The credits were rolling when it hit me: “The Post” was over. Time to go home. “Why am I still sitting here?” I looked around and saw others still sitting in their seats. “Why are they still sitting here?” “Why are we all still sitting here?!”

In my opinion, the answer is in the Bible.

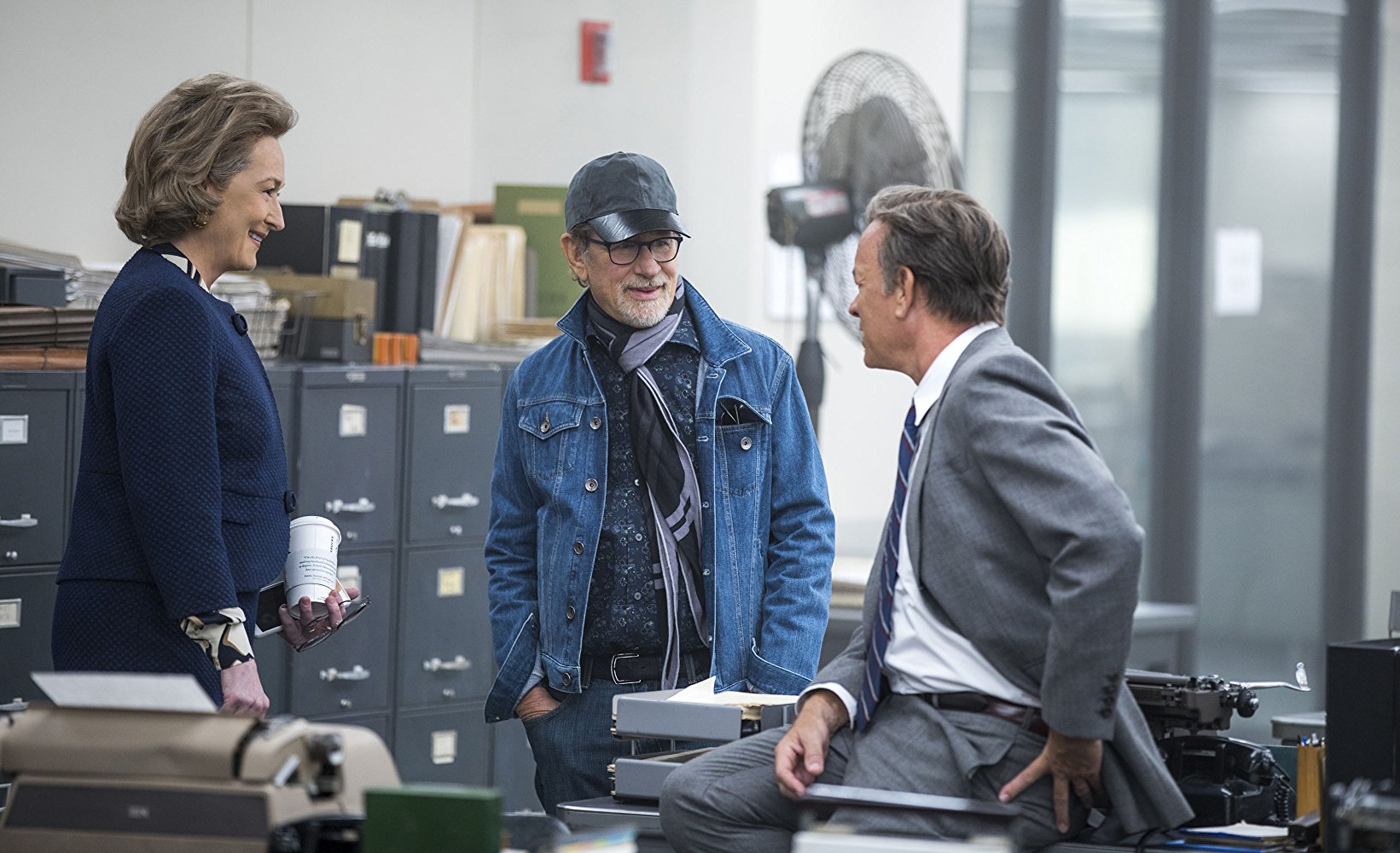

It is accurate to frame Steven Spielberg’s “The Post” as a retelling of the 1971 Pentagon Papers drama, but it is also overly simplistic. Spielberg transforms a historical narrative into a profound commentary on American culture, partially conveyed by the choices made for the beginning and the end of the film.

Stories usually open with “Once upon a time” and end with “The End.” The soft ambiguity of “Once upon a time” signals that whatever preceded the story is unimportant. Correspondingly, the hard certainty of “The End” says that everything important to the story has been told. The narrative exists only in the space between “Once upon and time” and “The End.”

The Bible does the opposite.

It starts with a jarringly definitive “In the beginning” and it ends so gently that the narrative is never formally closed. It follows that the Bible, by its narrative structure, is signaling to the reader that the Bible is important from The Beginning — it has always been important. More significantly, the teachings of the Bible endure long after the story ends, — it always will be important.

Spielberg faced a dilemma about the beginning of “The Post.” When does the story of the Pentagon Papers begin? The first moment of this story is a finite place and time. But which moment?

“The Post” begins its story in Vietnam. Daniel Ellsberg, the man who eventually leaked the Pentagon Papers to the press, is on the battlefield documenting the war. A soldier notices Ellsberg and wonders aloud, “Who’s the longhair?” meaning, who is the hippie civilian?

That phrase stuck with me because Ellsberg is an outsider and is identified by his long hair. For the duration of the film, the outsider is the publisher of The Washington Post, Katharine “Kay” Graham, played by Meryl Streep. She is an outsider in a corporate world dominated by men and, as a woman, she is also identified by her long hair. Graham’s journey in the film is the story of how and when she found her voice as a strong, confident, trailblazing woman who confronted and stood up to a powerful White House.

In a movie with consequences of biblical proportions, Spielberg seems to take a cue from the Bible.

There is a third outsider identified by her long hair in “The Post.” Meg Greenfield, played by Carrie Coon, is the only woman on the editorial board of The Washington Post. As the film rises to its crescendo, Greenfield is holding court in the newsroom. She is on the phone with a contact at the court, and she is relaying everything she is hearing. Greenfield has the attention of the entire newsroom. The air is silent and heavy with dramatic pause when a middle-aged white male editor barges into the newsroom and steals her thunder. Reading from a slip of paper, he exuberantly announces victory. For a moment Greenfield’s face falls, but she composes herself and gets another chance to shine a few moments later when she dictates Justice Hugo Black’s forceful opinion — uninterrupted.

In a profound film about women’s empowerment, this moment was a reminder that we adapt and evolve slowly. Kay Graham may have found her voice but women could still expect to be interrupted by men oblivious to the shifting social environment around them.

“The Post” could have ended with the euphoric reaction to the Supreme Court ruling in favor of the media against the president. But Spielberg ends by setting the stage for the Watergate scandal. In a movie with consequences of biblical proportions, Spielberg seems to take a cue from the Bible and opts for a gentle, open-ended final scene.

Long after the Pentagon Papers were published, freedom of the press remains an issue. Long after Kay Graham found her voice, treating women fairly remains an issue. Long after Meg Greenfield was interrupted, respecting women remains an issue.

“The Post” does not conclude with finality because, just like the Bible, it is the beginning of a long struggle, not a story about one particular struggle. And that explains why we lingered in the theater watching the credits roll.

Eli Fink is a rabbi, writer and managing supervisor at the Jewish Journal

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.