As we sit down to our Passover seders this weekend and retell the story of how we wandered in the desert to achieve our freedom, we are once again reminded that despite the passage of 3,000 years, people are still struggling to be free.

Soraya Alvarez (not her real name) is one of those people. In 1990, when she was just 2 years old, Soraya and her parents left their home in Durango, Mexico, and crossed the Sonoran Desert on their way to the promised land: America.

Alvarez was too young to recall the journey, but she related the following story that her father told her: During the family’s trek through the desert, their “coyote” — a man hired to help them cross — warned Alvarez’s father that United States Border Patrol agents were approaching.

“My father was carrying me and we were trying to hide behind these bushes, so he put me down behind the bush. But I started to cry and wouldn’t stop. When he looked down, he realized I was crying because there was a big cactus and I was being punctured by it.”

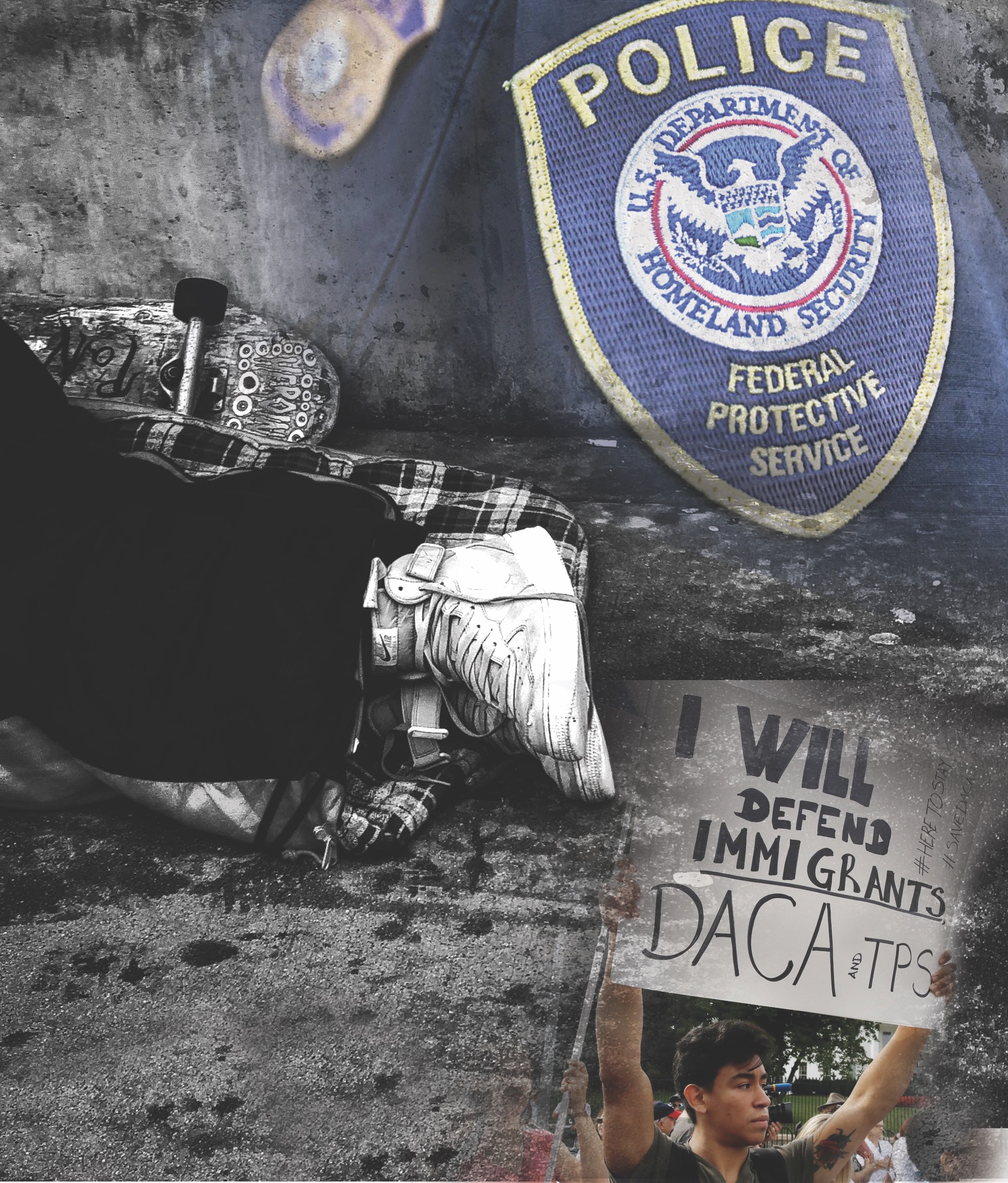

That incident could serve as a metaphor for Alvarez’s personal and professional life in America. Today, as an undocumented immigrant, she works for a nonprofit organization that advocates for the rights of immigrant youths — those punctured by U.S. immigration enforcement policies.

“We are fighting the good fight, pushing against the narrative that scapegoats immigrants,” she said. “We feel all immigrants should live with dignity and respect, regardless of where they come from.”

Alvarez shared her story as she sat in the boardroom of the downtown law offices of Stone, Grzegorek & Gonzalez, which specializes in immigration law and facilitated this interview. She chose to use a pseudonym and not state where she works for this interview, she said, because she fears for her parents.

Alvarez said her father came to the United States on a visa in the 1980s before she was born. He earned money by working in construction. Following her birth, he needed to make more money to support his family and came back to the U.S. to work again. “I didn’t meet my father until I was 2,” Alvarez said.

Her father loved America. He saw the opportunities available and wanted his daughter to take advantage of them. And so, he convinced Alvarez’s mother that their family should go there to make a new life.

Alvarez said she always knew growing up that she was undocumented. “My father always told me, ‘You’re in this situation because of us, and now you have to work twice as hard as anyone else.’ ”

Work hard she did. Alvarez was valedictorian of her 2006 high school graduating class at the Elizabeth Learning Center in Cudahy.

However, she was taken aback when she applied to colleges.

“I guess I was naïve,” she said. “I thought because I had good grades and was involved in all these organizations and clubs and I was volunteering, that somehow I would be able to get financial aid. But I realized that the situation was more difficult.”

“When I say it’s not my fault, my parents brought me here, I’m criminalizing my parents.” — Soraya Alvarez

Still, she persisted and earned a bachelor’s degree at Cal State Los Angeles. She then received a master’s degree in international relations at Chapman University.

Even after she qualified for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) in 2015, following President Barack Obama’s executive order, she lost her job at a nonprofit organization in May 2017, when her DACA status expired as she was in the midst of the renewal process.

“This was happening around the time the Trump administration came into power,” she said. “All the government offices were understaffed. And I guess a lot of lawyers feel threatened by the possibility of being audited, so they didn’t want to take the risk” of keeping her on.

Two weeks after she lost her job, Alvarez received her DACA renewal, which is now in effect through May 2019. It took her three months to find her current job.

“I was very concerned because I have student loans from my graduate studies, so I was really stressed out. I think my mental health really took a dive,” she said.

As it turns out, Alvarez is now the only undocumented immigrant in her family. Her 25-year-old brother was born in the United States, and when he turned 21 he was able to have their parents become permanent residents.

Alvarez said she’s not comfortable being labeled a “Dreamer” — the term often used to refer to DACA recipients. “Looking back, we were able to achieve so much as Dreamers, but I felt like we placed our experiences on a pedestal because we appear to the American public as educated.”

Growing up in America and assimilating into American culture have been positive experiences for her, she added, but at the same time she is concerned about many others who she sees as being left behind.

“When I say I’m not a criminal, I consider that to be very anti-Black, because so many Black people and other people of color have been incarcerated as a result of criminalization,” she explained. “When I say I’m not a terrorist, I feel like I’m also criminalizing the Muslim community. When I say it’s not my fault, my parents brought me here, I’m criminalizing my parents.”

Her parents are concerned about the potential legal ramifications of her activism.

“I’m not breaking any laws,” she said, “but I am going to rallies and speaking out and putting my name out there. It’s taking a risk. My parents caution me. They say, ‘We see on TV that activists are being rounded up.’ But I feel like our times require people to stand up and speak truth to power. And if I were to just give up and let things happen, I wouldn’t have a clear conscience.

“Because, U.S. residents are also being targeted and can be criminalized,” she said. “If ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] were to come and target me, they might try to target my parents as well. I’ve seen that happen with other people.”

She tries not to get caught up in what might happen to her in the future, even though she fears the Trump administration may abolish DACA. Instead, she focuses on her work and living in the present.

Her goal, she said, is “to change the hearts and minds of people who are on the other side, who continue to dehumanize us, criminalize us and scapegoat us for all the societal problems that exist.”

If there’s one thing she wishes she could do, it’s travel the world.

“I can only imagine what life would be like outside of these walls,” she said. “As someone who is really passionate about human rights issues around the world, it’s definitely something that I always think about.”

Alvarez said she might consider returning to Mexico one day “if we are not able to fix our situation here and find relief.

“I don’t feel like a prisoner per se,” she said, “but I would love to be able to go and explore one day without having to feel like I can’t.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.