One of the great ironies of Yiddish literature is that many of the stories for which Isaac Bashevis Singer won the Nobel Prize in 1978 first appeared in the pages of the Jewish Daily Forward, one of many Yiddish newspapers that served as the great engines of Americanization of Jewish immigrants. Yet Singer’s fanciful stories ran side by side with daily reports of crime, suicide, scandal and sexual outrage.

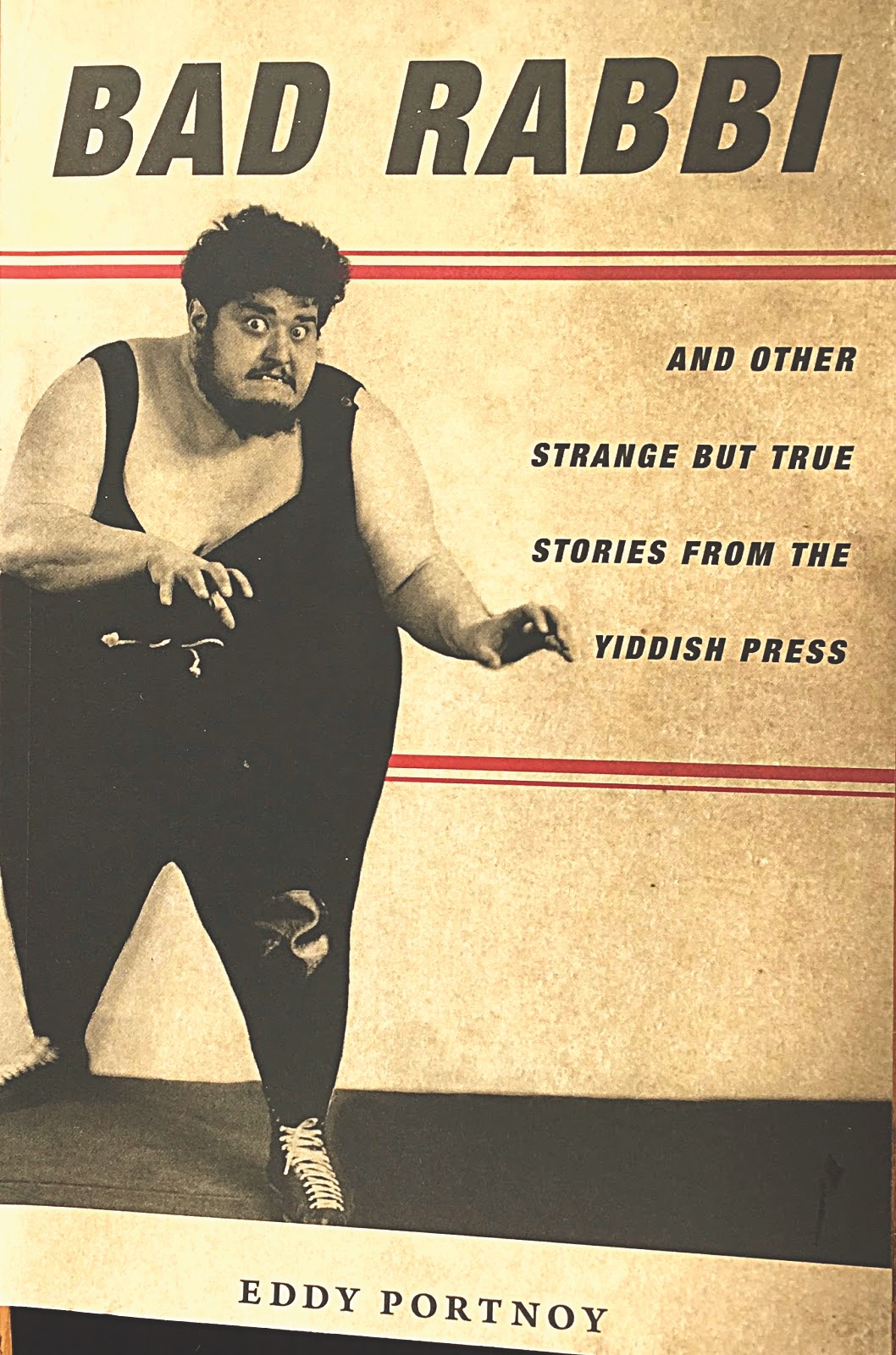

The earthier and weirder aspects of Yiddish journalism are on display in the intriguingly titled, richly illustrated and utterly charming “Bad Rabbi: And Other Strange but True Stories From the Yiddish Press” by Eddy Portnoy (Stanford University Press).

“A chronicle of Planet Jew, the Yiddish press opens a window onto everything one could and could not imagine Yiddish-speaking Jews doing,” Portnoy explains. “Jewish opium addicts? Jewish tattoo artists? Jewish drag queens? They’re all there.”

Significantly, “Bad Rabbi” is the latest title in the Stanford Studies in Jewish History and Culture series, which is edited by David Biale and Sarah Abrevaya Stein, both distinguished scholars. Portnoy is senior researcher and director of exhibitions at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. While “Bad Rabbi” is a decidedly a work of scholarship, it is also — and fittingly — a surprising and sometimes shocking glimpse of the mishegoss that was eagerly reported in the Yiddish press, which Portnoy describes as “one huge, crazed mash-up of an intensively lived Jewish life.”

“The millions of crumbling, yellowed newspaper pages disintegrating in archives and on library shelves contain some of the most bizarre and improbable situations in Jewish history, products of the concrete jungles that migrating Jews fell into during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century,” Portnoy writes. “No similar record of Jewish life appeared before, and nothing like it has appeared since.”

Portnoy drilled down into those archives, mostly in Warsaw and New York, and came up with a treasury of strange but true stories, some of them suitable for a Singer story but others that seem more like pulp fiction. Each story is expertly retold by Portnoy, who also gives us the backstory and thus puts the scandalous details into a cultural and political context.

“The Great ‘Trunk Mystery’ Murder of New York City,” for example, starts with the discovery of the body of a beautiful young woman in a malodorous trunk at the Hudson River train depot in 1871 and ends with lurid revelations of seduction, betrayal, and an abortion gone wrong. Abortion was not illegal at the time, but the abortionist, Dr. Jacob Rosenzweig, was tried and convicted of manslaughter for the accidental death of his patient. The case “opened the floodgates for the anti-abortion crusaders,” and by the time Rosenzweig was granted a new trial, abortion was a crime, a fact that “drove the profession into the back alleys, which resulted in event more accidental deaths.”

“The Great Tonsil Riot of 1906,” as another example, describes how some 50,000 Jewish mothers, “an enraged army of Yiddisha mamas,” poured into the streets of the Lower East Side by rumors that “doctors from the New York City Board of Health were in the schools slashing their children’s throats.” As it happens, a well-meaning school principal had arranged for doctors from Mt. Sinai Hospital to visit P.S. 100 to examine the poor youngsters who would not otherwise be able to see a doctor, and some 83 children were given tonsillectomies. “When the children returned home from school after their procedures, they did so drooling mouthfuls of blood, barely able to speak,” Portnoy reports. The Yiddish newspaper Di varhayt “launched into a tirade about how Irish principals have no respect for Jewish immigrant parents.” But, as Portnoy points out, the whole affair was forgotten by graduation day, when the students “performed scenes from The Merchant of Venice to their Yiddish-speaking parents, none of whom rioted or even panicked.”

‘Bad Rabbi’ is a surprising and sometimes shocking glimpse of the mishegoss that was eagerly reported in the Yiddish press.”

The title story of Portnoy’s book features Shmuel Shapira, known as the Radimner Rebbe, who traveled from Poland to New York in 1923 and found himself accused of fathering a child with the widow of one of his relatives. The woman, whose name was Zlate, claimed that she had aborted the pregnancy and demanded a bribe of $11,000 to keep quiet about it. “The rebbe alleged that after he refused to make any kind of deal with Zlate, she pulled out a revolver and threatened to blow a hole in his Hasidic head if he didn’t agree to step under the chuppah and marry her,” Portnoy writes. But the plot thickens: The rebbe demanded that Zlate pay him a dowry of $16,000 as a condition for marriage, and she consented. And, remarkably, the tale only grows more sordid as Portnoy reveals the astonishing twists and turns of the Bad Rabbi’s downfall. Yet the Yiddish press sided with the rebbe and dismissed Zlate as “a klafte, a crazy bitch,” and “the Friday humor sections were full of Zlate poems, dialogues, and cartoons.”

Portnoy is plainly a disrupter. One of his chapter titles, for example, cannot be printed in a family newspaper, and the photograph on the book cover shows a Coney Island sideshow freak named Martin “the Blimp” Levy, who weighed between 600 and 700 pounds. “Nobody knew exactly how much he weighed because normal scales couldn’t contain him,” notes Portnoy, who also pauses to report that the Blimp was described as “ ‘a seething volcano of sexual passion,’ evidently some kind of Semitic Pantagruel.”

If “Bad Rabbi” is something of a freak show, the book serves a higher purpose. Portnoy points out that “[i]f ordinary people have any familiarity with pre-World War II Eastern Jews, it usually comes from such hypermediated pop culture fantasy phenomena as Fiddler on the Roof, the paintings of Marc Chagall, or perhaps the photographs of Roman Vishniac.” The image that is embodied in these cultural artifacts can be “rich and compelling,” as he writes, “but one that has also become saccharine and glib.” He offers “Bad Rabbi” as a corrective, always strong stuff and sometimes mind-blowing.

Portnoy concedes that he is focusing on “the flotsam and jetsam of Jewish history,” but he convinces us that we learn something important when we contemplate them. “[T]he nitty-gritty of daily life, the quotidian grind, the stories of the criminals and lowlifes, the human detritus that gets washed away and forgotten, the undocumented losers, failures, and freaks who are so common in immigrant neighborhoods of big cities” — all of these unsung heroes are celebrated in the pages of “Bad Rabbi,” a book that took chutzpah to write but is a sheer pleasure to read.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.