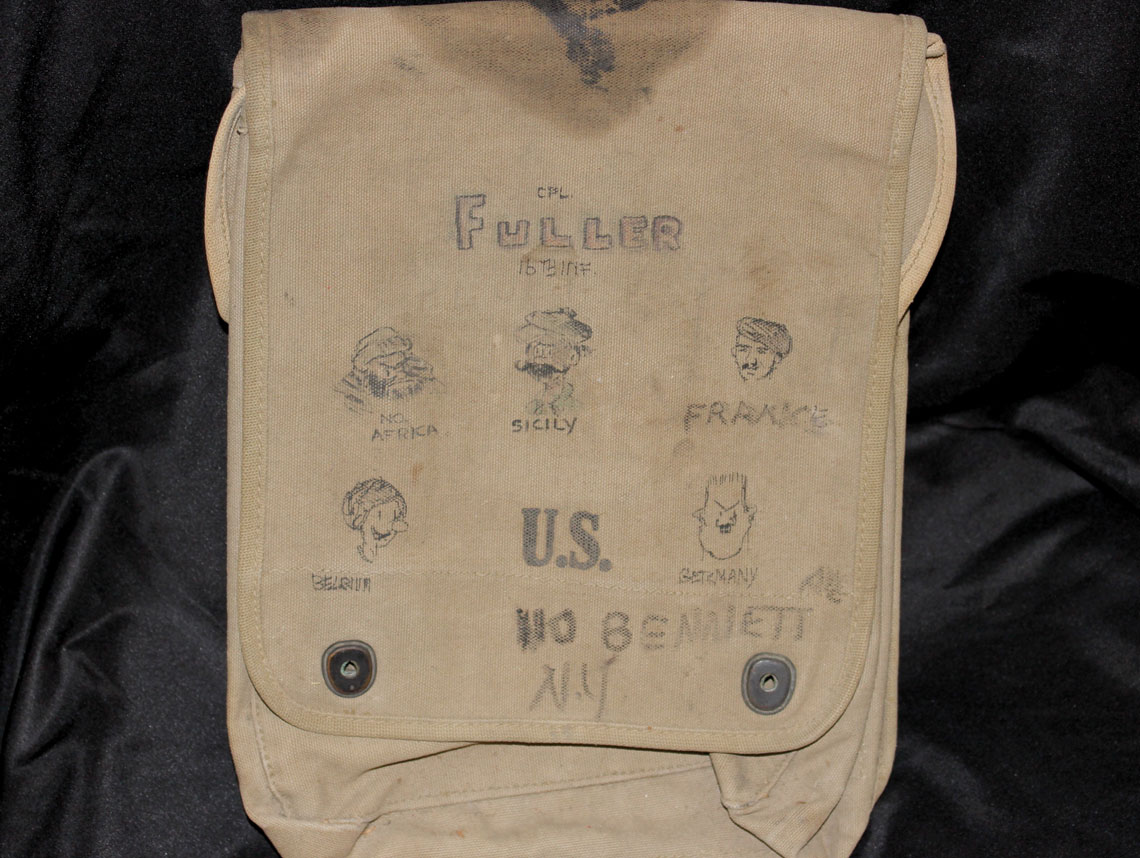

Screenwriter Samuel Fuller’s satchel is part of an exhibition at LAMOTH. Photo by Eric Hall, LAMOTH

Screenwriter Samuel Fuller’s satchel is part of an exhibition at LAMOTH. Photo by Eric Hall, LAMOTH In early 2017, when Beth Kean, executive director of the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust in Pan Pacific Park, was booking a new exhibition, “Filming the Camps: John Ford, Samuel Fuller, George Stevens, from Hollywood to Nuremberg,” she could not have imagined that fresh images of neo-Nazis marching would be in many people’s minds when the exhibition would open on Aug. 27.

But confronting was was thought unimaginable and deciding how to document and report it are major elements of what the exhibition is about. On display through April 30, it all comes together to inform and warn.

Just as we might think white supremacists and neo-Nazis marching couldn’t happen here, Kean wants Angelenos to realize, both through the exhibition and the museum’s permanent collection, that World War II “wasn’t just something that happened halfway across the world. It affected the people of Los Angeles.”

Through film footage and interviews of Hollywood directors Stevens, Ford and Fuller at the time the concentration camps were liberated during World War II, the traveling exhibition, which already has been to several cities, documents the extent of the horror of the concentration camps, which many people had trouble accepting as real once the war ended.

With both imagery and highly descriptive captions written by Ivan Moffat, a British screenwriter who settled in Hollywood after the war, we come to understand, just as those who first viewed these images, the meaning of “genocide” — a word coined in the early 1940s by Raphael Lemkin, a Polish-Jewish lawyer — a deliberate mass murder of peoples by their oppressors.

“Having the exhibit at our museum, which focuses on three directors who made their mark in L.A., who enlisted in the U.S. Army and filmed the liberation of the camps, is very relevant, since it fits our theme of highlighting the Los Angeles narrative,” Kean said.

The exhibition’s curator, Christian Delage, a historian and filmmaker who did much of his research in Los Angeles, also emphasized the local connection. “L.A. is very, very far from Germany and Poland, but they made it there,” he said of the directors.

Stevens, known for directing Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire in Hollywood musicals, was drafted into the Army and assigned to direct the Special Coverage Unit (SPECOU) of the Allied Expeditionary Force. Tasked with gathering evidence of war crimes, the unit was ordered to collect and record information “in a uniform manner and in a form which will be acceptable in military tribunals or courts,” according to the exhibition text.

The exhibition points out that one of Stevens’ major objectives was “to convince Americans of the authenticity of the evidence gathered by his unit.” To that end, the exhibition includes a number of interviews by Stevens with several survivors of Dachau, shot with a camera with synchronous sound.

A film sequence shot by Stevens in Dachau documents, step by step, how the gas chamber operated: A shot of the metal door with the latch on the outside, then the false shower heads, the vent, the gas pipes leading into the chamber and the control panel.

Another sequence at Dachau, shot by Stevens’ crew and edited by him, shows the condition of the camp at liberation, including a train filled with corpses

In 1945, according to the exhibition text, the footage of Dachau taken by Stevens’ crew appeared in a documentary, “Nazi Concentration Camp,” that was used as evidence of Nazi war crimes during the Nuremberg trials.

Stevens and his group also recorded at Dachau a speech given by Rabbi David Max Eichhorn, one of the first rabbis to enter the camp, to a group of survivors and others.

“We know that upon you was centered the venomous hate of power-crazed madmen,” the rabbi said. “In every country where the lamps still burn, Jews and non-Jews alike will expend as much time and energy and money as is needed to make good the pledge which is written in our holy Torah … ‘You shall go out with joy, and be led forth in peace.’ ”

“For me, it was very moving to listen to the speech by the rabbi,” Delage said. “He was pushing them toward life again.”

Ford, who already had won an Academy Award for best director for “The Grapes of Wrath” in 1940, headed the Field Photographic Branch, a special unit of the Office of the Coordinator of Information of the U.S., responsible for producing such films as “December 7th” and “Midway,” for which he won an Academy Award for best documentary. He and his crew filmed the liberation of Dachau. (Ford and Stevens are two of five Hollywood filmmakers featured in the 2014 book and 2017 Netflix documentary, “Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War.”)

Fuller comes into the picture in a different way. A former crime reporter for the tabloid press, he became a scriptwriter. In 1942, he joined the Army’s 1st Infantry Division, which was nicknamed “The Big Red One.” Shooting with a camera he asked his mother to send from home, Fuller, who later would direct such films as “Verboten!” and “The Crimson Kimono,” used it to film the liberation of the Falkenau concentration camp in Czechoslovakia.

The exhibition also features a display of Fuller-related artifacts, made available by Christine Fuller, the director’s widow, and Samantha Fuller, his daughter, who live in Los Angeles. Among them are the camera Fuller used at Falkenau, a canvas satchel on which he doodled, his helmet, the Silver Star he was awarded by Congress and a Red Cross request form that says, “Cigars Please.”

A visitor to the exhibition may wonder after examining the frames documenting the unthinkable: How were these men able to do their work day after day? Ford and Fuller, Delage said, “were soldiers — that helped them to resist the primary emotion. The fact that they were used to the violence of the war helped them to deal with the vision of the camps.”

“For Stevens, it’s a little different” Delage said. “He was coming from a world of musicals and comedies. I think he was really affected.”

In terms of a point of view, Delage believes what you can see in the exhibition is “how they tried to keep a good distance. Not too far or too close.” The directors were trying to gather evidence that would bear scrutiny “and not just to shock people.”

LAMOTH’s Kean, a granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, said she hopes young people, like those she saw in the coverage of the recent events in Charlottesville, Va., take notice of the shocking nature of the exhibition.

“We have a sense of urgency now,” she said.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.