Screenshot from Twitter.

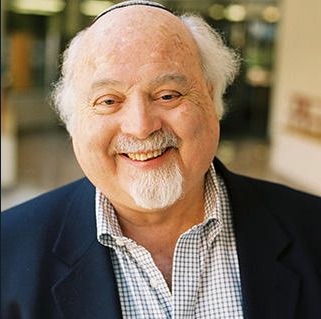

Screenshot from Twitter. Two generations of students at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTS) are mourning the passing on Nov. 24 of a challenging and beloved teacher, Rabbi Neil Gillman.

Beginning with his arrival from Montreal in the mid-1950s, Gillman was a commanding presence in the seminary community for over half a century. He was ordained by JTS in 1960 and earned his doctorate in philosophy from Columbia University in 1975.

He served as dean of the JTS Rabbinical School in the 1970s, during a period of transition when JTS debated women’s ordination, which it initiated in 1985. He was an early advocate for egalitarianism, and continued to teach and model an inclusive vision of Jewish thought and practice throughout his life.

Gillman also was a historian of JTS and Conservative Judaism, publishing a volume on the topic in 1993 and working with a committee to articulate the philosophy of Conservative Judaism in the 1988 volume “Emet V’Emunah.” He also wrote several volumes on how to define and justify belief in God through radical questions and sound philosophical considerations. His 1997 book, “The Death of Death,” examined Jewish beliefs about life after death.

You did not have to be an academic to understand his books. Gillman was forever the teacher in his writing, explaining difficult concepts in clear, down-to-earth language.

Gillman’s students will remember him most for the way he challenged them to think deeply about Jewish beliefs and practices and to create a Jewish theology of their own. They didn’t mind when he pointed out weaknesses in the way they were thinking because they knew that he cared deeply for them.

They also will remember lovingly the shock that Gillman evinced when a student said something that he found questionable or downright wrong — and how he would then prod the student into defending his or her particular belief rather than abandoning it. Gillman single-handedly transformed the education of future rabbis, educators and lay leaders from a passive study of other people’s thought into an exciting and significant struggle with one’s own. He did so with warmth, humor, wide erudition, analytic precision and genuine concern for his students.

I first met Neil Gillman at Camp Ramah in Wisconsin, where he taught me how to chant Eikhah, the Book of Lamentations, when I was 13. A year later, his wife, Sarah, taught me the first midrashic texts that I had ever seen.

Gillman later played a critical role in my life, persuading me to accept a fellowship and study for a doctorate in philosophy at Columbia while I was in rabbinical school at JTS.

He challenged them to think deeply about Jewish beliefs.

Subsequently, because we shared a deep love of both Judaism and of the philosophical questions that could either undermine it entirely or strengthen it significantly, we became frequent intellectual sparring partners, and I shall miss that immensely. One example: When I was working on the second edition of my book “Conservative Judaism: Our Ancestors to Our Descendants,” he and I spent many long-distance phone calls debating Abraham Joshua Heschel’s theology of revelation. As a result, I changed the way I categorized Heschel’s approach in the book — although, to this day, I’m not sure that Gillman was right about that!

We both wrote books on religious epistemology — the question of how we can know that our religious beliefs are true. Mine emerged directly from the world of analytic philosophy, while his included the insights of scholars of religious anthropology. It is through him that all of his readers, including me, learned to appreciate the role of religious stories (“myths”) and ritual practices in shaping what one believes and trusts.

We loved critiquing each other’s work, often with playful expressions of surprise that the other person could say or write such a thing.

We all will make Rabbi Gillman’s memory a blessing if we follow his lead in so deeply caring for one another and for our Jewish heritage that we are not afraid to question both, thus making our relationships and our Judaism truly matters of all our heart, all our soul and all our might.

Rabbi Elliot N. Dorff is rector and Sol & Anne Dorff Distinguished Service Professor in Philosophy at American Jewish University.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.