Kalman Aron is a prolific artist. Even during his internment at seven Nazi camps, he didn’t stop drawing — and his artwork saved his life.

“I probably have in Germany a hundred drawings, drawings of soldiers,” the 92-year-old artist said during a recent interview. “They wouldn’t pay me anything, but I would get a piece of bread, something to eat. Without that, I wouldn’t be here.”

Speaking in the living room of his modest Beverly Hills apartment, Aron was surrounded by his artwork, collected over decades. Paintings are stacked five and six deep against each wall, with more in his bedroom and even more in a basement storeroom.

Aron immigrated to Los Angeles in 1949 and built a life, a career and a circle of friends. They were artists and musicians. Now, apart from his wife and a part-time caretaker, it’s his paintings that keep him company.

“I don’t have anybody to talk with,” he said. “All my friends are gone. I had probably 15 friends. They were much older than me. I was the youngest one. And then suddenly, nobody here. I have drawings of them. A lot of drawings in the back there. Filled that room downstairs, filled up completely.”

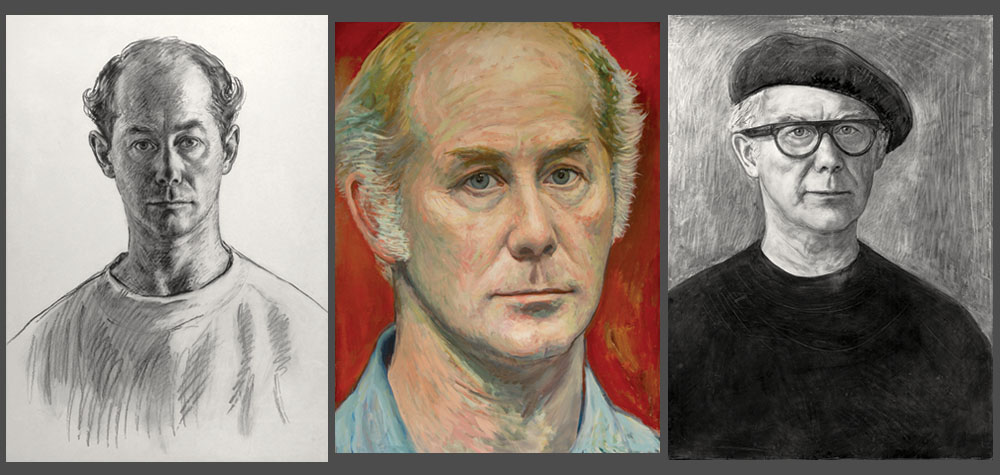

Aron was born with a preternatural talent for portraiture. At 3, he was drawing likenesses of family friends in Riga, Latvia. At 7, he had a one-man show at a local gallery. At 13, he won a commission to paint the prime minister of Latvia. He was 16 years old and a student at Riga’s art academy in 1941 when the Germans occupied the country.

Seven camps, four marriages and nearly 80 years later, he’s proven to be a resourceful and dogged survivor. In the long and circuitous course of his life, art and survival have gone hand in hand.

It began in the ghetto in Riga, when he did a pencil drawing of a guard and showed it to him. The guard liked it enough to spread the word about his talent. The formula repeated itself over and over in the coming years of persecution and hardship.

Still, for a Jew to have writing materials in the camps was considered a risk, so German troops who wanted a likeness would hide him in a locked barrack while he drew them or worked from a photograph to draw their relatives.

“Once I did a portrait and other people liked it, they would do the same thing: lock me in the room, not let me out,” he said.

Aron managed to leverage his skill anywhere he spent a significant amount of time, particularly the Riga ghetto and the labor camps of Poperwahlen in Latvia and Rehmsdorf in Germany. In each place, he attracted a clientele of rank-and-file soldiers and high-ranking officers who rewarded him with scraps of food and pulled him out of hard labor.

What seems like lifetimes later, he believes painting still keeps him alive today.

“Friends of mine, they get old and they don’t know what to do, and they die of boredom,” he said in his dining room, his eyes widening with intensity. “Boredom! And I’ll never die of boredom, as long as I have a piece of paper.”

‘Mother and Child’

Decades before he spoke openly about what he saw during the Holocaust, Aron painted it.

Until 1994, when he was interviewed by the USC Shoah Foundation, he tended not to describe what he had seen. But during those long decades of silence, he produced a number of artworks — in oil, watercolor, pastel and charcoal — depicting his memories of that trying time.

There was Aron at the head of a line of inmates on a forced march. There was Aron at Buchenwald, sleeping outside with a rock for a pillow. There were haggard portraits of fellow inmates.

But the most well-known of these paintings is “Mother and Child,” which now hangs in the lobby of the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust.

Aron moved to Los Angeles in 1949 with a young wife, $4 in his pocket and zero English proficiency after finishing art school in Vienna. In 1951, he had a job illustrating maps in Glendale when one day, he decided to glue two city maps to a board to create an 8-foot-tall canvas.

He brought home the oversized sheet, and after four or five nights of laboring past midnight, he finished a pastel, showing a scene he had witnessed many times in the camps: a mother clutching her child tightly to her face, as if they were one, bound together no matter what abuse they might have to face.

As he worked on the painting, he recalled, “I wasn’t feeling. I saw it happening.”

He went on, “I just said, ‘I’m going to put it on paper.’ I wanted to draw them. That’s why.”

“Mother and Child” sat in his studio for nearly 60 years as he found himself unable to part with it, the glue he used to create the canvas bleeding slowly through the paper to create a brownish tint. Today, it is considered one of his masterpieces.

At the time he painted it, Aron was unable to put his trauma into words. During his later Shoah Foundation interview, as a videographer switched tapes, Aron chatted with the interviewer, a fellow survivor, apparently unaware that audio still was being recorded, and described his difficulty.

“About 30 years ago, I couldn’t do it,” he said. “I couldn’t do it. I would choke up if I did it. I’m fine now.”

Sherri Jacobs, an art therapist outside Kansas City, Mo., told the Journal that art sometimes enables survivors of trauma to express what they otherwise could not. Jacobs has conducted an art therapy workshop at a Jewish retirement home near Kansas City for 15 years, working with many Holocaust survivors. Though they rarely paint explicitly about their Holocaust experience, as Aron has, creative expression nonetheless helps put shape and form to their trauma, she said.

“They can express things in a metaphorical way,” she said, “in a way that it’s leaving their mind, leaving their body and going on paper.”

Painting men and monsters

Drawing in the camps, Aron said he was not thinking of his hatred or fear of his subjects — only of surviving.

In Poperwahlen, for instance, the camp commandant gave Aron a photograph of his parents and ordered him to draw a miniature that could fit in a locket mounted on a ring.

Aron had seen Jews randomly beaten or shot by guards at the camp. More than anything, he was thinking about his own survival as the commandant locked him in a barrack with a pencil and paper.

“I mean, in my head is, ‘Am I going to be alive tomorrow?’ ” Aron said in his apartment nearly eight decades later. “Watching them killing the Jews was terrible, terrible, terrible. I have very bad nights sleeping here.”

The task could have taken him two days, he said. But he stretched it over more than a week for the exemption it afforded him from back-breaking labor.

It’s difficult for Aron to estimate how many portraits he drew. He knew only that the same interaction repeated itself many times with Nazi troops.

“Wherever I was, I made sure I had a piece of paper and pencil,” he said.

As the months passed, he parlayed his skill into gaining more materials, piecing together a sheaf of drawings that he carried with him. Observing his assured manner and his materials, camp guards mostly left him alone.

“When they saw that, they knew, ‘Don’t touch this guy, he’s doing something for us,’ ” he said.

By the end of the war, his skill accounted for perhaps an extra 5 pounds on his skeletal frame, he told the Shoah Foundation interviewer — a small but critical difference.

“There also were people that were tailors and shoemakers,” he said in 1994. “They would also get fed much better. They were indoors. They would sew, you know. These are the kind of people that had more of a chance of survival than a guy who was digging ditches.”

Reclaiming a world of light and color

Jacobs, the art therapist, said understanding Holocaust survivors as the product of a single experience can be misleading, traumatic though it may have been. And in trying to understand Aron through his art, putting the Holocaust constantly front and center would indeed be a mistake.

Of the hundreds of paintings that line his apartment, relatively few deal with the Holocaust. More often, they are landscapes of the places he’s visited, views from his balcony looking out at downtown L.A. and portraits of the women he’s loved. Prominently displayed is a 2006 oil portrait of Miriam Sandoval Aron, his fourth and current wife, straight-backed, wearing a baseball cap during their honeymoon in Hawaii.

His earliest landscapes in Los Angeles are often devoid of color: A rambling house in Bunker Hill is rendered in shades of gray with no sign of life; a monochromatic landscape of Silver Lake shows not a single inhabitant. But soon enough, he took to painting colorful tableaus of the city at various times of day.

Eventually, he made enough money to rent a West Hollywood studio with high ceilings and northern light, where he hosted parties that lasted until sunrise. Over the years, his art has been exhibited at several museums and galleries, including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Los Angeles Art Association and the Seattle Art Museum. He has painted a number of celebrities and public figures, including novelist Henry Miller, pianist and composer André Previn and then-Gov. Ronald Reagan of California.

For months at a time, he traveled through North America and Western Europe — though never to Germany — stopping whenever he was moved to paint.

His third wife, Tanis Furst, described one such incident to author Susan Beilby Magee for “Into the Light: The Healing Light of Kalman Aron” (2012), a book of Aron’s art, framed by interviews with the artist.

In 1969, driving through Montreal during a trip across Canada, Aron pulled over in a rundown part of town to paint a house where a woman lived with dozens of cats.

“This happened all the time on this trip,” Furst said. “He would drive along and stop: ‘Gotta paint that.’ We had a lot of fun.”

A short while later, Aron’s only son David was born.

“I was a very happy guy when my son was born,” he says in the book. “In fact, it was the happiest day of my life.”

Telling his story

Even in 2003, when Magee first set out to write “Into the Light,” she said she found Aron profoundly ambivalent about telling his story of sorrow and survival.

In an interview with the Journal, Magee said that while part of Aron seemed to be saying “It’s time to tell, the pain of not remembering is greater than the pain of remembering;” another voice was telling him “You survived because you were invisible; do not tell your story; do not be seen; to be seen is to be killed.”

Magee had spent more than a decade in Washington, D.C., working in government, before quitting in the late 1980s to pursue hypnotherapy, meditation and energy healing. One thing she was not was a writer.

But that didn’t deter Aron. Sitting down for lunch in Palm Springs in 2003 with Magee and her mother, one of his earliest and most ardent patrons, he suddenly fixed upon Magee with his blue-eyed gaze.

“Completely out of the blue,” she recalled, “he turns to me and says, ‘Susan, will you write my story?’ He is a highly intuitive man, and somehow he knew he could trust me to do it.”

Although he had produced numerous paintings dealing with the Holocaust, he had been hesitant to speak about it, even with those closest to him.

“Kalman shared some things about his family and the Holocaust, but not in a great deal of detail,” Furst says in the book.

Nonetheless, after his 2003 encounter with Magee, he consented to 18 hours of interviews with her. Later, she traveled to Europe to retrace his steps. Nine years after she set out, the book was published, with a release party at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles.

Recently, Aron agreed to be featured in an upcoming documentary about his life and art, backed by television producer Norman Lear.

“We’re going for the Oscar on this thing, and you can quote me on that,” said Edward Lozzi, Aron’s longtime publicist who introduced him to the documentary’s director and executive producer, Steven C. Barber.

Aron said he hopes the extra publicity will help him sell paintings and pay rent, which even at his advanced age continues to be a concern. But in general, he’s content to sit at home and paint.

Though Aron sometimes struggles to remember words and names, he remains spirited enough, painting for hours each day and eagerly engaging visitors in conversation. “I can manage six languages,” he said. “But I can’t remember people’s names.”

Magee said she believes that through telling his story, Aron has at long last found peace.

“His willingness to tell his story — to finally remember after suppressing it all those years — gave him that freedom to paint for the joy of it,” Magee said.

These days, his paintings are mainly non-objective rather than representative.

“I used to go to the park,” he said, sitting in an airy corner of his apartment, next to the kitchen, where he keeps his home studio. “I used to meet people. Now, I’m not allowed to drive at my age. So I’m here all the time.”

Lacking subjects for portraiture, Aron paints sheet after sheet of shapes and colors.

“I enjoy the design, the design,” he said, holding up a recent painting, a set of undulating neon waves. “Movement, movement. This moves, it doesn’t stay still.”

Aron considers himself lucky to have a gift and a passion that keeps him occupied into his old age.

“My situation may be a little bit better than some people who came out of the camps,” he told Magee during their interviews. “They may have nothing else to do but watch television and think about those bad days in the camps. I did that in the beginning, but I got away from thinking about it by doing portraits, landscapes, traveling and painting. I think that kept me away from all this agony of ‘How did I survive?’ or ‘Why did I survive?’

“I did, and that’s it.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.