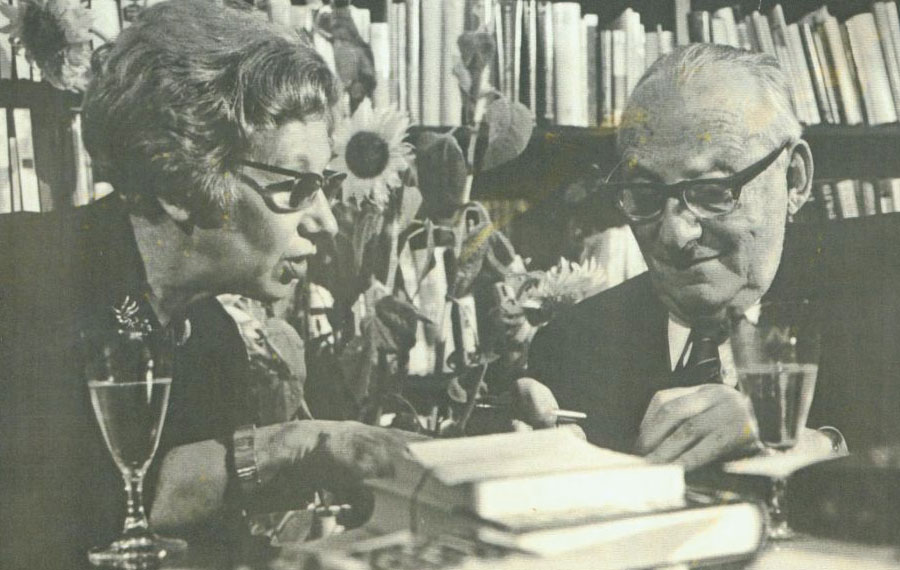

Eva Hoffe with Max Brod

Photo from Hoffe’s family archive

Eva Hoffe with Max Brod

Photo from Hoffe’s family archive The story of Eva Hoffe is a sad one. In essence, it is a long, sordid history of broken promises. It begins with Czech-Jewish writer Franz Kafka. Before passing away, he entrusted his friend Max Brod with a large collection of his manuscripts, instructing Brod to destroy them.

He did not.

Brod, in turn, left them to his secretary (and alleged lover) Esther Hoffe, with the instructions that she transfer them to a public archive in her lifetime.

She did not.

Thus they ended up in the hands of Esther Hoffe’s last living daughter.

For decades, Eva battled the Israeli courts for her right to Kafka’s manuscripts, stored in vaults in Tel Aviv and Zurich and (according to some individuals I asked) in a small, brown suitcase hidden somewhere in her squalid apartment.

Had Eva won her case, she would have sold the manuscripts for millions of dollars. But she lost. And then, in August, she died at the age of 85.

Reading of her death, it wasn’t her manuscripts that I thought of first. Rather, it was her cats. Before I knew of her as the keeper of Kafka’s lost work, I knew her as the cat lady of Spinoza Street.

It was years ago that I met her for the first time. This was back when I first moved to Tel Aviv. I didn’t know many people and would sometimes spend my afternoons wandering around the city — mentally mapping the streets and trying to get my bearings. It was during one of these walks that I happened into Trumpeldor Cemetery.

Minutes from the hectic commercial center of Tel Aviv, the quiet and dignified cemetery felt a world apart. The names inscribed on the graves sounded familiar to me. Nordau, Ahad Ha’Am, Arlozorov, Dizengoff, Bialik, Tchernichovsky – the politicians, poets, and leaders of Israel. Until then, they had been nothing more than street names to me.

As I continued my walk, I saw a familiar face pass by — an older woman with a scowl and a hunched back.

Back then, I was working at a small nursery school on Spinoza Street. My days were spent shaping Play-Doh, building with Legos, and taking the kids out to the small back garden to run around.

The woman I saw in the cemetery was familiar to me as the pair of peering eyes that sometimes glanced at us from a window high above our nursery school’s back garden.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons

I had never spoken to her, but I knew of her through local lore. It was Eva Hoffe, the much-maligned cat lady of Spinoza Street, and the unlikely keeper of Franz Kafka’s unpublished manuscripts.

She turned and saw me looking at her. It appeared that she recognized me as well. Slowly she made her way over to me. “You work at the preschool,” she said. “I can hear you very well from my apartment. The children make a lot of noise.”

The truth is, we could hear her too. More specifically, we could hear her cats.

She paused a moment, weighing what she wanted to say. I assumed it would be something unpleasant. My boss had never missed an opportunity to characterize her as a child-hating and crotchety neighborhood burden.

“You make a lot of noise,” she repeated. “But you make the children laugh. It’s lovely to hear to them laugh.”

This caught me off guard, but before I had a chance to respond, she took my arm and began pulling me with her. “Come,” she said, gesturing to a grave. “This is Max Brod. Today is his memorial. He was a friend of my mother’s.”

We stood in silence a moment as we looked at the grave. I don’t remember how much I knew then of her legal battles for Kafka’s manuscripts, or of the significance of her mother’s relationship with Brod. She didn’t bother explaining. After a beat, she said goodbye to me and walked away.

The next week at work, I saw Hoffe taking out her garbage during the students’ outdoor playtime.

We exchanged waves. My co-worker, Jenna, cocked her head at me. I explained how we had met and added that Hoffe was, surprisingly, a very sweet lady.

Jenna rolled her eyes.

This was to be expected. Those who worked at the nursery school thought of Eva the way my boss did. She had even managed to influence the thinking of the class mothers.

The issue was her cats. Back then, Eva’s shrieking cats could be heard from her windows at all hours. She must have had at least 20 of them in there, all fighting and bristling and mewing plaintively to be fed.

My boss so disliked having Eva as a neighbor that she led a small but determined campaign against her. She encouraged the class mothers to lodge complaints with the municipality about the cats, telling them to say that the presence of so many animals in a confined space had a detrimental effect on the health and well-being of their children (a complete falsehood). “Without more voices,” she would say, “nothing will be done.”

After a certain number of calls had been lodged, the city would come and clear out the cats, after which Eva would begin to collect them again.

At times, I would defend Eva’s right to her cats, but I was always met with the same response, which was that it wasn’t ethical to keep all those cats cooped up in there. I would tend to agree, but somehow I sensed that cat-activism was not the motivation behind the campaign. It was something else. My boss’ ire was aimed at Eva herself and the appeal to “think of the cats!” was unconvincing.

As I learned more about Eva’s case, I began to defend her right to her manuscripts as well. And for the same reason. The state’s case didn’t convince me.

The state argued that the Hoffe family had no legitimate right to Kafka’s manuscripts. Brod had specifically requested that they be placed in an archive. In disobedience to his wishes, the Hoffes had decided to cynically profit off of them through private sale.

But if the state was truly concerned with honoring the wishes of the manuscripts’ rightful owner, why not look to the source — to Kafka himself — who wanted them destroyed?

As a writer, I am always disturbed when the posthumous requests of authors regarding their own work are disregarded. The dead have few advocates, and the long-dead have none. The question of destroying the manuscripts was not part of the equation in the Hoffe case. As such, it seemed to me that this was a matter of two illegitimate parties battling over a piece of property which belonged rightfully to a fire pit.

Before I knew of Eva Hoffe as the keeper of Kafka’s lost work, I knew her as the cat lady of Spinoza Street.

If that was the case, why not rule according to “finders keepers” and let poor Eva keep her ill-gotten heirloom? The state of Israel surely had no greater claim.

Had she won her case, she would have made millions through the sale of the manuscripts. The highest bidder most likely would have been a national archive anyway. Israel would have lost a literary treasure, but Eva would be luxuriating in a gorgeous mansion, her cats strutting about happily, crystal dishes of food in every room and a servant making the rounds tending to the litter boxes.

But she lost and the work contained in the vaults was ordered to be transferred to Israel’s National Library.

In lieu of a truly legitimate claim to the manuscripts, one question considered in the case was that of stewardship. Again and again, it was pointed out that Eva Hoffe was unqualified to care for historical documents — especially if some were kept in her own home.

This same argument was thrown around on Spinoza Street by those who wanted to rob Eva of her cats.

I am a cat owner myself and have always loved the way the strays stalk the streets of Tel Aviv. There are those who complain about Tel Aviv’s cat “infestation,” but for me, they stir up a sense of wilderness and mystery. If every street hides a story as interesting as that of Eva Hoffe’s, surely the cats are the keepers of those stories. This is, I believe, as it should be.

On more than one occasion I asked my boss if she ever considered the possibility that Eva’s cats were not mistreated. That they were noisy because they were cats and because cats make noise. After all, we worked at a preschool. Anyone who has ever worked with children knows that, in addition to their charming laughter, they make plenty of noises far less pleasant, often resorting to screaming, yelling and crying. This in no way reflects on the warm and loving environment we provided for those children day after day.

A woman so devoted to cat ownership, I argued, is surely devoted to their upkeep and health as well.

“How can you know for sure?” my boss would ask me.

I didn’t know for sure. Nor did I consider it my place to try and find out.

Some stones are better left unturned.

And so it was that I found myself defending the right of an old woman to be ornery and mad, of cats to live in squalor, and of great works of literature to go lost.

Matthew Schultz is a writer living and working in Tel Aviv.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.