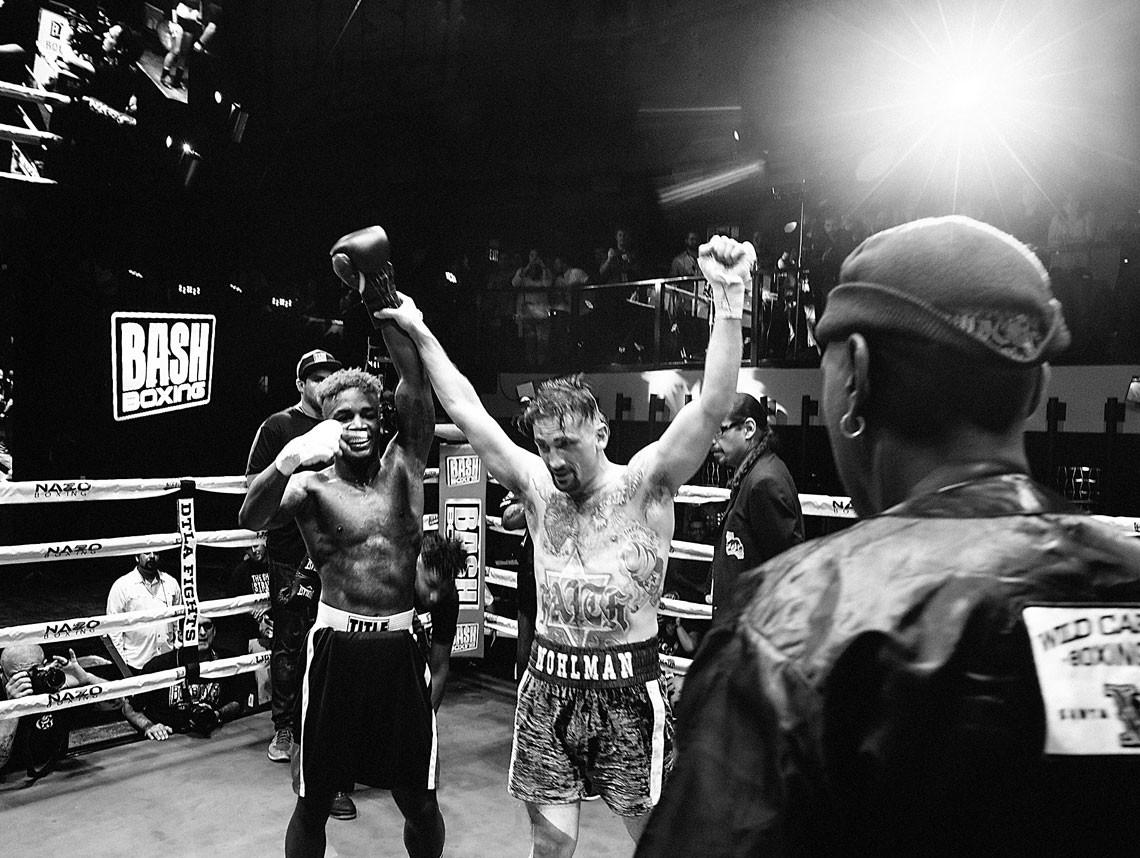

Zach Wohlman (center), known as “Kid Yamaka,” fought Matt Murphy to a draw on June. 22. Photo by Scott Leon

Zach Wohlman (center), known as “Kid Yamaka,” fought Matt Murphy to a draw on June. 22. Photo by Scott Leon On a recent Thursday night downtown at the Exchange LA, Zach Wohlman, aka “Kid Yamaka,” stood at the center of a boxing ring, awaiting the decision.

He was ready to be declared the winner, he told the Journal later, but the judges felt otherwise, ruling the June 22 match against Matt Murphy a draw. The crowd booed loudly, Wohlman remembers, and he put his hands to his head in shock.

Still, he knew that just getting back in the ring was a victory, considering the dramatic roller-coaster ride he’d taken the past few years.

Wohlman, 29, grew up in the San Fernando Valley. He started boxing while in military school, where he was sent as a teenager. He fell in love with the sport shortly after, finding in it a discipline through which he could funnel frustrations from a difficult childhood.

His work ethic and ring smarts were noticed by Boxing Hall of Famer Freddie Roach. With Roach’s help, Wohlman won L.A.’s Golden Gloves amateur competition by age 20 in 2009. A year later, he turned pro as a welterweight, and has since won 10 of his last 14 fights, two of them by knockout. But fierce as he is, vanquishing his inner demons has proved difficult.

Two years ago, after breaking his jaw while sparring at the gym, Wohlman developed an addiction to OxyContin — a common hazard for fighters. Last summer, he said he was “at the end of his rope.”

The ups and downs of addiction were wreaking havoc on his friendships. A fight scheduled for last August was canceled when he told his coaches he wasn’t ready. In the past, Wohlman had used daily prayer to help him stay sober. Now, he said, he asked, “God, remember when we were friends?” He had every intention of getting clean but couldn’t seem to get off the merry-go-round.

He has now been clean and sober for more than 4 1/2 months.

In a macho sport, one’s cultural background is not just a factor — it’s a point of distinction. When his coaches learned he was Jewish, the first thing they thought of is a yarmulke, which is how Wohlman’s nickname came about. Though he is not devoutly religious, Wohlman is proud of his Jewish background — a large Star of David tattoo covers most of his abdomen and several other stars adorn his boxing robe. Two of his grandparents were Holocaust survivors, and he holds on to his identity with the awareness that “there aren’t that many of us left.”

Other than Wohlman, there appears to be only a handful of other Jewish professional boxers active in the United States. A dearth wasn’t always the case. From the late 1920s until the end of World War II, dozens of Jews went into boxing as a way to make money at a time when the doors to higher education were closed to them. Between 1910 and 1940, there were 26 Jewish world champions, according to Allen Bodner’s “When Boxing Was a Jewish Sport.”

Wohlman loves investigating that history. Last summer, he carried around the comic book “The Boxer” by Reinhard Kleist, a true story of a Polish Jew who was forced by SS officers to fight while imprisoned at Auschwitz. He went on to become a professional boxer in the U.S. in 1948 just as Jewish boxers were leaving the sport.

Wohlman said he finds a source of strength in “seeing the struggle that the people of my blood line have gone through.” Bar mitzvahed at the age of 20 at the addiction treatment center Beit T’Shuvah, where he sought treatment for drugs and alcohol, he said he likes the ritual of slowing down on Shabbat. But since leaving Beit T’Shuvah, he said he has been unable to find the right place or a community in which to spend Shabbat.

If anything, boxing itself is his spiritual practice.

“Being present, being in the moment, for three minutes at a time [in boxing rounds], you can’t buy that type of self-awareness,” he said. “That adrenaline, you can’t match it.”

Although Jews in the early 1900s found boxing as a way around closed doors, for Wohlman, it worked the other way around. Boxing has opened up a world of new opportunities.

A young filmmaker, intrigued with Wohlman’s talent and gift for quotable phrases, created a short film titled “Kid Yamaka,” which captures his hardscrabble past and the nuances of his relationship to a violent sport. In the film, director Matt Ogens interweaves Judaism and boxing using visual metaphor, cross-cutting the wrapping of Wohlman’s fists before a fight with images of him binding them with tefillin.

The 14-minute film was used to sell an eight-part TV series centered on Wohlman. Shot in the spring, the series follows Wohlman around the world, meeting professional fighters in far-flung places, positioning Kid Yamaka as a sort of “Anthony Bourdain of fighting,” Wohlman said.

The series, called “Why We Fight,” also reflects Wohlman’s personal journey. As he connected with fighters in Cambodia and Mongolia, helping to relay their stories, he also squared off against himself, his addiction and his past. The docu-series will be out this fall on Complex’s Go90. In addition, Wohlman is writing articles for Vice online.

And as for boxing — he’s already training for his next fight.

AMIE SEGAL is a documentary producer living in Los Angeles.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.