Perhaps you really don’t wish that sinners be struck down by God? Perhaps you don’t believe that God is male (and that even when this language reduction isn’t interpreted literally it is harmful today) since reinforcing patriarchal structures so deeply is dangerous? Perhaps you don’t wish to turn back the clock to previous eras? Perhaps you don’t wish that God limits human free will and intervenes with nature consistently when you pray for daily Divine interventions? Perhaps you think it is wrong that healing prayers be reserved just for Jews or that prayers for peace be Judeo-centric? Perhaps you feel that the grand universalistic visions and utopic ideals of Jewish tradition have not been fully realized in the more limited pre-modern articulation that we’ve inherited? Perhaps you believe in evolution and modern science? Perhaps you don’t believe that abandoning democracy and returning to a political monarchy, transitioning back from a rabbinic intellectual tradition to a priestly tradition, and building a Third Temple with mass animal sacrifices is God’s highest aspiration for the future? Perhaps you look at Jerusalem today and don’t see desolate destruction? Perhaps you feel the most ideal prayers (which often seem absent from the liturgy) should be about eradicating injustice, hate, and oppression and replete with expanding love, respect, and tolerance? Perhaps the words of prayer themselves feel so strained that they alienate you from God more than draw you closer (even after the reading the most compelling commentaries on them)? Perhaps they don’t deepen your deepest moral intuitions and expand your spiritual imagination?

Too often, I’ve heard that there are some parts of the traditional liturgy that many do not believe adequately reflect the highest moral truth – that these words don’t seem to be fully in accord with the highest Jewish values as generally understood. They pray that they are yearning for something that they do not actually crave. Yet they still feel committed to reciting these traditional words of prayer, albeit with a new, uniquely relevant, holy, and moral intention at times or at times just in confusion but guarding the tradition and yearning for God’s higher intention. It seems as though reciting false, or expired, words with the highest intentions, rooted in the spirituality of our ancestors, may reach higher heavens than erasing them in favor of new words that feel right in the moment. But here I will argue that we should acknowledge the imperfection of our prayers to God.

For those who are very comfortable changing the traditional liturgy whenever desired, my argument here will likely sound absurd. After all, if I don’t fully believe a prayer then I either shouldn’t say it or I should just change it, right? My argument here will also likely sound absurd to those who fully submit (intellectually, spiritually, & emotionally) to the literal interpretation of the traditional liturgy the Jewish people have inherited as being flawless and perfect for all eras and contexts. Isn’t it arrogant to think we know better? But if you are like me and feel committed to traditional prayer but also feel that merely shifting your intention to reinterpret prayers is no longer enough, then please read on.

I’m suggesting that we might declare to God, with full humility, integrity, & courage, that we don’t actually want certain things that we ask for on a daily basis even though we honor the holy tradition of our revered ancestors and the halakhic process by continuing to say them.

Perhaps, it is not enough to merely shift our intention, but we must actually acknowledge verbally that there are some flaws in what we’re saying. So below, I propose a tefillah that I recommend we recite before prayer. I share this with trepidation. Yet I have even more trepidation about not exploring this and not acknowledging the truth of our hearts before our Creator, Who holds infinite wisdom & endless compassion, Who indeed already knows our every thought and feeling. We wish to acknowledge and embrace the fragmentation of broken lower earthly truths in order to except the harmonious wholeness of the highest heavenly truths. As Rav Kook taught: “In relation to the highest Divine truth, there is no difference between formulated religion and heresy. Neither of them yields the truth, for every positive human assertion is lacking before the divine Truth,” (Arpelei Torah 45). The religious person must acknowledge the imperfection of our articulations, the limitations of our language (even holy language!). The depths of our hearts and souls , on the other hand, reveal something much deeper: “If we encounter thoughts which seem to us defective or empty, their defect or emptiness is only in their outer expression,” (Orot HaKodesh I, 17-18). In Rav Kook’s poem “Expanses, Expanses,” he concludes: תנה לי שפה וניב שפתים אספר במקהלות אמתי אמתך ,אלהי “I shall declare before the multitudes my fragments of Your truth, O my God.” We are love sick to connect with God, clinging to the holy Torah, and yearning for the most cherished religious ethics and the most sublime truths. Because of this love for God, we only seek words and actions that will bring us closer.

The Prophets were more radical and they changed traditional liturgy so that they would not feel they were lying to God by calling God “awesome” and “mighty” when God did not appear awesome & mighty to them (Yoma 69b):

אתא ירמיה ואמר נכרים מקרקרין בהיכלו איה נוראותיו לא אמר נורא אתא דניאל אמר נכרים משתעבדים בבניו איה גבורותיו לא אמר גבור

But we are not prophets! Yet in the spirit of the prophets who took the integrity of their words of prayer very seriously, we too must hold ourselves responsible to the truth of our prayers. There is a holiness to embracing the religious skepticism that prevents us from falling into absolutist binary thinking (either that the prayers are perfectly good/true or that they are completely bad/false). To me, being religious means to be full of wonder, amazement, questioning, and doubt, not, God forbid, bracketing our Divine gift of our Conscience to submit to the arrogance of certainty. Might God laugh at the one who prays with certainty that they know the will of God? That they are certain that it is their exact words that are the key to unlocking the gates of heaven? That they silence the voice emanating from their inner Godliness in favor of social conformity? That we blindly submit to truths of the past while silencing newly revealed truths? Rather, we yearn for God, we cleave to the Torah, we seek the truth. We hold on to the tradition but acknowledge that we are limited & our prayers are insufficient. We recite the traditional liturgy while also seeking to spiritually transcend the words invoked to reach new heights.

For those like me that are fully committed to halakhah & feel spiritually connected to the holy yearning of our ancestors yet also are committed to pursuing their own unique spiritual integrity, let me know how adding this tefillah goes for you if you try it. Or if you write your own tefillah, I’d love to learn from it. I don’t believe this prayer addition removes our responsibility to work to affirm the words that literally represent the highest Torah ideals we know to be true and beautiful (and to work to understand metaphors and hints with hidden meaning more deeply) nor does this prayer addition exempt us from working hard to re-interpret those words that beg for higher understanding and interpretation, but this does express a humility (or perhaps a גאוה דקדושה) before God that we ourselves do not know the truth and our humble insecurity that our words are fully adequate to be accepted as they stand.

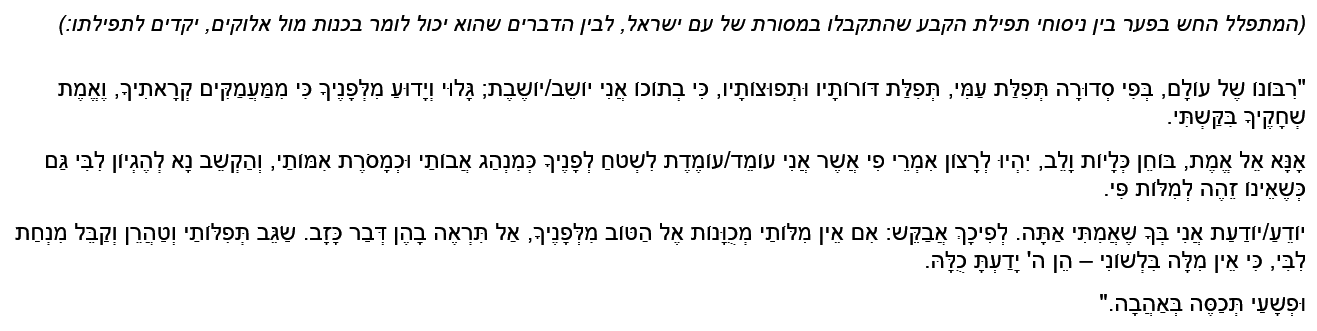

Here is the new tefillah addition (followed by a translation):

(The worshipper who perceives a gap between the wording of the official prayers that have been accepted as Jewish tradition, and what he/she can sincerely utter before God, should prefix this prayer:)

Master of the Universe, I approach You with the prayers of my nation prepared in my mouth, for I dwell among my people; You know well, that while I call out to You from earthly depths, it is in fact the truth of the Heavens that I pursue.

Please, Lord of Truth, Who intimately fathoms our inner world, may the utterances of my mouth which I pour before You, in conformity with the custom of my forefathers and the tradition of my foremothers, be agreeable to You, but please also heed the meditations of my heart, when they are not identical to the words of my mouth.

I know that You are authentic, and consequently I appeal: If my words are not coordinated with Your absolute goodness, don’t consider them as deceitfulness. Exalt my prayers and purify them, and accept the offering of my heart, for “Even before a word is on my tongue, You, Lord, know it completely,” and conceal my failings with love.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.