me at peace. We were a very, very close family.”

For more information or to initiate a Restoring Family Links search from the Los Angeles area, call 310.477.5176 or email IntlTracing.LosAngeles.CA@redcross.org.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.