Staff Sgt. Paul Rabinek (date unknown).

Staff Sgt. Paul Rabinek (date unknown). While growing up in the San Fernando Valley, twins Susan Rabinek Birnberg and Judy Rabinek Felkai heard stories of their father’s wartime experiences. Paul Rabinek had tried to enlist in the United States Army, but the Austrian-born young man was deemed a “spy” and rejected. Later drafted, he landed in Normandy as part of the D-Day invasion, served as an interrogator, lit cigarettes with foreign currency and acquired a German motorcycle.

But to Susan and Judy, now 59, these exploits seemed grand and glorified. And forever unknowable. Paul Rabinek had died of a heart attack in 1964. And his military records, they were told, had been destroyed in the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis.

“Losing Daddy at 5 years old, we have a void,” Susan said. “It’s not just empty. It’s a black hole.”

Their older siblings don’t share that emptiness. Their brother, David, was 14 when their father died. “He remembers the person,” Judy said. So does their sister, Elisabeth, who was 11.

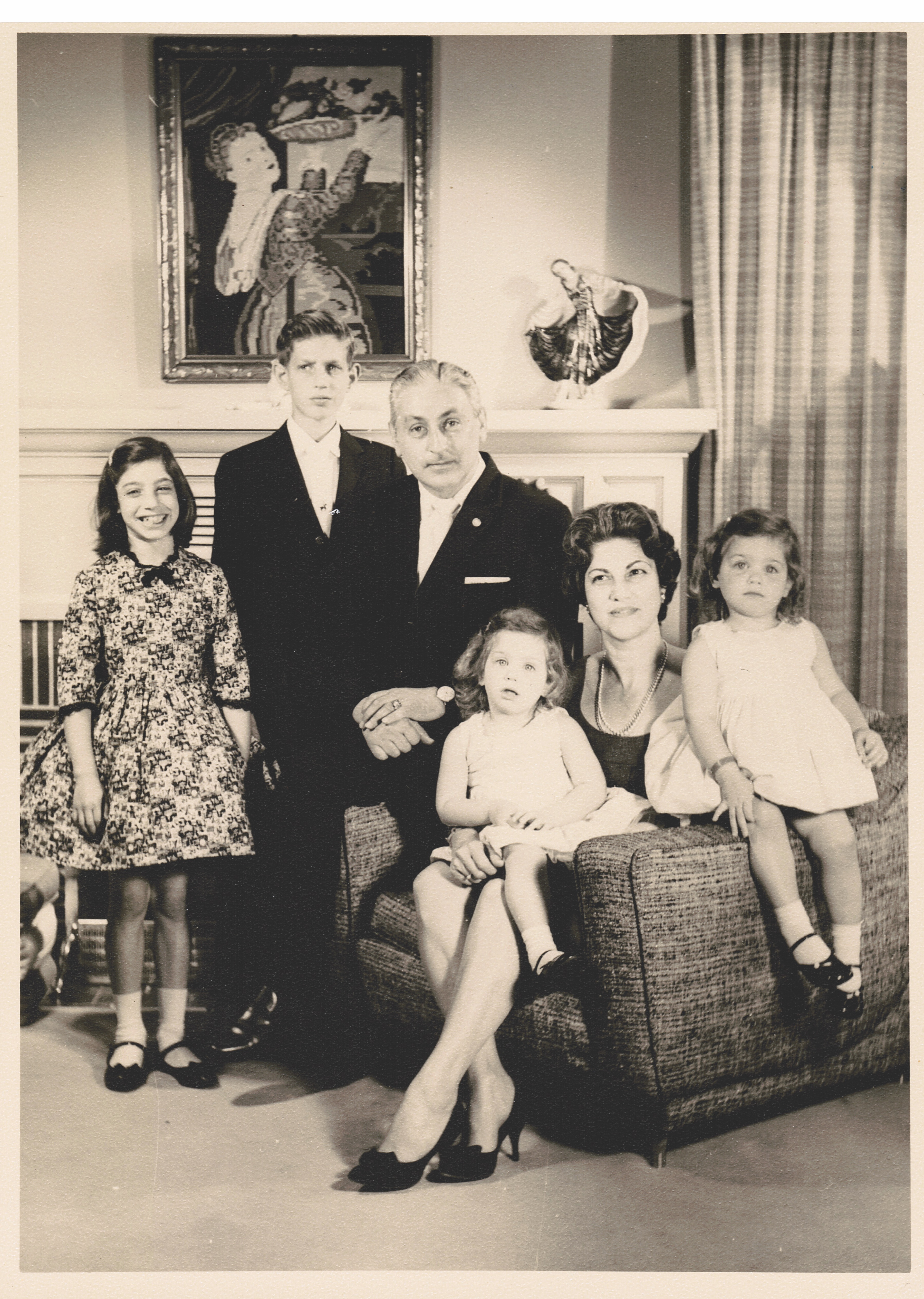

Over the years, the emptiness remained, though their mother, Bernice, who died in 2004, spoke often — and lovingly — of Paul. They knew he was kind, personable, smart and industrious, a man who enjoyed life. They had photographs and home movies.

They knew he was born in Vienna on Jan. 25, 1914, into a wealthy family from Paks, Hungary, and later helped run their successful textile business. But after Kristallnacht, the family hastily retreated to Paks, and two years later, Paul and his sister, Ann, immigrated to New York, arriving on Jan. 24, 1940. Paul had $5 and a suitcase full of tailor-made clothes.

After World War II ended, when Paul received word that his parents had survived, he wanted to take a jeep to Soviet-occupied Budapest, Hungary, to fetch them. Instead, his commanding officer, fearing he would be shot or captured, sent him home.

But for Susan and Judy, the personal connection was always missing. “I wanted so badly to know my father,” Judy said.

That began to change last August when a client of Susan’s husband randomly handed him a newly published book titled “Sons and Soldiers: The Untold Story of the Jews Who Escaped the Nazis and Returned With the U.S. Army to Fight Hitler” by Bruce Henderson. These soldiers, who trained at Camp Ritchie in Maryland, came to be called Ritchie Boys.

Susan wasn’t past the introduction — where she read that German citizens residing in the United States were considered “enemy aliens,” that they were later inducted into the Army, that they already knew the enemy’s language and culture, that they were trained to interrogate German prisoners of war — before she silently exclaimed, “Oh, God, I think Daddy was a Ritchie Boy.”

She texted her siblings — “I think Daddy was a Ritchie Boy” — asking them to bring over any pertinent documents and photographs, ASAP.

Soon, Susan’s dining room table was covered with papers, their father’s war pictures and Paul’s little black address book, which Judy had found. Inside, Susan saw a listing for Guy Stern — whom she recognized as one of six Ritchie Boys profiled in Henderson’s book —with a St. Louis address.

The next day, Judy discovered a talk on YouTube that Stern had given at the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kan., on June 6, 2014, titled “My Life as a Ritchie Boy.” She texted Susan: “We found the premier Ritchie Boy. He remembers everything.” Plus, she added, “He’s alive.”

Susan tracked down Stern in Michigan, where he was — and is currently — director of the Harry and Wanda Zekelman International Institute of the Righteous at the Holocaust Memorial Center in Farmington Hills. “Was your father, perhaps, Paul?” Stern asked. Susan began to cry.

Stern told her that he and Paul trained together at Camp Ritchie and were stationed together in Europe. He confirmed the story she had heard from her mother, about how her parents met on Dec. 25, 1945, when, according to family lore, Paul crashed the New York wedding of his commanding officer, Master Sgt. Kurt Jasen, in which their mother was a bridesmaid. “It was love at first sight,” Stern said.

Stern also confirmed that he and Paul had acquired motorcycles. They found them abandoned in a factory the Allies took over in Andernach, Germany, in March 1945. (Stern later added, “Since we also were adventurous young men, we tried out riding them, which we had never done before. No fatalities were reported.”)

“Did you know that your father was a rascal?” Stern asked Susan. She wasn’t surprised.

Susan related the conversation to Judy, as both sobbed on the phone for half an hour. “This was such a release. A filling up. I don’t even know what to call it,” Judy said.

Susan then contacted Henderson, to tell him about her father and thank him for making the “miraculous” connection. She asked for help in retrieving her father’s war records, and Henderson contacted unofficial Ritchie Boy historian Dan Gross, who constructed a basic timeline of his service.

Paul entered Camp Ritchie in April 1943, was promoted to sergeant eight months later, and was released on Jan. 20, 1944. Eight days later, he departed for Europe, one of the six members of IPW (Interrogation of Prisoners of War) Team 41, attached to U.S. First Army headquarters.

Susan and Judy continued learning about the Ritchie Boys.

Gross’ research had found that 11,637 servicemen, under secret orders, completed the eight-week training program at Camp Ritchie. Of those, 2,208 were born in Germany and 583 in Austria. An additional 520 or so German-born and 130 Austrian-born servicemen who were urgently needed overseas, were shipped out before completing the course.

The German-speaking Ritchie Boys were trained primarily in interrogation but also in other subjects, such as terrain intelligence and aerial photo interpretation. Most challenging was the Order of Battle class, in which they had to learn encyclopedic details about the German military, including, Henderson wrote, “unit designations, terms and abbreviations, their arsenal of weapons, the nature of their supply system, and their chain of command.”

“Losing Daddy at 5 years old, we have a void. It’s not just empty. It’s a black hole.” — Susan Rabinek Birnberg

Trainees then were assigned to various Army units, serving on the front lines interrogating POWs, obtaining information about enemy troop levels, movements, and physical and psychological well-being.

A postwar study that Henderson cites in his book, states “the consensus among division intelligence officers was that 58 percent of all combat intelligence gathered by the U.S. Army in the European Theater of Operations was the product of Military Intelligence teams. The majority, 36 percent, came from German-language interrogations conducted by IPW teams.”

On Nov. 7, 2017, the Rabinek clan traveled to Detroit to visit Stern and attend a talk by Henderson at a Kristallnacht event sponsored by the Jewish Community Center of Metropolitan Detroit in suburban Bloomfield Hills.

Family members included Judy and her three children, Elana, Paul and Aaron; Susan and her husband, Johnny; and their sister, Elisabeth Seftor, and her husband, Richard. (Their brother, David, and Susan’s two daughters were unable to join them.)

At dinner that night, Stern pulled out a paper covered in handwritten notes and talked at length about Paul, including these recollections:

Paul was neat, often reprimanding Stern for leaving his socks in the jeep. He was always late. He was an excellent driver and the best mechanic around.

Paul didn’t get angry and never showed fear, even when given orders to land in Normandy the day after the invasion. He was also a risk-taker, procuring Calvados (apple brandy) from local farmers, which he sold to the soldiers. He also brought them fresh eggs.

Paul didn’t complain. He always accomplished what he set out to do. He didn’t change his name, as some Jewish soldiers understandably did, and he kept the H (Hebrew) on his dog tags.

“Being Jewish, it was not like you were an ordinary POW,” Stern later explained. “If you were unmasked as a German Jew, some commanders would put you in POW camps that resembled concentration camps, or some [POWs] were killed.”

Stern also told them that when Paul walked into an interrogation, he had a habit of slowly rolling up his sleeves. That resonated with Judy. “I don’t know if I really saw Daddy doing that, but I could see Daddy doing that,” she said.

But perhaps the favorite story, which Stern told in his 2014 talk and which Henderson has included in an updated Kindle edition of his book, is about the soldier who became known as “Shortcut Paul.”

As Stern related, Paul was driving Jasen and Stern back from delivering a message to headquarters one day when he opted to take a shortcut. Soon, they heard German-speaking voices. “Get us the hell out of here,” Jasen ordered.

Paul backed up the jeep, which promptly died. “Out of gas,” he reported. Jasen angrily reminded him about the canister of gas in the back. “Yes, but I traded with a Normandy farmer for some Calvados,” Paul said.

“Put the Calvados in the tank,” Jasen shouted. At this point, recalled Stern — who said he was “scared beyond recognition” — the jeep’s engine miraculously started.

The stories continued the next day, when the Rabineks visited with Stern at the Holocaust Memorial Center, touring the museum and donating toys from a concentration camp that Paul had brought back from the war. (The family doesn’t know how or where he acquired them.)

On the family members’ last day in Michigan, they attended a talk by Henderson about “Sons and Soldiers” at the JCC of Metro Detroit’s annual book fair for Kristallnacht Remembrance Day.

During their three days in Michigan, the Rabinek family learned new stories about Paul and received clarification of familiar ones, gaining new insights into the father, grandfather and father-in-law that all but Elisabeth barely or never knew. But for Susan and Judy, the need was deeper. “It was like getting air,” Judy said.

Now, four months later, the twins feel more settled, with a fuller, more nuanced picture of their father. “I see him as a whole person, not a fictional character,” Susan said. As for Judy, it brought her to “a real place.”

Moving forward, they hope to continue the strong attachment they have formed to Guy Stern. “We’re mishpucha now,” Stern told them.

Susan and Judy also want to keep connecting with the children of the Ritchie Boys. So far, they have shared stories and photos with four. All of those they have contacted knew their father was an interrogator during World War II, but none knew he was a Ritchie Boy.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.